Not Time to Relax, but Not Time to Panic, Either

As the situation in Ukraine continues to deteriorate, extremist views of both Russia and the United States are given far too much credence and media space. An examination of history and context, sorely needed in this situation, will reveal that, while certainly Russo-American relations are taking a big hit, and while this is certainly the worst Russo-American crisis since the Cold War, things are not as bad as many would claim. That is not to suggest that this is some even-handed, neutral situation, but only with a clear view and understanding of what is really going on, minus the noise, hysteria, and falsehoods perpetuating discussion of this issue, can a better path forward come to light. Rather than be so at odds, the U.S. and Russia can and should become allies.

Republished on LinkedIn Pulse March 3, 2015

This was originally posted by the Russian International Affairs Council, and was “Post of the Month” for February/March 2015.

By Brian E. Frydenborg- LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter (you can follow me there at @bfry1981) February 26th, 2015 (updated February 27th-28th)

One of the sad things about looking at current commentary about Russia, America, and the state of their relationship is the lack of measured and reasoned commentary. Make no mistake, though, the problems between Russia and America are serious and affect a whole host of major issues around the world from wars in Syria and Ukraine to global energy distribution, access, and prices, to space exploration and militarization, just to name a few.

Perhaps this is understandable, given the nature of the history of the most serious, dangerous rivalry the world has ever seen. Sparta and Athens, Greece and Persia, Rome and Carthage, England and Spain, England/Britain and France, Britain and France vs. Germany, Japan and China/Korea all pale in comparison in terms of the threat presented to world with the technology that enabled both the U.S. and Russia to be able to project nuclear destruction anywhere on earth and to the entire earth, especially when that technology was matched with red-hot ideological incompatibility and serious conflicts of interest all around the globe that often made the so-called Cold War burst into quite hot conventional proxy wars (and not always proxy even if this was unknown publicly at the time). The world came far too close to nuclear war and possibly the destruction of humanity because of this rivalry.

Thus, there is an understandable natural tendency for each to view the other as larger-than-life, inflated, and in hyperbolic and exaggerated terms. It has been remarked by more than a few that truth is among a conflict’s first casualties, but among rivals, you could add objectivity and a sense of proportion to that initial casualty list.

Among certain not uncommon elements in the U.S. and the West, especially among American Republicans, there is a tendency to speak of Russia and Putin today hyperbolically in the same breath as interwar Germany and Hitler, that somehow, Putin is a monster of a potential Hitleresque quality, if not in genocidal intent then in a global ambition to dominate. The word “appeasement” is thrown about as something to avoid when it comes to Russia. Putin is the greatest threat to the world order in decades, and, in this view, must be stopped.

Meanwhile, an incredibly common view in Russia and certainly among Putin’s ruling elite is that the U.S. is a global menace that is responsible for the rise of global terrorism and seeks to encircle and weaken Russia through imperialism while empowering Russia’s longtime enemies on Russia’s own borders. Everything can be explained by a U.S. government and (anti-Russian) mainstream media global conspiracy to bring about corporate imperialism not just to Russia, but the whole planet. It’s about global domination, and Russia is under siege!

In truth, neither view captures the real policy aims and legitimate concerns and interests of either party.

The View from Russia

Russia’s actions, through a casual glance, may seem like those of a power hell-bent on wrecking the world system and bent on global domination. But this ignores much history, both from long ago and in recent decades. Russia, for one thing, has a deep insecurity and paranoia in its culture that goes deep into its history, beginning from when what is now Russia was devastated by Mongol invasions and domination. Russian history for the next 800 years is not a happy tale, with both some of the worst invasions suffered in the history of the world (Napoleon in 1812, German assaults in WWI and WWII) and some of the worst and most brutal rulers of any major state, from Ivan “the Terrible” to Stalin. Fear, then, is something that must be given its due in trying to understand the Russian psyche. While I would not say that Russians are truly afraid of the U.S., they do fear being weak and fear what that could mean, given their history. And the late 1980s and 1990s were a time when Russia was very weak, taken advantage of by Western missionaries of capitalism and fighting losing wars in Afghanistan and Chechnya. This was combined with Russia seeing its Soviet Empire collapse abroad while suffering crushing poverty and instability at home. A lack of security both at home and abroad, then, permeated the Russian mind in this period, and the Soviet system gave way to the Russian mafia, oligarchs, and anarchy.

It was into this chaos Vladimir Putin waded, got his hands dirty, and stabilized Russia at home, though at the cost of moving firmly away from democratic norms. But for Russians, the rest of the world was another matter, and still a scary place and source of great anxiety. The worst terrorist attacks in the Western world (if you include Russia) over the last 15 years, excepting 9/11, all took place in Russia in spectacular fashion, from several 1999 bombings of apartment complexes (where there are actually some serious questions as to whether the Russian government staged them, and the war launched in response to them set the stage for Putin’s rise), to assaulting an opera house during a performance in 2002, to attacking a grade school full of children in 2004, in addition to other smaller attacks. Islamists from the Caucasus were the perpetrators of many of these attacks, and al-Qaeda had (and now even ISIS has) some connections to these people. Putin himself very much rose to power on prosecuting a war the Second Chechen War (1999-2009) there in response to terrorism, and brutally so. It should be no surprise, then, that Russia also sought to flex its muscle further south into the Caucasus in Georgia in 2008.

But, even with aggression in Ukraine, rather than see this as a nation hell-bent on world domination, we should see a wounded animal, carving out the territory covering the approaches to its cave, with the memory of much pain coming from the places against which it lashes out. Apart from Islamic terrorism coming up from the Caucuses, there are still some alive who remember the Nazi assault that very much came through the plains of Ukraine. It is not a mistake that Putin chose to highlight a real but tiny fringe neo-Nazi movement that forms a significant part of Svoboda, one small, far-right Ukrainian political party, when he was framing Russian involvement there. These are very real fears among Russians even if the threat—a Nazi Ukraine engaging in mass killing of its ethnic Russians or invading Russia—is not something that Russians should be concerned about as anything likely to happen anytime in the foreseeable future. The idea that a neo-Nazi fraction of a minor party or two in Ukraine (the larger of which only won its first seats in 2012 and lost almost all of those in October 2014 parliamentary elections) is somehow a justification for Russian support for rebels in an internal Ukrainian civil war or for annexing or invading sovereign Ukrainian territory is, simply put, flat-out ludicrous no matter how often and how strongly Putin and his machine of Russian-government-controlled/funded media outlets (most notably the very slick RT.com) choose to hype up their threat-level and make false claims that the West is ignoring these extremist elements. Still, it is important to note the emotional, very powerful themes going back to WWII—what Russians refer to as “The Great Patriotic War” and a war filled with nationalist, Soviet communist, and Nazi fascist overtones—that are still major motivators and influencers for Russian action today.

But there is a sizable minority of ethnic Russians in Ukraine in which the Kremlin has a legitimate interest, and we must also remember that the border is a very modern thing: it only dates to around end of WWI, a time when Russia was very weak, having suffered greatly during WWI and then in the middle of a revolution and a civil war (in which American Western forces intervened against the communist Bolsheviks). And when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, a Russian Bolshevik who had spent much of his early life in Ukraine and had risen through the ranks of Ukraine’s Communist Party apparatus, symbolically “gifted” the Crimea to Ukraine in 1954, this was at a time when Russia and Ukraine were inseparable and when this was going to be the situation as far forward as anyone could see at the time. This “gifting” of Crimea to Ukraine was done to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the joining of Ukraine and Russia, and a poster created for the occasion shows a Russian and a Ukrainian holding a single shield with the caption “Eternally Together” (see below). The gifting also symbolically fit into Khrushchev’s general “de-Stalinization” program. Historically, Russia had put a ton of resources and effort into developing the Crimea over the past few centuries, and the idea that this would be or today is part of an independent Ukraine is not only not something that did and does not sit well with Russians, but is something that did not have much historical weigh to back it up. The last time a Ukrainian state had control/influence over Crimea was about 800 years ago, but the Kievan Rus’ state lost control to Mongol invaders before it was itself destroyed by the same attackers. It is also important to note that there are well over twice as many ethnic Russians in Crimea as there are ethnic Ukrainians.

So Russia had, in many ways, legitimate claims, interests, and aspiration in Ukraine. But these do not create a license for doing what Russia has done, and this will be discussed later.

A View from a Divided Ukraine

Russian policies towards Eastern Europeans, including Ukrainians, from Czarist times had been oppressive (as they were for ordinary Russians, too), so that the many peoples who were able to form their own states after WWI were only too happy to do so. Several Ukrainian postwar states emerged after the war, but chaos and conflict prevailed and they survived only briefly as independent states before falling under the control of the new Soviet Russian state; thus, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic became a founding republic of the Russian-dominated Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Under Stalin in particular, Ukrainians were treated brutally and even famine was used as a political weapon, killing millions of Ukrainians and possibly fitting the legal definition of genocide (there is even an active Russophile movement that denies these very real horrors that would even put the climate change denial industry to shame). Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that many Ukrainians welcomed the Nazi invasion in 1941 and supported, even fought enthusiastically, for Germany against the forces of the Soviet Union. Even today, the divided loyalties from the World War eras are a highly contentious issue between Ukrainians of various persuasions and especially between the ethnic Ukrainian Ukrainians and Ukraine’s sizable ethnic Russian minority, concentrated in Crimea and Ukraine’s east, as well as between Russian and Ukraine governments. Now, with fighting erupting into civil war between Ukrainians and into fighting between Ukrainians and Russians, echoes of these past conflicts are playing out hauntingly in this new one.

The View from the U.S. and the West, and the Cold War

Americans, especially, love to help people with freedom (our rate of success in these endeavors, though, may not match our enthusiasm). While there are often other reasons America enters into wars, the idea of fighting for freedom is certainly a factor, especially in the mind of the public. Our own Civil War may not have begun as a crusade to exterminate slavery on American soil, but it evolved into that cause with wide public support. People liked the idea of freeing Spain’s colonial subjects from Spanish ruleduring the Spanish-American War. At the end of WWI, Woodrow Wilson tried—and failed—to push for self-determination for many of the dominated and colonized people of the world. FDR tried also, and it is largely because of him that the United Nations exists today, but he died before WWII ended and the Cold War would derail much of what he had hoped the UN would become. Still, for all its shortcomings, it would be hard to argue that any other single entity does more to promote human rights, advocate for peace, and assist the poor and helpless of the world more than the UN.

As for the Cold War, most Americans thought they were fighting to keep the world safe from the threat of Stalinist-style Soviet oppression. There is absolutely no question about whether Soviet and Soviet-backed regimes were repressive or often brutal. The problem, which even as an American I can admit, was that it was easy for American policymakers to mistake less harmful governments and leaders—Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, Muhammad Mossadegh in Iran, even, arguably, Fidel Castro in Cuba and Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam—for being more dangerous than they were. Or, to put it another way, the U.S. lost sight of defending freedom for people to choose by conceiving of freedom as being free from communism, a narrow and myopic view that led to horrible abuses, tragic and unnecessary wars, tremendous loss of life, and America supporting regimes and leaders that did anything and everything to oppress people and deny them freedom. If they were not communist, that was usually good enough for us. In fact, our policies were so bad in this era, and led to so many of the world’s current problems, that I am convinced that the U.S. did more harm than good in the period after the post-WWII Marshall Plan and the occupation of Japan up until the fall of the USSR.

I would also argue that American concerns about Communism—which were often though hardly always justified—do not justify our Cold War misdeeds. Conversely, that the U.S. often aided the forces of imperialism and dictatorship does not change the abuses and murderous nature of Russia’s Joseph Stalin, China’s Mao Zedong, Cambodia’s Pol-Pot, their regimes, and other communist entities. One side’s misdeeds cannot justify the misdeeds of the others, and ultimately, both the USSR and the USA were responsible for their government’s action and responsible for the support they provided to abusive regimes, whatever the ideology behind them. Still, it must be remembered that, like the Soviet Union, the U.S. felt threatened by its ideological nemesis’ agenda and, also like the Soviet Union, fear and security more often than not motivated its questionable decisions (in fact, even among large and powerful states, fear of being attacked or weakened to a point that invites future attack is often a prime motivator for aggression, even going back to ancient Rome). Both countries had suffered surprise attacks from major enemies in 1941—Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack and Germany’s Operation Barbarossa—that scarred their nations’ psyches, so that both their publics and leaders were determined to project strength rather than be caught unprepared again. Again, this does not justify either America’s or the USSR’s crimes, but it is important to understand and respect these motivators rather than simply ascribe greedy world-domination to either party in a banal and facile manner.

Fall of the USSR, Expansion of NATO: Russia and America Become Lovers but It’s a Messy, Short-Lived Affair

When the Cold War finally ended, it was not only a great moment heralding less conflict (objectively a true statement) for not only the U.S. and Western Europe, but also Russia, Eastern Europe, and the world, despite Putin’s thoughts to the contrary. Celebrations were common all over states that had unwillingly been dominated and controlled by the USSR. Contrary to popular opinion among Republicans, Ronald Reagan did not “win” the Cold War: the Soviet system’s own inadequacies had doomed it to collapse from within decades ago. And yet, the system did not suffer any marked decline in the years preceding the dissolution of the USSR. Rather, people had been wanting change for years and wanted the whole system to be swept away. This was what Russians, Poles, Czechs, and others wanted, and not because of American propaganda. When Gorbachev filled people’s hearts and minds with the idea of reform, it was also an admission that Soviet leaders knew the system had failed, and the people took their newly-granted freedoms and created a revolution, all the way from Vladivostok to Berlin, and they did not hesitate to abandon the Soviet model. Soviet communism had reduced dignity to a slogan and destroyed it as a reality, and only a wholly new system would satisfy their most human of needs. In short, the Cold War ended because the system had failed to provide the people of the Soviet Union satisfaction and hope for decades, and even the leaders did not believe their system was worth fighting for anymore, let alone repressing and killing large numbers of people who had no faith in the system. Russians wanted freedom from their system, and others wanted freedom from Russia.

Between the U.S. and Russia, in the end, there was not so much animosity as relief and a desire to put aside differences and work together. America and the USSR had joined together to defeat Nazi Germany and eradicate smallpox from nature. Now, a weak and failing Eastern Europe and Russia needed help, and Americans and their leaders genuinely wanted to be there for them. Presidents Yeltsin and Clinton developed a genuine friendship filled with affection. Voluntary, grassroots protests demanded revolution not just in Russia, but throughout most of the states that had been under Soviet control or influence; this was no imposition from abroad, no imperialist design. And transitions always have the potential to be messy, anytime and anywhere. In this vein, unfortunately, some of the people—both Russian and non-Russian, including some Americans—leading and aiding in this massive, historic transition to a democratic market system were incompetent and/or not well-intentioned; in other cases, the challenges and power vacuum were too great for there not to be problems. These varied and complicated causes helped to bring about a decade of instability and weakness—especially economic weakness—in Russia, a decade that seriously derailed Russia’s progress towards developing healthy democratic and economic institutions. Volatility, hardship, illegality, massiveand widespread corruption, and the dominance of oligarchs and the Russia mafia was the norm. Some of these trends continue even today. It was out of this terrible decade from which Putin emerged to lead a Russia moving away from democracy, human rights, and democratic norms and awayfrom enthusiasm for democracy. This was largely under Putin’s direction and according to his will, but often with the backing of the Russian public. Over time, these undemocratic trends have only intensified.

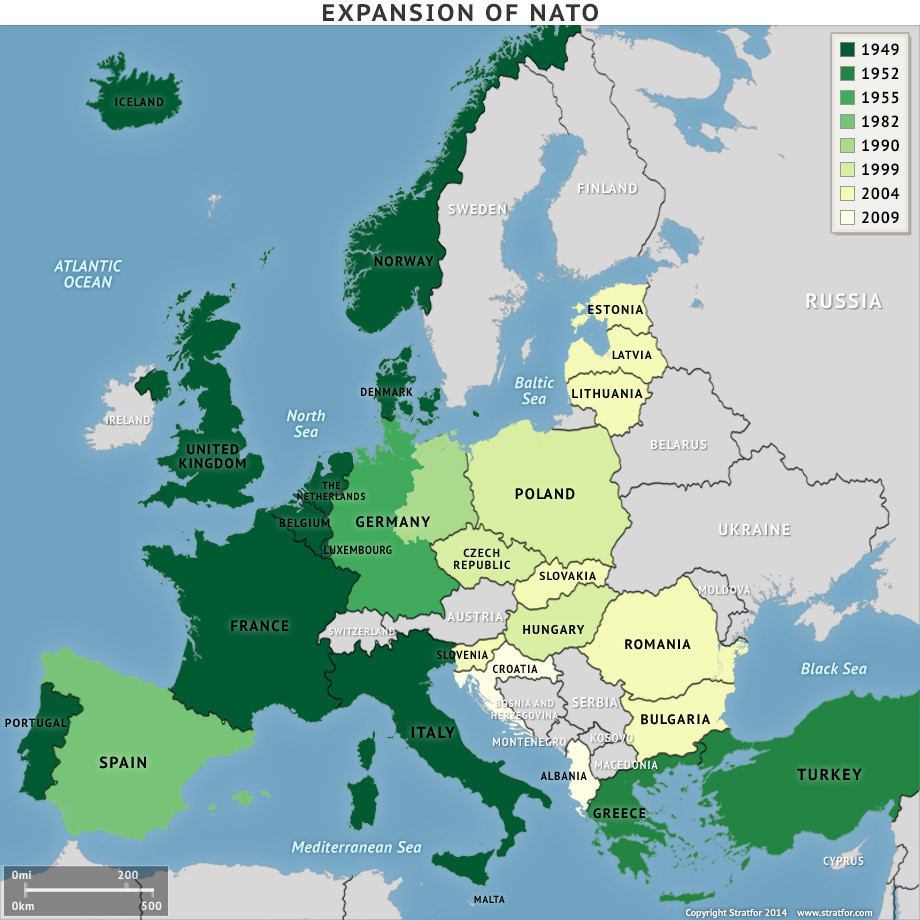

Outside of Russia, most of the people that had lived under Soviet control or dominance were eager to put the past behind them and move toward more democratic, market-based societies as well. From Central Asia to the Caucasus, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from Budapest to Kiev, new democracies emerged that were eager for U.S. patronage and support, military alliances and protection. This desire on the part these people would become one of the biggest issues of contention between Russia and the U.S. Russia, still emerging from a Cold War mentality, was naturally wary of NATO—the U.S./European military alliance—expanding eastwards into formerly Soviet territory. George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of State, James Baker, did suggest to Gorbachev in 1990 that, allowing a newly unified Germany—including Soviet-controlled East Germany—to remain in NATO could result in NATO deciding to “not shift one inch eastward.” But these were just proposals at the time, and Baker’s proposal could have meant for that year or a few years. But there was certainly no formal agreement. It seems, if anything, a series of honest misunderstandings, during what were mostly informal discussions in 1990, led to Russia’s believing that there would forever be no NATO expansion eastward. In particular, German officials gave stronger private assurances but were not speaking for America or NATO at the time. Perhaps there could have been more clarity, but Russia has stubbornly clung to a myth of Western lying and betrayal on NATO expansion. Even some on the then-Soviet side later disputed that there was an agreement, including Gorbachev himself in an interview late in 2014. Gorbachev, while feeling that years later the U.S. later acted in “violation of

The Big Picture and the Way Forward

Considering all of this, it is more than safe to say that Russia and the U.S. have drifted away from their honeymoon of the early 1990s and that that the love is gone. Now, there is only a period of new hostility. If anything, the last twenty-five years were an interregnum between cold wars, but this one should not be nearly as bad, as we will see.

There are few rational reasons why Russia should behave in such a hostile way to the West, define its interests as contrary to the West, and feel the need to oppose to West so often. It almost seems at times as if Russia wants to define its role as simply an anti-American standard bearer. Russia has been on the wrong side of just about everything in recent years. Yes, Russia was right in opposing us on Iraq (2003), and that’s about it. It was wrong to support Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia, wrong to oppose NATO intervention designed to stop a civil war in Libya (where Libya could have turned into Syria), wrong to support Assad in Syria (I will say that, while Putin is overall wrong on the Syria issue, he and Russia deserve no small amount of credit for the Syria chemical weapons deal. While it is important to remember that all signs point to Putin and Russia not doing anything on this issue without the threat of American military strikes against Assad’s regime, with Putin’s proposal coming only at the 11th hour, removing large amounts of WMD from Assad’s hand is objectively a good thing, as well as also being the most productive act in the international arena for Putin and Russia in recent memory. But as I have written before, this deal on Syria’s chemical weapons did nothing to stem the drivers of the conflict, bring the war in Syria any closer to ending, and was, if anything, an insurance policy for Russia to keep its client regime in power in Syria. And seriously, can anyone read Putin’s famous op-ed in The New York Times warning against American military intervention in Syria with a straight face? Just thinking of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine today while reading makes it hard to not laugh out loud at the sheer chutzpah and hypocrisy). When you’re on the side of Milosevic, Qaddafi, and Assad while they are all committing mass murder against civilians, you know you’ve got a problem. The U.S. supported some pretty murderous regimes in the past, but not since the end of the cold war with any kind of robust support. Yes, the Saudi Arabian government is terrible, and oppressive, but they’re not killing their own civilians by the thousands.

Russia is also wrong to fear NATO expansion.

If anything, as the West and its new Eastern European allies considered how to proceed after the end of the Cold War, NATO expansion can be said to have moved forward cautiously, happening only in stages five to ten years apart, and one of the few major reasons why this would have proceeded so slowly and cautiously is out of respect for Russia’s concerns. And NATO even put the brakes on both Georgia’s and Ukraine’s earlier attempts to join the alliance, in no small part because of Russia’s concerns (though that does not rule out admission in the future). So the idea that somehow NATO ignored Russia and Russian concerns is groundless.

Still, it not hard to understand why Russia would be uncomfortable, even fearful, of the fact that so much of its former empire has joined and is clamoring to join a U.S. dominated military alliance. Concerned mainly with cementing European unity, NATO countries have repeatedly stated the peaceful intentions behind NATO expansion and backed this up with their behavior, avoiding buildup until recent actions by Russia, especially in Ukraine, have caused them to rethink this approach. But ultimately, these fears of Russia’s are not substantiated and not supported by NATO’s actions and approach. Rather, it is only Russian aggression against its neighbors that has the potential to make NATO and Russia threats to each other. The key for NATO’s major players is to respect Russia’s emotions while not respecting the substance of its arguments.

In some ways, Russia can be fairly accused of being a sore loser. The Soviet Union’s ideology had lost out bigtime to that of the West, and the people subjected to this losing ideology had emphatically rejected it in favor of the West’s, even in Russia. For Russia to act as if the West somehow had no right to spread and intensify political, economic, social, and military ties with so many newly oriented countries very eager to do just that amounts to the loser in a conflict trying to make conditions equal to a stalemate. Such expectations are not realistic in a conflict, whether hot or cold. It would have been like the U.S. seriously expecting North Vietnam not to spread communism to South Vietnam in the 1970s, after we withdrew. And while there are sensible reasons to argue against further NATO expansion at this time, too, I don’t believe they are as strong as the case for expansion, and will explain this later. At the very least the West can be more sensitive to Russia’s concerns about NATO expansion to its borders. It can build on and improve the existing process and institutions in which Russia has been consulted and included in all instances of NATO expansion. Perhaps, when someone like Putin is not the leader of Russia, Russia itself could be induced to join NATO and further reduce tensions, but more on that in a bit.

In the context of this NATO expansion and of Ukraine’s and Georgia’s stated desire to join NATO, Putin felt that necessary response was its military actions in Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia, and Crimea and eastern Ukraine in Ukraine, feeling the West’s interventions served as justification for his own. However, there are major problems with this comparison, as if somehow the actions are equal or the one set of actions justifies the other. Such assertions are not in line with reality. While majorities in most and possibly all these areas Russia has invaded and/or annexed want to secede and/or join Russia, all these areas were part of sovereign states, states that Russia recognized. In any democracy, there are going to be minorities that disagree. But secession as a matter of law, whether in the U.S. Civil War, Russia’s first war with Chechnya, or in Georgia or Ukraine, is generally illegal except in extreme circumstances. NATO expansion, on the other hand, was undertaken by elected democratic governments in accordance with the wishes of their people. The case with Yugoslavia is also different because so many minorities in so many parts of the country (which already had a federal constitutional structure that both implicitly and explicitly provided for legal secession) viewed the state structure as illegitimate, and in that ethnic cleansing and genocide were issues in both the earlier war and in the later situation with Kosovo, where minorities were under the threat of very real state-supported mass violence against them. Despite misleading Russian claims made both before and after Russia’s military actions, there is not currently a comparable threat to civilians in either Crimea or Eastern Ukraine, and there is no evidence of mass killing like there was in the Balkans. The Georgia case is less clear-cut, but still did not involve anything near as bad as that which was perpetrated by the Milosevic regime.

Ukraine, though, is a special case from the perspective of Russia. For Russia to see Ukraine join NATO would be a particularly strong blow to the Russian nationalist ethos, seeing that Russia has defined itself as the inheritor of the Kievan Rus’ state and the leader of the Slavs since it emerged from Mongol domination many centuries ago, and a Ukraine firmly allied and joined with the West would destroy what is left of this notion. And yet, Ukrainians have their own say in this matter. Primarily, for most Ukrainians the Maidan protests and several of Ukraine’s most recent elections are part of a war between “old guard” Ukrainians who want to continue a corrupt system of Soviet and now Russian-style patronage dominated by oligarchs on hand, and younger Ukrainians who want transparency, accountability, and a Western system on the other. Will the soul of Ukraine will orbit the older, more authoritarian, more corrupt model of Russia or the newer, more democratic, less corrupt EU model? It is clear that Ukraine’s rising generation wants to change the status quo and to orient itself with the EU, America, and the West. The West will be happy to include and welcome them in time, but it is hardly desperate to do so and does not view Ukraine as central to its interests and future.

Russia, on the other hand, does view Ukraine as central to its future and identity, as mentioned. Thus, it is willing to play at the big-money blackjack table, while the EU and the West are over at a table with chips in much smaller denominations. Russia and the West are playing much different games then, with different rules and different stakes. And this is obvious to anyone even paying slight attention to the conflict. The reality is this: whatever the wishes of the majority of Ukrainians, there is little practicable or realistic that the U.S. can do to prevent one of the world’s most powerful nations (Russia) from doing pretty much whatever it wants to a much smaller neighbor (Ukraine). The world saw this in 2008 when Russia took away two areas—Abkhazia and South Ossetia—from the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, right when the Olympic Games were occurring. Putin and Russians didn’t care then and don’t care now about world opinion on these issues. Russia knew the U.S. and Europe would not go to war against it to preserve Georgian territorial integrity, just as it knows now that the U.S. and Europe will not go to war against it today to preserve Ukrainian territorial integrity. If they wanted to, they could easily start a war with Russia and prevail with conventional arms or, should the need arise, nuclear. U.S. military spending in 2014 (after cutting down from $640 billion the previous year!) was over $580 billion, but Russia spent only $70 billion, more than eight times less. Inside NATO, the UK, France, Germany, and Italy alone spent over $180 billion together, more than two-and-a-half times what Russia spent, and this does not even include the rest of the alliance. Still, even with this imbalance, the consequences of a NATO/Russia war would be catastrophic, with anywhere from thousands to millions, or even billions, of casualties and anywhere from between large sections of Ukraine to large sections of the world in ruin, if not the whole world. No one wants this: not Americans, not Europeans, not Ukrainians, and not Russians.

In the end, Ukraine just means that much more to Russia than it does to the West. Everyone knows this. The U.S. and Europe can provide money, diplomatic support, and equipment—tons of equipment and heavy weapons, if they want—to Ukraine. But, ultimately, that will only prolong fighting and increase the destruction and bloodshed, as a far smaller Ukrainian military, no matter how well equipped, cannot win a war with Russia, especially while it is also fighting a minority of rebel Ukrainian separatists being armed and supported by Russia, too (Russia even obscenely denies that its troops are operating in Ukraine, which they clearly and provably are, though the Kremlin pressures families to keep quiet when their sons are killed in Ukraine). Ukraine will not be able to field enough trained pilots to fly advanced Western aircraft or enough soldiers to use state-of-the-art Western guns. And there is no way American or European troops will come to Ukraine’s aid with their own soldiers manning Western weapons, flying Western planes. Since that will not be done, it is nearly pointless to militarily aid Ukraine. This will simply be a matter of inflicting more pain, blood, and death on a Russia that seem quite willing to absorb pain, blood, and death to protect its interests in Ukraine. What will the U.S. or Europe gain by helping Ukraine to kill more Russian troops and Ukrainians rebels? Such action certainly won’t make Russia nicer, behave more in accordance with Western norms, or cause Russia to be kinder to Ukrainians in any kind of inevitable defeat for Ukraine. If anything, it will encourage the opposite. The only outcome, for now, is whatever outcome Russia decides it wants, which seems likely to be redrawing the map of Ukraine in favor of Russia even more than has already occurred, but will not, likely, see a full takeover of Ukraine.

The only question is, what will the final price tag be?

Let me call here for a price that is low in blood, but still high in cost.

What do I mean by this? Well, as I have stated, short of WWIII, the West cannot stop Russia from accomplishing its military aims in Ukraine. Ukraine, of course, needs to resist, if only just to show that there will be at least some price in blood for such Russian heavy-handedness, but this price does not and should not be exacted by the rest of Europe and the West. And when Ukraine’s defeat comes, terrorism and guerilla fighting against Russia is something that will only bring even greater misery to untold numbers of Ukrainians, as Chechnya (not to mention America’s experience in Iraq and both the American and Soviet occupations of Afghanistan) shows us beyond a shadow of a doubt. Chechnya also shows that, unlike Yeltsin, Putin will not cease until there is “victory” as he has defined it, even if there are thousands and thousands of casualties. Putin sent a clear message with his war in Chechnya: you can resist, you can kill us, but there is only one outcome while I am running things.

And yet, with Ukraine especially, there is much more support in the West for punishing Russia than there was in either the cases of Georgia or Chechnya. With the military option making no sense, the West has made clear their price tag to Russia: “We won’t get our soldiers’ boots dirty, but we are happy turn up the economic pressure on you and to make your regime suffer economically and your people suffer for so blindly supporting a thug like Putin who says one thing and does another, and outright lies about using force in Ukraine. This is not how the big boys choose to resolve disputes anymore and if you behave like this, that is the bill we are sending you,” the West increasingly seems to be saying.

Will this change Russian policy in Ukraine anytime in the near future? Highly unlikely, though it is possible. That does not mean that sanctions are pointless. Quite the contrary, actually. They let Russia know in a humiliating way how much more powerful the EU and America are each in comparison to Russia. They remind Russians that they are vulnerable, and that cooperation is better than conflict. They let the Russian people know that there is a lot more to the world than having a strong military and picking on smaller neighbors. They let them know of the awesome economic might that can be part of their society if they ever want to join us at the table, give them a taste of what they are missing by pursing their present general course. And, in the long-run, they will even make Putin and Russians think twice about engaging in any kind of military adventurism beyond Russia’s immediate neighborhood and beyond Russia’s major interests without international partners and backing. It invites them to think about how Russia might have accomplished the annexation of Crimea peacefully by using far more carrots than sticks, and to consider using twenty-first century approaches instead of nineteenth-century ones.

Is there a bit of hypocrisy in this? Sort of, but not really. Yes, the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003 under stupid and (unknowingly?) false-pretenses. Yes, it was reasonable to suspect Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, but yes, it was madness to invade a country based on an unproven suspicion. Also, last time I checked, America as a whole did not make any money off of this misadventure and actually lost trillions of dollars, so the idea that we did this just to make money off of oil is absurd. After 9/11, a child-like and naïve George W. Bush wanted to remake the Middle East in America’s image through military force as the solution to 9/11-like terrorism. Admirable in a sense, but mind-numbingly-stupid and hubristic. In any event, the execution of this plan was so miserable that failure was practically a foregone conclusion only a few years into the future. If Maliki had been a saint (or even an Arab Mandela) and the Middle East a place full or forgiving people and neighbors that minded their own business, even as late as 2012 Iraq could have turned out a lot better. This was not the reality, and it did not. Annexing or dismembering another country’s legally recognized territory would not fit the description of either our aims or our action in Iraq. But they do fit into a description of Russia’s recent activities in Georgia and Ukraine. Furthermore, there was a large amount of open discussion and debate in American over the last decade about Iraq throughout most of the Iraq war, but this is not the case in Russia, and Putin, as I have shown, does not allow for much debate. The U.S. also withdrew all of its troops from Iraq by the end of 2011, even though there are some advisors newly on the ground now helping to fight ISIS. In addition, Iraq has demonstrated an ability to act contrary to and independent of U.S. interests, making it clearly sovereign and not just some puppet pulled by U.S. strings. To be fair to Russia, Iraq is not on our border so disengagement from there is far easier for us than for Russia to disengage from places like Georgia or Ukraine. Thus, in many ways, even though America’s invasion of Iraq was wrong and a mistake as well, the U.S. pretty much admitted this by voting Obama into office twice and is trying (though not in stellar fashion by any means) to move past the Iraq debacle. Comparing this U.S. intervention to recent Russian military action is like comparing apples and oranges.

When it comes to any sovereign nation, it should not be for the U.S. or Russia to make decisions for it. This goes for the countries of Eastern Europe, and it goes for Ukraine. If they want to enter into an alliance with America, the EU, or Russia, that should be the choice of those countries. The truth is, NATO expansion is far from being some sort of U.S. imperialist plot; in fact, it is mainly being initiated by the countries asking to join. And, as it is, most of these countries clearly do want to stay in or join NATO, and Russia has no veto over the choices of these sovereign states, not should it. Russia should, instead, ask itself why it is not the more attractive potential partner. Why would so many the countries it used to control now so desperately want to switch allegiance to America and the West? The usual shrieking accusations of a corporate western media conspiracy and foreign NGOs turning people into fifth columnists fall far short of explaining this phenomenon. Russia will need to take a hard look at its own past and present behavior, atone, and change course if it wants other countries to voluntarily engage with it. Because the hard truth, one which Russia does not want to admit, is that it oppressed most of these people, stifled independent thought and dissent, and limited the choices and economic opportunities of millions pf people for decades. Many of these people died, were imprisoned, or were tortured, though later Soviet leaders were obviously far less brutal than Stalin. And under Putin, instead of democratizing and improving its economy in a way that broadens opportunity, Russia has become more authoritarian and now has an economy highly dependent on the natural gas and oil markets, as its recent economic woes have shown. Even as I make my final edits here, we have just learned that Boris Nemtsov, one of Russian’s main opposition leaders and one of the most prominent critics of Putin, has been found murdered near Red Square, within sight of St. Basil’s Cathedral, at the very least raising even more than usual some very uncomfortable questions about the nature of dissent, politics, and freedom in Russia and increasing a feeling of fear among Russia’s opposition activists. As for Russia’s economy, Russia’s GDP in 2013 was under $2.1 trillion, compared to almost $16.8 trillion for the U.S., while, NATO/EU members Germany ($3.7 trillion), France ($2.8 trillion), the UK, ($2.7 trillion) and Italy ($2.1 trillion) all had higher GDPs than Russia, whose GDP ranked 9th in the world by the World Bank’s estimate. There are clear reasons, then, why the U.S. and EU, with better economies and more political and social freedom, are drawing the attention and affection of Eastern Europe more than Russia is. Putin’s recent actions will only increase this trend.

But it is not just about power and money. The truth of the matter is that Russia and the Soviet Union used to stand for something. After WWII, the European colonial order oppressed millions in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, people who rose in rebellions against their colonial masters or the pro-Western, pro-capitalist regimes often installed or supported by the West. These regimes brutalized their own people and served elites and themselves and few others, leaving the masses to toil and suffer. Capitalism as practiced by these countries enriched the few and powerful at the expense of the many and poor. Some of Russia’s leaders were revolutionaries who truly believed in the socialist and communist ideals of helping the common man and empowering him for a better way of life. There was more to the USSR than Stalin oppression and tragedy and the breadlines of its last few decades. Khrushchev and his circle were inspired by Castro, seeing something of the revolutionaries they had once been in the romantic, passionate young Cuban leader, and that was a major reason why the USSR helped Cuba. Both Castro and Khrushchev believed in something greater than themselves, greater than just and a local nationalism.

In contrast, what does Russia stand for today?

That is a difficult question to answer. For the most part, it seems to stand for itself and its own power, for dominating other Slavic peoples who do not want to be dominated by Russia, and for being against America. That is hardly a love song destined to make its former subjects swoon back into its arms. Putin’s Russia “lacks both vision and appeal,” as The Economist notes. It appeals to Russians in Russia and ethnic Russians in nearby states, but any sort of mass appeal stops there. Putin’s more exclusive nationalism lacks the ring of solidarity between peoples that the USSR’s ideology espoused. To put it bluntly, Russia inspires almost no one today who is not of Russian ancestry. The reasons for this have much to with both the past and the direction in which Putin has taken Russia. All I know is, if you stand for nothing beyond yourself and your own narrow interests, if you cannot broaden your interests to encompass much of what other people dream about, your power and money are not going to inspire anyone to come to your side and believe in you when there is a better, more inspirational vision right nearby. It is human nature to often reject the more powerful for the inspirational, but Russia does not even have more power to offer. In short, there’s nothing deeper or lasting that Russia is selling that its neighbors want that the West is not selling on better, friendlier terms. The same reasons why Russia cannot win back Eastern Europe through any method other than force are the same reasons that force could not keep Eastern Europe a few decades ago and the same reasons why the Soviet Union lost the Cold War. Until Russia realizes this, it continue to be a pariah, hated and feared by its neighbors, who will generally do whatever they can to distance themselves from this hollow, unappealing Russia of Putin’s and reach out for the outstretched hands of the America, the EU, and NATO.

Some even suggest the prospect of nuclear war has significantly increased over the Ukraine crisis, that today is more dangerous that the Cold War, which is utter nonsense. Yes, the U.S./West and Russia have a clear conflict of interests in Ukraine, and yes, this conflict has gone from cold to hot.

But none of this has to keep proceeding as it is. As crazy it may seem to some, there is so much more that should unite Russia and the U.S. than should divide them. On combatting terrorism, containing the spread of nuclear weapons and other WMD, fighting poverty and disease, promoting stability around the world, bringing our economies and markets together, mutual investment, cooperation on scientific endeavors, and bringing in more countries to a global system based on the free exchange of goods, services, and ideas, both Russia and the U.S. not only have a tremendous amount in common, they have so much more to gain working together, hand in hand, rather than working against each other. And each would only be stronger from such a relationship. Yes, the prior era of friendship in the 1990s was not without major problems for Russia. But, surely, can we can try again! Imagine a world where the U.S. and Russia are allied together in NATO, working together to promote peace, freedom, health, prosperity, and stability. Imagine how badly China would want to get into the action if the U.S. and Russia had such a relationship. Imagine a UN Security Council that is not divided. Imagine the most powerful countries on earth united in a common purpose that transcends narrow self-interests and helps to peacefully empower the global south against the cancers of poverty and extremism. That is the world I want to live in. That is the world that is possible. And it is not as crazy as it sounds. There were, after all, serious considerations by Russia and NATO of bringing Russia into NATO in the 1990s. NATO expansion can only be good for current and aspiring members, then, but for Russia as well. NATO, America, and Europe, then, can all be Russia’s friends and be good for Russia, if only Russia would let them.

Russia feels the only way it can maintain its influence in Eastern Europe, though, is to oppose us and draw those countries away from us. We say, bring some vodka, come to the table, and join the party. It’s a big table, and we have a big chair for you. If Russia can change its mentality and realize this is the best way forward, and if the West can sell this vision better than it has, it will be a great party, not just for Americans, Europeans, and Russia, but the whole world, which deserves us all respecting our differences but coming together to work together in spite of them.