Putin thought he could use Ukraine’s complicated history that even divides Ukraine to his significant advantage in his massive military escalation there. He was wrong.

(Russian/Русский перевод) By Brian E. Frydenborg, May 31, 2022 (Twitter @bfry1981; LinkedIn, Facebook); this is one of a series of articles excerpted and/or adapted from Brian’s May 23 Small Wars Journal article, Bungling the Prewar and First Moves in Finland 1939 and Ukraine 2022: A Comedy of Errors for Stalin’s Soviet Union and Putin’s Russia, Respectively, his deep-dive analysis on the parallels between the 1939-1940 Soviet-Finnish Winter War that was inspired by his reading the beginning of one of the definitive English accounts of this war—William Trotter’s A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40 (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1991, 283 pages). This conflict is especially timely as Finland seeks to join NATO in light of Russia’s recent imperialist aggression.

Other articles excerpted and/or adapted from the May 23 Small Wars Journal article:

- May 23: A Terrifying Comparison Between Putin and Stalin

- May 25: A Brief History of Russian and Soviet Genocides, Mass Deportations, and Other Atrocities in Ukraine

- June 2: How Delusions of Phantom Fascists Duped Stalin in 1939 and Putin in 2022

- June 5: Moscow’s 1939 Finland Hubris Repeats Itself in Ukraine in 2022

- June 7: A Flurry of Telling Parallels Between the 1939-1940 Soviet-Finnish Winter War and Russia’s 2022 Ukraine War

SILVER SPRING—As I have noted at great length before, Putin’s brands of revanchist ethnonationalist colonialism and imperialism are utterly banal and thoroughly unoriginal, always playing on old themes from the past. On May 8, 2022, just before Russia’s grand celebration of its Victory Day commemorating the defeat of Hitler’s Nazi Germany, Putin accordingly remarked: “Today, our soldiers, as their ancestors, are fighting side by side to liberate their native land from the Nazi filth with the confidence that, as in 1945, victory will be ours,” that, “today, it is our common duty to prevent the rebirth of Nazism.” On Victory Day itself, Putin devoted much of his speech in the Kremlin’s Red Square to similar themes, calling the opposing leadership in Kyiv “neo-Nazis and Banderites.”

That latter term—Banderites—may seem puzzling to those not familiar with certain details of Ukrainian history, but it is important to understand Putin’s framing and views of this war (for much of this Banderites discussion, I have relied on this excellent Reuters Institute/University of Oxford Fellowship Paper by Christian Esch).

In the period before Hitler’s invasion of the USSR, a die-hard Ukrainian ultra-nationalist fascist named Stepan Bandera saw an opportunity and made an alliance of convenience with the Germans before the coming conflict, thinking they would be an instrument of Ukrainian independence. Bandera and some of his fighting units would roll with the Germans into Lviv in western Ukraine (recently picked off by Stalin from dismembered Poland), where he would declare an independent Ukrainian state on June 30, 1941. But this alliance lasted only very briefly as Hitler was uninterested in an independent Ukrainian state, so Bandera was arrested by the Germans and his group—the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Bandera faction (OUN-B)—became the object of a German crackdown in early July, less than a week after their proclamation of an independent Ukrainian state.

While Bandera was in captivity, his organization fought on and often engaged in atrocities against Jews, Poles, and others they wanted to cleanse from a future Ukrainian state—some had even participated in the Holocaust before becoming insurgents—as they fought against the Nazi occupation, but Bandera was in German captivity for most of this period, far away in Berlin. He was only released late in 1944—after the Germans and their allies had lost Ukraine to the advancing Red Army—to wreak havoc on the Soviets; he did not go back to Ukraine but from a distance encouraged his followers to fight.

They and other Ukrainian nationalists did, forming the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and fighting a bitter guerilla war against the Soviets that lasted until 1954 (the same year Khrushchev symbolically gifted Crimea from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, though some tiny numbers of insurgents continued resistance for years after. Not even including the fighting with the Nazis, some 150,000 Ukrainians—insurgents and civilians—were killed in combat by the Soviet counterinsurgency campaign. Bandera himself was assassinated by the Soviets in Munich, West Germany, in 1959. In Soviet memory, it was convenient to simply paint all these UPA/OUN anti-Soviet insurgents as “Banderites”—i.e., fascist allies of Hitler’s Nazis, indistinguishable from the Nazis themselves—rather than a genuine Ukrainian nationalist resistance movement, while, particularly in west Ukraine, Bandera was remembered as a nationalist hero, his extremism and the atrocities of some of his followers less remembered or excused in the context of a brutal few decades in Ukrainian history.

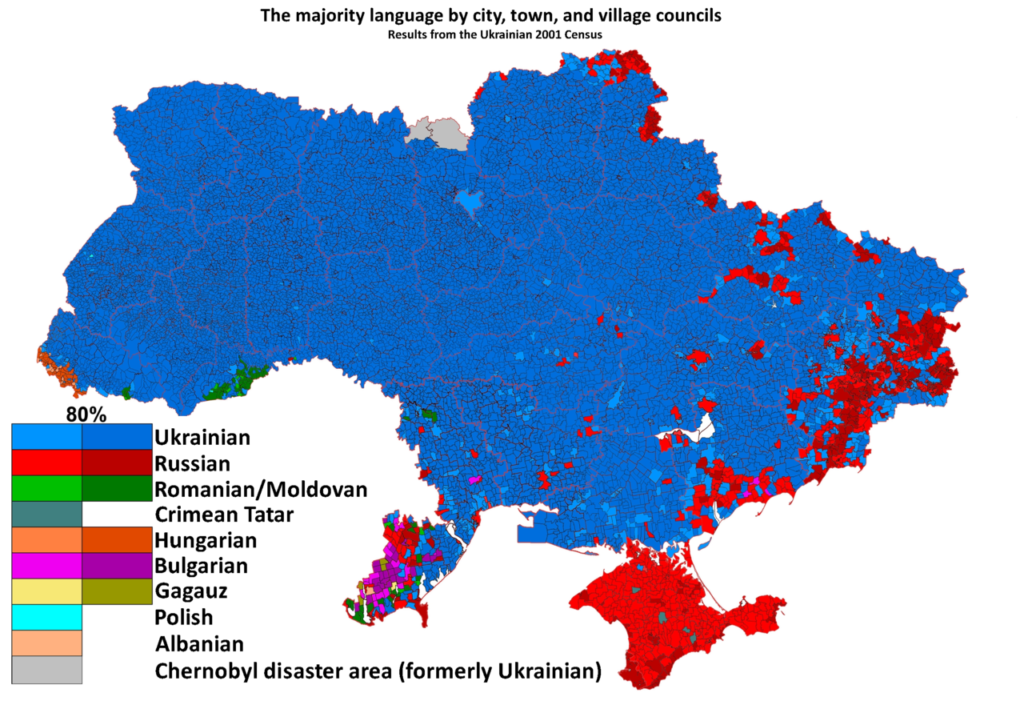

The full truth involves a combination of both narratives (not necessarily equally so), but which resonates more with a particular Ukrainian in the post-Soviet era of today has much to with geography and ethnicity in the country. While popular in Ukraine’s west and more so among ethnic Ukrainians, Bandera and his nationalists were unpopular in the east and more so with ethnic Russians.

The roots of this are deep and have tremendous bearing on the current conflict.

As I noted in a companion excerpted piece and the original deep-dive from which these pieces are excerpted, Ukraine suffered a particularly awful history of Russian discrimination against Ukrainians, up to and including genocide, mass murder, ethnic cleansing, Russian colonialism, and cultural suppression from the days of the tsars and well into the Soviet era. What resulted was a massive depopulation of Ukrainians—deported, starved to death, and/or straight-up murdered—especially in the east and the south alongside and/or followed by demographic engineering replacing many of them with Russians over a period of several centuries. It was particularly bad in the Stalin era, and some of the most intense shifts occurred in Ukraine’s east and south, regions that are currently the main targets of Putin’s iteration of his forbears’ imperialism.

Those dramatic upheavals left a lasting legacy of a significant population of non-native Russians that has played into Putin’s planning for the current fighting.

Playing into Russian paranoia of “Banderists” has been the partial rehabilitation of Bandera and his symbols in Ukraine since 1991—the year of the Soviet Union’s demise and Ukraine’s independence—first especially in the west of Ukraine but also more widely after the 2004 Orange Revolution and especially the 2013-2014 Maidan Revolution and Russia initiating war thereafter, when pro-Western, anti-Russian leaders came to power amid Russian interference, corruption campaigns, even war directed by Putin. The semi-rehabilitation of Bandera was not greeted warmly in the Russian-speaking parts of the east or in Crimea.

You can see the wheels turning in Putin’s brain, with him thinking invoking Bandera and his fighters in 2022 would galvanize many Ukrainians—especially in Ukraine’s east, and especially the Donbas’s Luhansk and Donetsk regions—to Russia’s side.

Little did Putin imagine that Russian aggression since 2014 had pushed many of them away from Russia and that his massive 2022 invasion would only dramatically intensify this process, uniting nearly the entire country behind both Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and resistance against Putin and Russia. For Ukrainians, the memories of Russian aggression against Ukraine over the past decade, it turns out, were far fresher, relevant, and resonant than those of controversies from fighting wars back in the mid-twentieth century.

See all Brian’s Ukraine coverage here

© 2022 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!