It’s possible Ukraine can push Russia out entirely (including from Crimea & the Donbas) in the coming months; here’s how that would most likely go down. If my last piece focused on the “why” Ukraine will win, this one focuses on the “how.”

(Russian/Русский перевод) By Brian E. Frydenborg (Twitter @bfry1981, LinkedIn, Facebook), August 3, 2022; greatly condensed version published by Byline Times on August 16, 2022, as How Ukraine’s Southern Offensive Could Lead to the End of the War; adapted version featured by Small Wars Journal on August 4 within Why Ukraine Will Defeat Russia and How, from Kherson to Crimea, from Zaporizhzhia to the Donbas, in turn cited by the German news site Buzzard; see the previous July 30 sister article Russia’s Defeat in Ukraine May Take Some Time, But It’s Coming and Sooner Than You Think

Morale is the greatest single factor in successful war.

Dwight E. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe

If we had only deployed our forces against the Finns in the way even a child could have figured out from looking at a map, things would have turned out differently.

Nikita Khrushchev, on relative Soviet failure in the Soviet-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940, Khrushchev Remembers

Stupid is as stupid does.

Forrest Gump

A Russian soldier enters Heaven.

St. Peter: “So you’re dead…”

Russian: “Oh no—Soviet spokesmen say I’m bravely advancing on the Finns.”

Finnish joke/@realtimewwii/Twitter

SILVER SPRING and WASHINGTON—In my last article, I already went into why the specific, major dynamics of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s absurd war will be favoring Ukraine more and more over time for the foreseeable future—why Ukraine is winning and Russia is losing—but here, I would like to get into what specifically this means for the current and foreseeable future: how Ukraine will win.

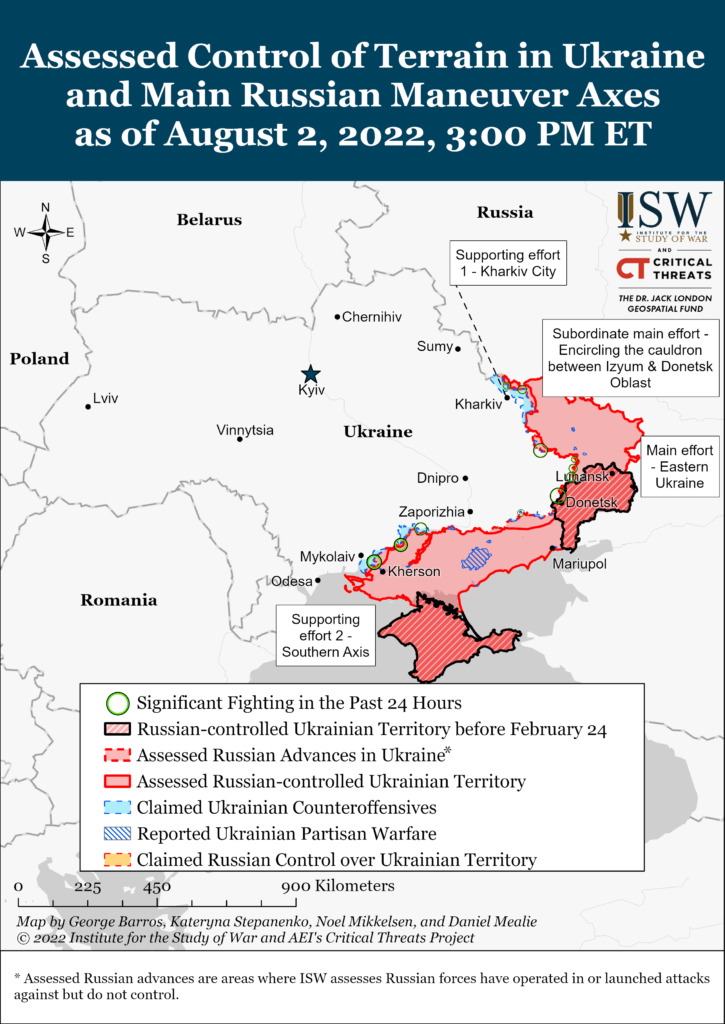

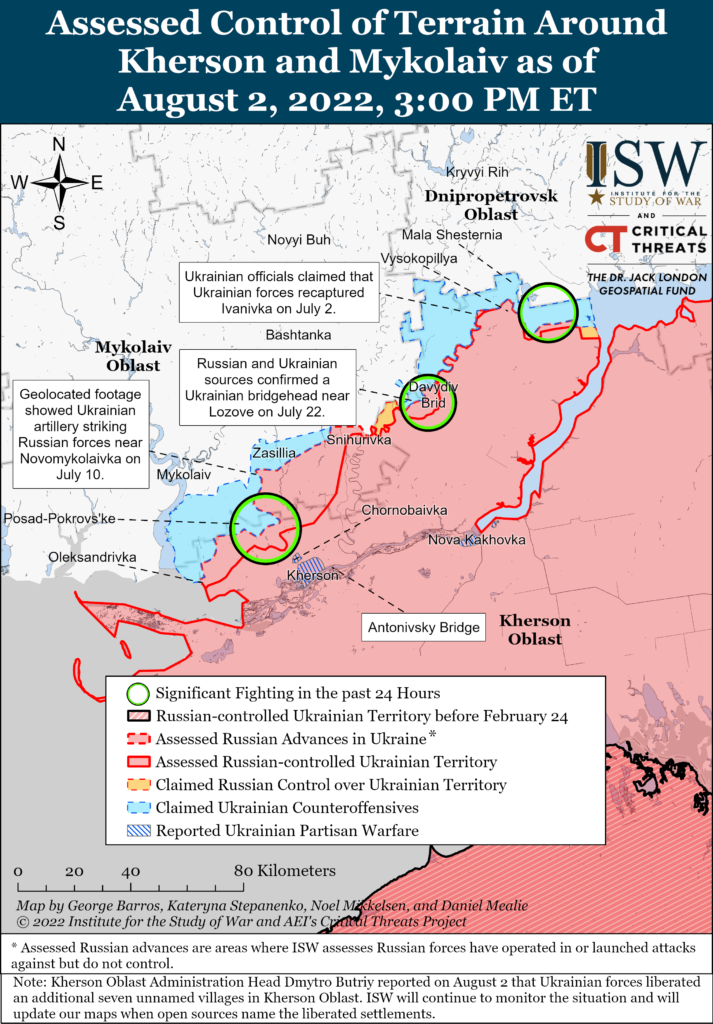

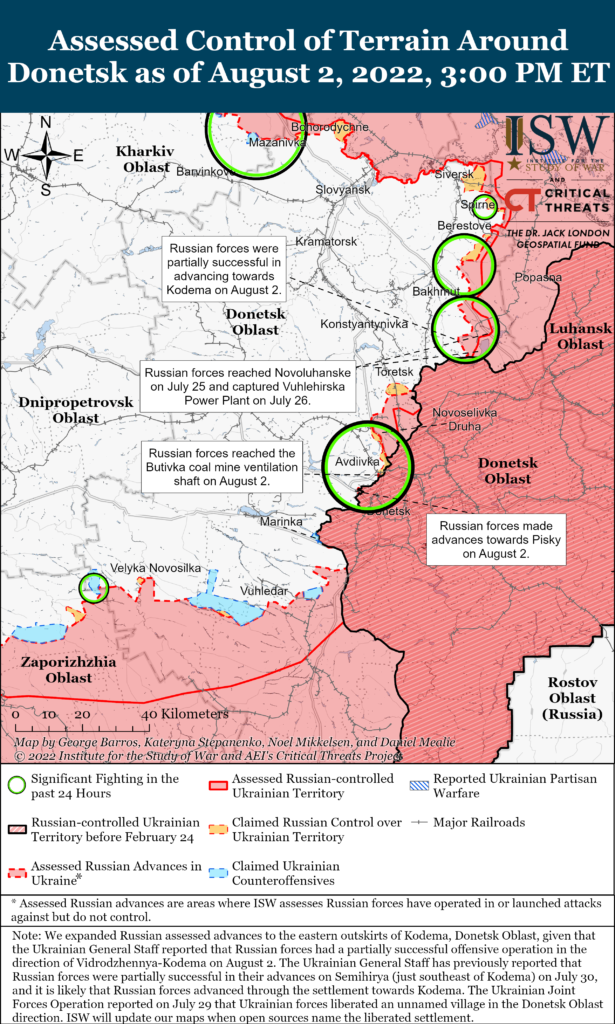

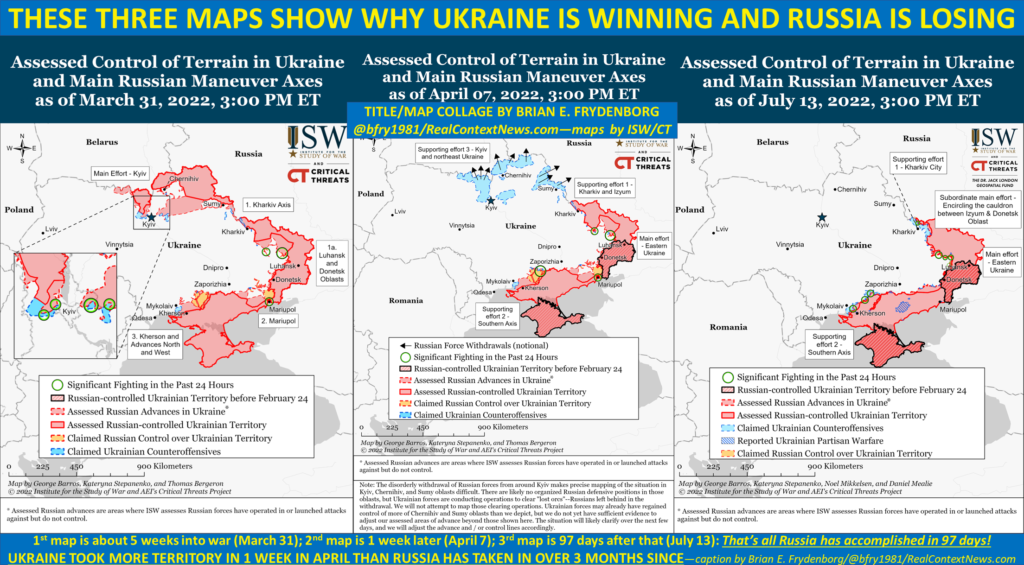

To revisit some of those dynamics I discussed earlier, Ukraine has obviously recently been making steady advances in the south towards Kherson as it advertises a massive counteroffensive there, even as it has decimated Russian ammunition depots and command centers well-behind the front line there and, especially, in the eastern Donbas. At the same time, as new Western equipment—especially HIMARS and M777s—have significantly altered the dynamics overall, including in the Donbas region with the Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts (i.e., provinces) that have been the scenes of fighting since 2014, with the Russian advance there—which had only been creeping forward unevenly and pitifully over the course of three months—having all but come to a complete halt, some minor Wagner “mercenary” success in Novoluhanske and at its nearby Vuhlehirska power plant notwithstanding, until the past few days. Yet even the most recent minor advances in the east do not portend any effort Russia can sustain, let alone that can yield major breakthroughs.

I will explain how, the more time that goes by, the more the fates of the eastern and southern fronts will be connected (indeed, even as I have been writing this over the past week, this has become only more clearly the case).

From Kherson to Crimea and Beyond

Back in April, I noted the possibilities that both Western weapons in Ukrainian hands could be a huge threat to the Russian Navy and that Kherson could fall to Ukraine, and that both would threaten Russia’s eight-year occupation of Crimea. Fast forward to now and every day (even today!) there is more and more reason to believe that Ukraine should take Kherson—city and oblast—relatively soon. Once this happens, then the rest of Russian-occupied territory in the south of Ukraine opens up to that continuing major counterattack by Ukrainian forces.

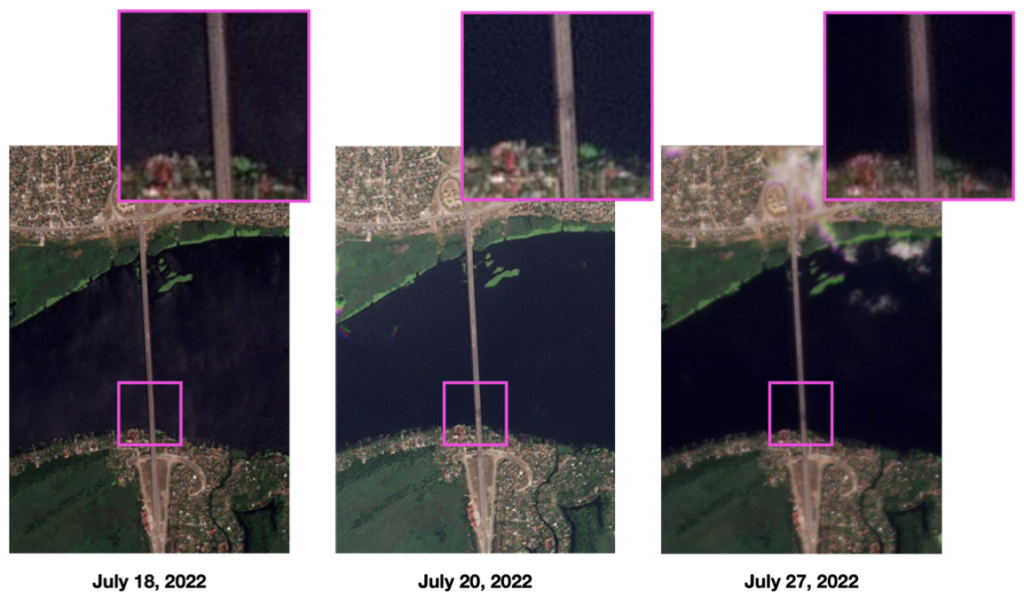

Yet, where the Russians should just play defense and conserve manpower in the south, they have been engaging in attacks that have failed and cost them lives, only weakening their defensive capabilities against Ukrainian forces. In recent days, Ukraine has even damaged the vital bridges near Kherson enough that Russia cannot use its military vehicles or equipment on them, aiming to cut off its troops on the north/west bank of the Dnipro River, on which Kherson (from now on city, unless otherwise noted) lies. After theses precise HIMARS strikes against key regional bridges, thousands of Russian troops low or soon-to-be-low on supplies are thus about to be cut off by advancing Ukrainian forces if they are not already, being set up for death or surrender unless the Russians find a creative and safe way over the river or to keep supply lines open, all under Ukraine’s watchful eyes, with pontoon bridges Russians are trying to use being vulnerable and easily-anticipated attempts at workarounds.

Kherson is only about sixty miles from Crimea’s northern border. Unlike the war-torn east with its separatist enclaves, Crimea was formally annexed (illegally) by Russia in 2014, and since then, has seen Russia only beef up its considerable presence, not just in terms of military bases and equipment and its Sevastopol Black Sea Fleet naval headquarters (which was itself hit by, apparently, a drone a few days ago), but in terms of moving many Russian security and intelligence personnel and their families even while suppressing native Crimean Tatars, altering demographics in Russia’s favor.

When Russia has been beaten back on some other fronts—Kyiv, Sumy, Chernihiv—it has been with heavy casualties on the Russian side and not some orderly retreat (Ukraine estimates over 40,000 Russian soldiers have been killed—and I argued that Ukraine’s estimate in a general sense is relatively credible—while U.S. intelligence believes there are over 75,000 killed and wounded Russians, equivalent to roughly half the original Russian force deployed, either estimate an astounding casualty rate for a large modern army over such a short period of time; open source investigations have also confirmed at least 5,000 Russian vehicles have been lost, with obviously further vehicular losses difficult or unable to confirm—or unknown in the fog of war—still having happened).

Thus, if past is at all prologue, we should not expect large formations of intact, well-supplied and well-equipped Russian troops to just be leisurely making their way back to Crimea from the Kherson front to defend it. Rather—as is already occurring—Russia is panicking as it knows it has committed most troops in Kherson Oblast and Crimea to the front and that it has very little to defend either should Ukraine break the Russian line at that front, so they are moving large numbers of troops to Kherson from the Donbas front and also from whatever was left in Crimea even as it is also moving troops to Crimea (perhaps just as a staging area or perhaps because they fear its loss too—as they should). They are also moving some of these troops into neighboring Zaporizhzhia Oblast, very recently increasingly coming under heavy Ukrainian fire, a sign of its inclusion in the general Ukrainian southern counteroffensive. (Zaporizhzhia is the last oblast between Kherson Oblast and Donetsk Oblast, the southern of the two Donbas oblasts, Luhansk being the northern one. This shifting of Russian troops from the east obviously is weakening Russia’s position in the Donbas before Russia has achieved its objectives there, a move Russia would not make if it was not nervous about losing the south.

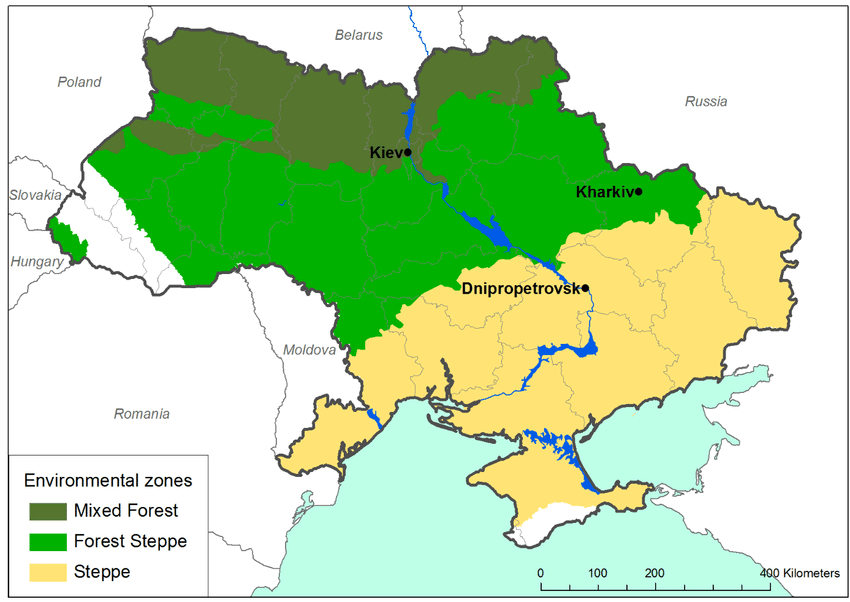

Ukraine very likely is going to able to cover the short distance from Kherson city to the Crimean border (even if perhaps slowly and carefully: Ukraine prefers to actually be careful with the lives of its troops, unlike—as I have noted before—Russia), as the terrain is not particularly defensible, just low-lying fairly flat coastal plain devoid of forests. Once this happens, that means Ukraine will have sealed off the isolated Crimean Peninsula’s few land routes north with ease, cutting it off entirely from land reinforcement routes… except for one special bridge.

A personal vanity project of Putin’s and a boast of modern Russian engineering, the (rushed and not to code, so to speak) Kerch Strait Bridge (also known as the Crimean Bridge) it not only the longest bridge ever constructed in Russian history but is the longest bridge in all of Europe, some twelve miles long. Especially using HIMARS, Ukraine could render it inoperable as it has the bridges around Kherson city and especially as Ukrainian forces move closer and closer to the Crimean border with Kherson Oblast.

When that border is sealed off by Ukrainian forces and the Kerch Strait Bridge to Russia is damaged enough to prevent resupply and reinforcement to Crimea, the Siege of Crimea could begin, with a minimal number of troops protecting the few routes north into Kherson Oblast and HIMARS, Harpoons, and other Western-supplied weapons systems keeping Russia’s Black Sea Fleet at bay or even destroying more of its vessels à la the Moskva (the sinking of which I predicted here in early April); in fact, it seems skittish Russia has already evacuated a significant portion of its fleet from Sevastopol to a port in Russia (Novorossiysk). With advanced Ukrainian weapons systems right on the northern border of Crimea after Ukrainian forces establish themselves there, any Russian naval resupply of Crimea would be risky for Russia.

Cut off by land and sea and with air supply vulnerable to Western-supplied Ukrainian air defense systems, Ukraine can dig in, boxing whatever troops remain in Crimea with that relatively small force aforementioned while the bulk of the Ukrainian forces in the south push on through Zaporizhzhia Oblast to Donetsk and the southern portion of the major front line of the war in the east. As is the case with the territory between Kherson and Crimea, there is not particularly strong defensive terrain helping any Russian defenders in Zaporizhzhia, just more relatively flat and treeless coastal steppe plains—almost entirely open fields—with a particularly low-lying corridor right on the coast and going all the way through to Donetsk oblast, including its main port city of famed Ukrainian Spartan-like resistance, Mariupol, and up to the border with Russia. Outside of cities and villages there will be nowhere for Russians to hide, nowhere they and their resupply efforts cannot be easily spotted by Ukrainian aircraft, drones, and other forces looking for targets. Ukraine’s great flat plains have long been used as invasion corridors in all directions as long as humans have lived in the region, and offer today’s occupying Russians the same disadvantages on defense as others have experienced going back to the days ancient Rome with the invasions of the Goths and Huns.

As is the case in most other places, Russia keeps attacking near Kharkiv but has little to show for it, and let there be no doubt that this front is less consequential and at best a sideshow compared to the efforts in the east and south. It would be more than acceptable for Ukraine to lose some ground there temporarily while making far greater gains in the south and weakening, maybe even counterattacking against, Russia’s Donbas eastern positions, but it does not seem like Russia is poised to make any major gains on this front, either.

For the reasons outlined in my last piece, the dynamics of this phase of the conflict are pretty set and they overwhelmingly favor Ukraine, with Russia not having the ability to alter them significantly. This means we can expect steady gains in the south for Ukraine and a generally weakened position for Russia in the east. Even if it is able to soon deploy replacement troops, they will be mostly green and not particularly well-equipped.

Considering Russia’s Redeployment

July has seen the end of one phase of the war and the beginning of another, with Russia now trying to stave off disaster in the south by taking troops from the east that are still much-needed in the east, and yet, Russia has little choice: if it does not reinforce the south, it risks having almost all of its position there being steamrolled rapidly by the coming Ukrainian onslaught.

I wrote most of this before Russia moved troops from the east to the south, but while I was busy finding specific sources I had come across over the past month to cite throughout, it happened. But before it was clear Russia was pulling troops from the east, I was writing that the best Russia can probably do is weaken its eastern front to slow down the Ukrainian advance in the south, but not enough to really stop it, because that could precipitate a collapse on the eastern front. So far, that seems to be the path the Russians have chosen: weakening one front even after they had pretty much already stalled there to reinforce another front where they would have been crushed relatively quickly if they did not reinforce from that first front, with the most likely result that they will lose on both fronts, just less quickly in the south and now more quickly in the east (as opposed to really quickly in the south and less quickly in east).

Such is the dilemma—the trap—in which Russia has found itself: choosing how quickly or slowly to lose on one front or another, any serious victory out of reach regardless of any decisions about conventional forces (unless Ukraine starts suddenly making disastrous choices on the battlefield) and I seriously doubt Putin will use nuclear weapons, which could hurt Russia in the long-run more than any imagined gains Putin thinks their use would get him.

As much as anything else, Russia needing to move forces from one front where things are already going badly to another where things are going even worse is as much a sign as anything else of Russia’s generally weakening, losing position in the overall war, which the Kherson counteroffensive is about to expose for all to see beyond doubt.

When it comes to this reinforcement effort in the south, consider that most of those troops are in units that have been fighting in the east for a long time, taken many casualties, are exhausted, and will have to travel in a long radius around the front line to get to the south and may come under fire in transit, that will be fighting in more exposed, less defensible terrain with fewer fortified positions than in the Donbas and with longer supply lines to maintain than that front. So the idea that they are going to fare well against the extremely well-executing, highly motivated, and well-equipped Ukrainian troops that are currently having success after success near Kherson is quite a hard sell.

Additionally, if Putin and his commanders are dumb enough to focus on attack and, as a result, Russia likely suffers heavy casualties, they will be wasting an opportunity to buy time by having those troops play it much safer and dig in where they can to defend southern Kherson Oblast and Zaporizhzhia; after such failed attacks, reduced Russian forces will be even less able to defend than if they had not attacked, but, again, with the dynamics as they are, it is mostly a question of how much Russia can slow Ukraine down and exact a higher cost on Ukrainian forces in the south than actually stopping Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

While all this is going on, if Russia is not careful (and let’s be honest: when has it been?) it could even leave itself vulnerable to counterattacks in the east (if it hadn’t already even before this redeployment) while the Ukrainian counteroffensive in the south progresses.

The Key Battle to Come After Kherson: The Southern Donetsk Flank

The moment of truth will come when Ukrainian forces attacking in the south push their way to the point of being able to join forces with their fellow soldiers who have been manning the line in Donetsk Oblast at the southernmost area along the north-south Donbas axis. This could very well be some of the fiercest fighting of the war, for, if Ukraine can push back the Russians there, they will be able to flank the entire Russian line and roll up most or all of the Donbas front, especially if they are able to mount simultaneous attacks from their older 300-mile-line line on that front, where the Russians have already stalled, taken heavy losses, and are at their logistical wit’s end.

Russia has been stalled and exhausted in the east now for weeks until very recently, and it is already having to cannibalize the Donbas-front forces to attempt to prevent disaster in the south. As stated, it is doubtful those exhausted or any new, inexperienced troops will be able to stop the highly-motivated, larger, and better equipped forces Ukraine is going to throw at them (and the careful Ukrainians will probably advance slowly to bait Russia into attacks that will lead to higher Russian casualties and fewer Russian troops defending when Ukraine does attack). So, again, it is unlikely those redeployments will be able to prevent this battle from happening. On either front, the also Russians have no effective counter for Ukraine’s most advanced systems recently supplied by the West. On top of all this, Ukraine has far more reserves available. In other words, it doesn’t look good for Russia.

Taking all this into account, when this Ukrainian force finally makes it to the east and threatens to flank the whole Russian line there, this will be after Russian forces overall have taken heavy losses and the Russian soldiers on the Donbas line will still face many of the same imbalances they have already been facing lately but with far more Ukrainian troops engaging them than before. Simple math suggests it is more than likely that the combined Ukrainian forces, turning the southern front into an extension of the eastern Donbas front, will be able to push back a Russian force currently stalled or making only minimal gains with far fewer Ukrainian troops there now than will be the case when the Ukrainians now outside Kherson finally make their way there and link up with the bulk if their fellow Ukrainian forces in the east. And in some areas the Russians will be facing attacks from Ukrainians from new lines instead of the ones they have been fighting on, making their defensive positions weaker. And any new Russian troops arriving there around this time, as is the case in general, will not be elite forces (even if some veterans are among the ranks) but rushed-into service, ill-equipped, barely-trained new recruits. And while the terrain in the east is somewhat better defensively, consider this: where the Russians have advanced their positions, they will not be as fortified as they would be in their positions long-held before Putin’s February 24 blunder of an escalation.

I would say a best-case scenario for the Russians are that they are pushed back to their old, highly fortified positions from before February 24, but even this seems wishful thinking if you are the Russians: if the Russians are pushed back that much the state of the surviving troops will not be good, and they will likely be facing Ukrainian forces that are able to outflank them coming from the south (and who knows what would happen north in the Kharkiv area, though a static situation is probably the most likely one). Even if Russia avoids being outflanked in the south, it will almost certainly have to extend its current line in the Donbas to stop this, spreading its forces much more thinly and weakening the entire line in a way in which it might be mostly pushed back all at once, if the Russians have the sense to fall back as line. If not, one or more Ukrainian breakthroughs would likely result in a general rout—as happened most notably outside Kyiv in early April—or several battles where the Russians are outflanked, thus at a severe disadvantage, and suffer grievous casualties.

The most likely optimistic version for the Russians of this last phase of this campaign would be that Ukraine breaks the main Donbas line but that Russia is able to maintain, for at least a while, some territory in Ukraine near the Russian border, as Ukraine has pledged to the Biden Administration not to use HIMARS to strike targets inside Russia, a move that Biden and his team feel could possibly cause Russia to escalate much more dangerously; and yet, if Ukraine will end up being able to fully push Russia out if it is able to use HIMARS on Russian military targets inside Russia near the Ukrainian border—targets that would be the only thing enabling Russia to hold onto Ukrainian territory near that border—I would think the U.S. might be flexible on that restriction.

And while all this is going on in the east, whatever troops have been holed up in Crimea will either be forces into stupid counterattacks to break out into Kherson Oblast that will very likely fail or those forces will be whittled down to a deeply weakened state that will make any Ukrainian attack that much easier (Ukraine may or may not feel content to keep up the siege, as opposed to carrying out an invasion, depending on a how things are going there and elsewhere). And, while the locals are mostly pro-Russian, that sentiment will likely have declined and, for reasons I have outlined back in April, I don’t expect those locals to engage in any kind of mass insurgency.

Bet on Ukraine (Don’t Bet on Russia)

That’s it folks: much better, numerically superior Ukrainian forces under much better leadership with much better weapons and equipment, much better morale, and a much better supply situation are going to clash with Russian forces inferior in all of those aspects. It is hard to not see these Ukrainians eventually make their way to the Donbas and roll up or push back the main Russian line there at terrible, irreplaceable-anytime-soon-for-Russia cost. It may take a while, and Ukraine will certainly suffer casualties of its own, perhaps also high, but Ukrainians have the will, resources, and leadership to do this and the Russians have none of those to stop them.

If you still doubt that Russia could really lose this badly, ask yourself this: where will Russia get high-quality troops and top-of-the-line equipment, let alone troops with anything approaching high morale, to be able to deploy in the south or the east to stop the coming Ukrainian onslaught? They can now barely supply their own artillery in the east, their best advantage in this war, and I would challenge anyone to explain how this current situation—already bad for Russia—improves overall and consistently over the coming days, weeks, and months. Russia has no answer to this question, and thus little hope against their determined and far more confident, qualitatively-better Ukrainian foe that is redefining the playbook on modern warfare.

The battles for Kherson, and the moment when the Ukrainian southern forces can join their brothers in the east and position themselves to flank the entire Russian line or force it to fall back, will very likely be the key remaining fights of this war. Russia might manage to hold onto some pockets of territory for a while—including a Crimea isolated and under siege—but there is real reason to think the defenders in these places will eventually cave after the rest of the Russian forces are killed or routed, hampered by their consistently awful supply situation and laughable Russian leadership. And morale matters: when it breaks, many soldiers can be rendered combat ineffective even without being killed, wounded, or captured.

Any subsequent competent, well-provisioned new attacks from Russia will be coming beyond the foreseeable future (unless Russia is dumb enough to keep wasting raw recruits, and hey, it may very well be) and after Ukraine is able to strongly reinforce and fortify its positions, which will likely be their legitimate, internationally recognized borders with Russia or a small buffer-zone, a situation that would likely be a stalemate over time and once that would cause Putin’s support at home to crater over time, having nothing but defeat to show his people after so much blood and treasure and reputation has been expended, something I argued would be the end result at the beginning of this conflict, back in in early March for Small Wars Journal.

We can sure hope, and while so often hope is placed on flimsy shoulders, I really, really like Ukraine’s odds for all the reasons outlined above.

This article mainly constitutes the “how” Russia will lose; the previous sister article: the “why!”

See all Brian’s Ukraine coverage here and his July 14 precursor article, THE THREE MAPS SHOWING WHY UKRAINE IS WINNING AND RUSSIA IS LOSING (and why is isn’t even close)

© 2022 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see Brian’s eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed half-a-million content views on 8/27/22!!

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!