North Korea’s brutal, tragic history is the key to understanding why options for dealing with Kim Jong-un and his troublesome nuclear ambitions are so bad and limited, and why we are at such a dangerous moment in history as this crisis continues to unfold.

Originally published on LinkedIn Pulse October 18, 2017

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter@bfry1981) October 18th, 2017

AP Photo/Hank Walker

AMMAN — I’m 35 years old and I can’t remember ever seeing anything so alarming in relation to the Korean Peninsula as what has been happening in the toddler-months of the painfully birthed Trump Administration. Obviously, there has always been a tremendous amount of tension there since the Korean War ceasefire was reached in 1953 (that’s right, just a ceasefire: the war never formally ended and is still technically ongoing even in 2017). But things are happening so fast since Trump took office, and the main actors so comfortable with hyperbole and brinksmanship, that we can safely say that we are now in more danger of having war erupt on the Korean Peninsula than at any time in decades.

But to understand where we are today, and where we may be going, it’s imperative to understand some history, and far more and far earlier than the start of the Korean War in 1950.

Imperial Entanglements

Koreans as something of a distinct people go back thousands of years, and from quite early in their history, being on an isolated peninsula and in relatively inhospitable parts of Manchuria and Siberia, they tended to absorb and reinvent culture (an ability/trait that would become very Korean) from the neighboring Chinese. In the first century B.C.E., three major kingdoms emerged, and by the mid-seventh century C.E., one of the kingdoms emerged to defeat the others with the help of China, then turned on China to drive its forces out of Korea.

The following centuries were generally filled with disorder and rebellion until a new kingdom reunified Korea in the tenth century, but it would eventually come into brutal and devastating conflict with the Mongol Empire in the thirteenth century C.E. Koreans put up quite a fight but eventually came to vassal terms with the Mongols, retaining formal independence for their efforts, unlike many others.

A new dynasty took over in just before the fifteenth century, but would suffer a depopulating cataclysmic invasion at the hands of the Japanese and the end of the sixteenth century, one they were able to pyrrhically beat back, but only several decades later they were defeated by the Chinese Qing dynasty, and though they retained independence, the Koreans were forced to become part of China’s international tributary state system and give China control over its foreign policy; a resentful peace ensued in which Korea seldom had contact with the outside world and because of this isolation, Korea became known as the “Hermit Kingdom” from this period onward.

By the late nineteenth century, with Qing China in decline and coming under Western pressure, and with ambitious Russia and Japan eyeing Korea, the days of conflict were about to return to Korea.

Like Korea, Japan was forced to pay tribute to China for centuries, but did so less consistently and did not suffer the full vassal status that surrendered foreign policy control to China that Korea did. Like all Asian nations at the time, Japan was forced in the mid-1850s to contend with encroaching, predatory Western powers and was forced to “open” itself to Western trade and influence; this caused a great deal of unrest that culminated in the Meiji Restoration/Revolution of 1868, from which point Japan would start its rapid rise in power and modernization that would culminate in ill-fated war with Western powers in WWII.

Especially after 1868, Japan’s leaders, scornfully observing its nominal overlord China suffer humiliation at the hands of Western powers, sought to emphatically alter the balance of power that had been the political reality in Asia for centuries, with China as the unquestioned center of power. Caught in the middle would be Korea, over which Japan sought to extend its power and influence (especially as Russia was encroaching on Korea’s northern border), even though technically both Japan and Korea were part of the subservient China tribute system. Among other reasons for targeting Korea, Japan felt Korea’s geographic proximity was a major security risk to its homeland, while the traditionalist Koreans looked with disgust on Japan’s Westernizing ways and as to ancient regional values and identity.

Japan would take aggressive actions to alter the status quo and to open Korea to its trade, just as the U.S. and other Western powers did with Japan years earlier, but Japan’s diplomatic efforts could not sway the stubborn Koreans. By 1871, though, Japan had begun a formal diplomatic process of redefining its relationship with China, itself facing the brunt of Western pressure in East Asia. Korea’s stubbornness made many Japanese leaders feel it deserved to be punished with an invasion, and this idea was even encouraged by America’s representative to Japan. Though divided, Japan’s leadership decided to bide its time rather than invade Korea, instead opting for a strike against the weaker and more isolated island of Taiwan, nominally under Chinese control, in 1874, a step that further highlighted the rise of Japan at the expense of China. After a series of confrontational incidents, in 1876, Japan was able to extract from Korea an “unequal treaty” of the kind imposed by Western nations on Japan and China, in which Japan was clearly given better terms and the prying away of Korea from China’s traditional sphere of control and influence was firmly begun.

Finally realizing that their traditional vassal-state empire was disintegrating before their very eyes, China’s leaders belatedly decided to reassert China’s influence on the Korean Peninsula. Over the next two decades, China and Japan would seek ways to outdo each other’s trade advantages, power, and influence when it came to Korea, which, in turn, seemed to accept the necessity of modernization, though Koreans were deeply divided as to how to go about it; infighting only made the Koreans weaker, even as China now found itself competing in a Korea where it had just recently enjoyed centuries of unquestioned dominance; the more traditional Korean royal court favored China but younger reformers favored Japan. As tensions mounted, both China and Japan moved troops into Korea, with war nearly breaking out over a coup attempt in 1884, but in 1894, mounting tensions and a peasant rebellion would finally spark war between China and Korea; Japan’s more modern military easily defeated the larger Chinese forces and by 1895, a humiliated China was asking for peace from a Japan that had invaded mainland China and had secured sea lanes to Beijing and islands near Taiwan; in the peace treaty that followed, China ceded Taiwan to Japan and rescinded any claim of formal authority over Korea, allowing the Japanese to conquer the former and to dominate the latter.

Japan would trounce Russia in 1904-1905’s Russo-Japanese War, keeping another major power out of East Asia and making clear to all that Japan would now be the dominant power in East Asia, one that, significantly, could also take on Western powers. American President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt even mediated an end to the war, and though he publicly maintained neutrality, unbeknownst to the world at the time, he undertook this mediation at the secret request of the Japanese. In fact, Roosevelt privately very much favored the Japanese, wrote “I should like to see Japan have Korea,” and even desired that Japan would become a hemispheric hegemon just as the U.S. had become in its hemisphere. Still, he publicly kept up a neutral stance to the degree that the Japanese were frustrated by the U.S. negotiated-treaty, which denied Japan an indemnity from Russia and left the Japanese wanting more.

Korea had been sold out by the U.S. and was formally annexed by Japan in 1910, which began a period of brutal colonial Imperial Japanese rule that would not end until Japan’s defeat in WWII in 1945; the Japanese were hated when they left and still are very much hated in Korea today.

The Long Shadow of WWII Over Korea

Starting in 1931, Japan would use its base in Korea to begin expanding into Chinese territory in a conflict that would merge into WWII. Strangely enough, Japan’s puppet state in Chinese Manchuria would become a well-planted garden of future East Asian politics. During that war, a Korean named Kim Il-sung fought under Chinese Communist and Soviet leadership as the Japanese in Japanese-occupied Chinese Manchuria and distinguished himself greatly. Koreans actually formed the bulk of the anti-Japanese in Manchuria, and one of the main Japanese figures in Manchuria, against whom Kim fought, was Kishi Nobosuke, who served as Japan’s prime minister from 1957-1960; his grandson is Abe Shinzo, Japan’s current Prime Minister, so, yes, that means Kim Jong-Un’s grandfather fought against Abe’s grandfather. Additionally, the Korean Park Chung-hee fought for the Japanese occupiers in Manchuria and specifically against guerillas like Kim while wearing a Japanese uniform; he would overthrow South Korea’s democracy in 1961 and install a military dictatorship (one that relied heavily on other Korean collaborators with Japan from WWII) that would last until his assassination in 1979, only to be replaced by a new dictatorship that would last until 1987; his daughter, Park Geun was president of South Korea from 2013 until her impeachment and imprisonment earlier this year.

As for Kim, while Chinese communists returned to prioritizing fighting the Chinese Nationalist government after WWII, Kim and a cadre of other Koreans who had fought as guerillas came back to Korea under the patronage of the Soviet Union. There was no clear specific Allied plan for Korea after Japan surrendered, but the Americans proposed to the Soviets dividing Korea into occupation zones at the 38th parallel and the Soviets agreed. Soviet forces had already made their way into a sliver of northeastern Korea, and the Americans would belatedly make their way into the south. With all the division and confusion, neither appeared eager to have full responsibility, but once assigned a formal zone, the Soviets quickly established control and order, while the Americans did anything but, engaging in what was perhaps the most poorly planned and executed occupation until the launch of George W. Bush’s Iraq misadventure in 2003. The Americans did not even feel that Koreans were ready for self-rule, soon came to view them as enemies that needed to treated as a surrendered (rather than “liberated”) people, and avoided using the divided, preexisting political groups (ones that that had already started on the path to self-rule) to form any kind of Korean government, though the Americans did favor conservatives since they were anti-communist even though the environment was one in which the long-oppressed (by both Japanese and Korean overlords) Korean masses favored leftist candidates; since America’s main reason for being in Korea was to contain Soviet expansion, it was hardly eager to set up a democracy that would be ideologically disposed towards the Soviet Union; in fact, they even kept many of the hated Japanese in low-level bureaucratic and security positions, while the Soviets were quick to sweep away Japan’s colonial structures in the north. Though Americans and Soviets were publicly committed to trying to forge a single national Korean government, the American zone only became more fractious internally and the Americans increasingly favored un-representative rightists and those who had collaborated with the Japanese, while by February 1946—after some initial atrocious behavior by Soviet troops who were then replaced by more disciplined, restrained troops—the Soviet had stifled dissent and seen to it that Kim and the Communist Party were leading a proto-government; clearly, prospects for a unified government were dim. Also at this time, Western-Soviet relations were rapidly deteriorating; by the fall of 1947, it was clear the U.S. and Soviets would not come together on Korea and that Korea would be divided. Later in 1948, a new U.S.-backed Republic of Korea (ROK, a.k.a. South Korea) emerged south of the 38th parallel and a Soviet-backed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, a.k.a. North Korea) emerged north of the 38th parallel, each with clearly stated designs on ruling the entirety of the Korean Peninsula.

The Soviets were confident enough in what they had built that they fully withdrew their occupation forces from DPRK in 1948, well before the U.S. had fully withdrawn their occupation forces from ROK in mid-1949; both sides, though, left military advisors.

Kim would be in firm control of DPRK while his counterpart could hardly claim the same for the south after several years of inept U.S. policy, and while each side sought to unify the Peninsula under its own control, only Kim and his DPRK were in a position to do so as ROK was destabilized and fractured within its own borders, but that didn’t stop Syngman Rhee, ROK’s leader, from devising his own plans to take over the whole of Korea just as Kim was doing the same. Their American and Soviet patrons were not as eager for war and sought to restrain their clients’ offensive ambitions. In particular, Kim almost nagged Stalin for permission to invade the south, but Stalin repeatedly declined to give his assent. By the end of 1949, the Soviet Union had conducted its first nuclear test and mainland China was then firmly under the control of Mao’s Chinese Communists, who trounced the American-supported Nationalists and drove them to Taiwan, meaning the U.S. would be nervous about further communist gains in Korea during 1950. Likewise, Stalin and Kim were nervous that, with U.S. aid, ROK (and perhaps the strongly anti-communist Japan and Nationalist Taiwan) would eventually be much more powerful and seek to unify Korea under ROK control, just as Rhee was threatening, and South Korean forces actually crossed the 38th parallel repeatedly to conduct operations in North Korean territory not long before the Korean War erupted in 1950.

In January 1950, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson gave a speech that would later become infamous, with many later blaming it for the start of the war. In that speech, South Korea was conspicuously not included in what was defined as U.S. vital national interests, meaning there was no U.S. guarantee of military protection and defense in the event it was attacked by communists. It was thought that this essentially gave a green light to Stalin and Mao to do as they please in Korea and that this was why Stalin gave his blessing to Kim in April for an invasion. Such was the conventional wisdom, anyway, until Soviet archives later painted a much more complicated picture…

North and South Korea, Seeking War

Both before and after Acheson’s speech, Stalin was concerned that the U.S. would intervene directly into the conflict if North Korea attacked South Korea, even right up until the outbreak of the war, and wanted above all to not risk a major confrontation that could erupt in war between his Soviet Union and the United States. In other words, Stalin feared U.S. intervention on the Korean Peninsula regardless of Acheson’s 1950 and even rejected a formal defensive alliance with DRPK in 1949.

Acheson himself didn’t see the speech as a “green light” to communist attacks on ROK, but regardless of his intent, rhetorically his speech did anything but convey a clear American commitment to ROK’s security or that the U.S. was prepared to counter DPRK, Soviet, or Chinese actions towards ROK. The incompetence here mirrored the same incompetence of the U.S. occupation of southern Korea, and the communists wouldn’t have been irrational to interpret the speech as conceding Korea if it came to a war. Despite a general picture from the West of Stalin being hell-bent on world domination, then, it was a cautious Stalin who refrained from taking that speech as a “green light.” Quite strangely, an incorrect report in The New York Times actually convinced DPRK that South Korea was within the U.S. military protection guarantee.

By the middle of 1949, both the Soviets and the DPRK were apprehensive of the military buildup in the south and an American-supported invasion of the north from there, but Stalin was firmly against Kim’s plan to invade the south. Mao and the Chinese were more generally supportive but repeatedly stressed that the timing was too early, especially as they were still fighting their civil war, though they did pledge to come to Kim’s aid if he needed help; in other words, the Chinese wouldn’t be there from the beginning, but if things went badly enough, they would intervene on Kim’s behalf. Kim’s overtures to Mao made Stalin more nervous about the outbreak of war, and just before the Americans withdrew from the south, he resolved on a policy of supporting Kim enough to discourage an attack from the south but not enough to encourage Kim to attack from the north. So it was that over and over and over again, Stalin told Kim an emphatic “no” when it came to invading the south. And when DPRK forces initiated clashes with ROK forces along the border late in the year, Stalin was furious. At the same time, Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic of China as he was routing Nationalist Chinese forces from most of China and taking over the country. This made Stalin even more cautious, as he wanted to assess the situation with a newer, additional center of communist gravity in Mao’s China. Thus, as 1950 dawned with Mao’s Chinese Communists firmly in control of mainland China, Stalin took a more passive approach to Korea. Hardly a fool, Stalin would have realized how China had long regarded Korea as under its influence, and either may not have wanted to alienate the only other major Communist power in the area by asserting too much of a role in Korea or may have hoped, nervous of an eventual conflict anyway, that the Chinese would intervene to the degree that they would prevent the need for a massive Soviet intervention to support DPRK. Whatever Stalin’s calculation in this regard, Kim engaged in a policy that still defines North Korean policy today: playing Soviets/Russians against the Chinese to try and get more out of each.

Of course, the Nationalists being driven from mainland China raised alarm bells in the minds of American planners. And they had reason to be alarmed: where the Soviets quickly installed Kim Il-sung as a leader in the local, dominant communist party, the Americans dithered, stumbled, and nurtured instability and division in the South. There was so much unrest and brutal fighting among factions in the south even before 1950 that research indicates between 100,000 200,000 people were killed in political violence by either ROK forces or U.S. occupation forces in the years before the war, and once war broke out, a further 300,000 were killed or “disappeared” at the hands of the ROK government in just the first few months of the conflict. Much as was the case with South Vietnam years later, in South Korea the U.S. was supporting a government that was highly oppressive to its own people and hardly worth fighting for, a tragic situation that was far less forgiving in the Vietnamese case.

In the months after Acheson’s speech, Stalin would make preparations for war alongside DPRK, in particular sending specialists, advisors, and technical assistance without actually endorsing war or invasion as a course of action, further reflecting his caution. He would also continue to demonstrate concerns about possible American intervention in the following months. And yet, he also became more comfortable with the idea of a northern invasion of the south after the victory of Mao in mainland China and his agreeing to a new treaty with the Soviets. Stalin also felt more secure as the Soviet Union had only just recently conducted its first successful nuclear weapons test, ending the American monopoly on that technology and creating a nuclear club of two. Stalin’s fear that American and even Japanese troops would invade the Soviet Union, after all these considerations, must have seemed much less of a possibility, yet even when Stalin finally approved in April Kim’s request to be able to invade the south that summer, he did so only on the condition that Mao also approved the plan, which Mao later did, though reluctantly. Furthermore, Stalin had only approved a limited offensive, only reluctantly assenting to a full-scale invasion mere days before the planned invasion and the start of the war amid reports of a buildup of South Korean forces on the border, in part because the thinking was that if the North won a quick war, it would keep the U.S. out, but that a long war would draw the U.S. into the conflict and a stronger offensive was more likely to achieve a quicker victory.

In the end, it was Stalin’s fear that the U.S. would support a South Korean struggle against North Korea that held back his approval of Kim’s desired invasion for so long, and his fear that the U.S. would eventually support a South Korean takeover of North Korea that led to his to the same invasion and its expansion.

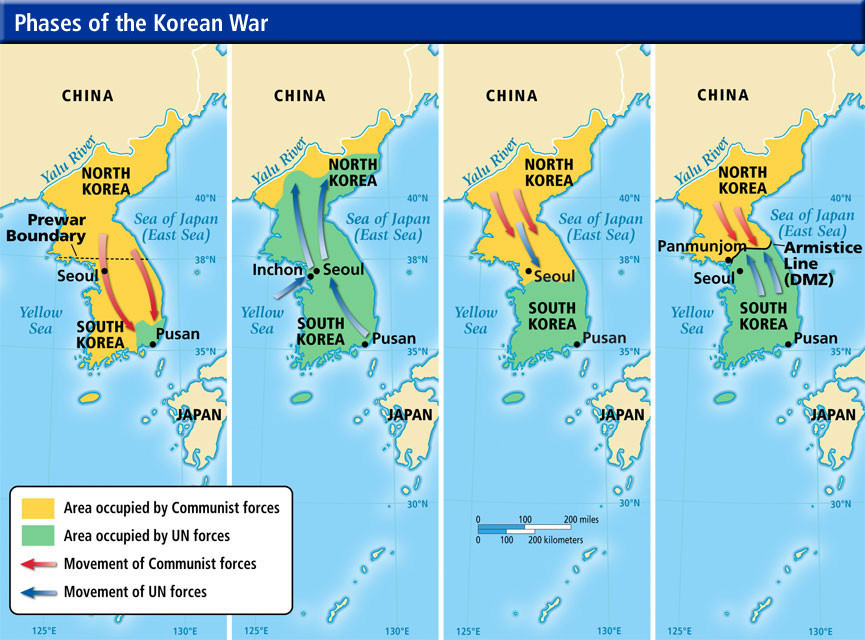

The Terrible Cost of War

It turns out Stalin’s concerns about U.S. interference had been correct: when DPRK forces overran Seoul, ROK’s capital, just days after the invasion and continued pushing South Korean forces south, the U.S., mustering the support of United Nations (the USSR was boycotting it at the time because the UN would not seat Mao’s representative in China’s seat), deployed to fight alongside ROK against the DPRK invasion, but even so, they kept losing ground and were in danger of being annihilated at the bottom edge of the Korean Peninsula; the U.S. then launched a counterattack that involved an amphibious landing behind North Korean lines, and in the ensuing counterattack, the mainly-U.S.-and-South Korean- forces pushed North Korean forces all the way to the Chinese border in October, which only invited a massive Chinese counterattack that, by the middle of 1951, had resulted in a stalemate back along the 38th parallel.

TES.com

It is important to note that both the U.S. and China only directly intervened when the situation was dire for each of their clients.

Gamma-Keystone via Getty

The war was terrible for Koreans. Atrocities were common on both sides, American forces included. About three million Koreans died, one in ten people on the Korean Peninsula, but far more died in the north, where 12-15 percent of the whole population died. The U.S. ran a brutal air war against North Korea, one which resulted in probably the most utter and complete destruction of any single nation’s infrastructure, cities, towns, and villages since the times of the great Mongol massacres and perhaps, arguably, of any period in history. In the early months of the war, the North Koreans were essentially defenseless against U.S. air attacks (as were many of the South Korean civilians unlucky enough to be mixed in with occupying North Korean forces). And yet, there was a degree of American restraint in the bombings as U.S President Harry Truman did not want to provoke a wider ground war with Soviet or Chinese forces, which had not entered the conflict; this relative restraint vanished after Chinese ground forces entered the war. In fact, more bombs were dropped by the United States during the Korean War than Americans dropped in the entire Pacific War during WWII, including nearly twice as many tons of napalm, which only during the Korean War had reached a level of high appreciation on the part of senior U.S. military planners, setting the stage for its far greater future use in Vietnam.

Targets even included livestock and farming essentials, and the population that survived was driven down to underground facilities. By the fall of 1952, bombing had been so successful that virtually no targets remained. Eventually, targeting expanded to include major dams, with catastrophic results for the population. By the end of the war, nearly every man-made structure in North Korea had been destroyed by U.S. bombing raids, and, apparently, “only two modern buildings remained standing in Pyongyang” when the fighting stopped; this level of destruction was well understood by those involved at the time.

The war dragged on until July, 1953 (and, had it not been for Stalin’s death in March 1953, it might have dragged on longer, but the Soviets who took over after Stalin died had no desire to continue supporting the war effort in Korea), resulting in a cease-fire—not a peace treaty—which has been in place to this day, signed between U.S.-led UN forces, North Korean forces, and Chinese forces; conspicuously not among the parties that signed the treaty were the South Korean forces. Thus, the agreement was more of

A Scarred Nation

From a psychological standpoint, this destruction understandably was something that shaped North Korean culture, mentalities, and worldviews into one of anxiety and fear when it came to America and the outside world in general, and even though North Korea was remarkably rebuilt rapidly and impressively during one of the few true brotherly and inspiring moments of the international socialist movement, with generous aid and on-the-ground assistance coming from the world’s other socialist countries, the sense of vulnerability and fear engendered by the U.S. bombing campaign is still a hallmark of the North Korea’s collective mentality to this day; indeed, hatred of America runs deep in today’s DPRK.

And though North Korea received substantive help from China, the Soviet Union, and other socialist countries, it never allowed itself to be controlled by any of these other powers or to become a pawn. And Kim would not forget that at the beginning of the war, support from both China and Russia came reluctantly. Kim would forge North Korea into a nation that would plot its own path its own way, accepting help while never submitting to foreign control or domination at the hands of far larger powers that had sought, for centuries, to exert their influence and domination over the Korean Peninsula.

While North Korea led South Korea in terms of per capita GNP as late as 1973, today democratic South Korea’s economy dwarfs North Korea’s, whose per capita GDP was less than 4.5% of South Korea’s in 2016 even though North Korea’s population is just under half of South Korea’s; furthermore, even today North Korea is facing mass starvation and may very well be the most oppressive, horrible nations in which to live in the entire world, where anyone can end up imprisoned in Soviet-style gulag labor camps or worse. Photos from space of North Korea at night show a country with virtually no electrical power

Another version of our complicity with the Dear Leader is to be found with his oppression and starvation of his “own” people. It is felt that we cannot just watch them die, so we send food aid in return for an ever-receding prospect of good behavior in respect of the Dear Leader’s nuclear program. The ratchet effect is all one way: Nuclear tests become ever more flagrant and the emaciation of the North Korean people ever more pitiful. We have unwittingly become members of the guard force that patrols the concentration camp that is the northern half of the peninsula.

NASA/ISS

All-in-all, North Koreas’s past history has been a nightmare, one that extends into the present and will certainly extend into the future for at least the foreseeable future.

Old Grudges, New Weapons

Thus, in many ways, the shadow of the bitter, bloody rivalries of the late-nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth-century that consumed East Asia in war through 1953 cast a long shadow over the politics and current crises in the region, especially the North Korean conundrum. It was perhaps fitting that Kim the First, in the weeks before his death in 1994 and after such a long career defined by conflict, desired to improve relations with South Korea. While he had seen and suffered much through occupation, exile, revolution, resistance, and war, the same cannot be said of his disturbingly odd son and successor, Kim Jong-il, or his son and North Korea’s current leader, the deceptively-rotundly-jolly-appearing Kim Jong-un.

After Kim Il-sung’s death in 1994, Kim Jong-il did not take long converting to reality his father’s long-held dream of turning DPRK into a nuclear-weapons power (American leaders throughout the Korean War had hinted at potential nuclear weapons use against North Korea and, bluff or not, these threats had an effect, one that was lasting). In particular, George W. Bush’s first State of the Union (the “axis of evil”) speech in 2002, seems to have really struck fear into the heart of the Kim Jong-il and his regime, pushing them to think then more than ever that the possession of a nuclear weapon would be their only true safeguard against a U.S. attack. Not long after the speech, North Korea removed International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors from its territory and in January, 2003—just months before Bush invaded Iraq and with a clear U.S. military buildup occurring on Iraq’s borders—withdrew from the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT), giving signals as clear as any that it was working on building nuclear bombs, the first of which it finally tested on October 8th, 2006, despite severe warnings from the U.S. and the international community. Since that initial test, five more nuclear tests have been conducted by DPRK, with the largest bomb by far the one that was tested just last month, in early September, and four of which have been conducted by Kim Jong-un, who took over when his father, Kim Jong-il, died late in 2011.

CNN/CNS/NTI

Hand-in-hand with these efforts were efforts to increase North Korea’s missile capability, and the implication was lost on no one: the North Koreans were going to make sure it could hit the U.S. with nuclear missiles as the ultimate deterrent to any military action that the U.S. could take against them. As with the nuclear tests, it is under Kim Jong-Un that the most missile tests have been conducted and the most progress in the technology and capability reached: by 2015 not even four full years into his reign, Kim Jong-Un had tested more strategic missiles than his grandfather (15) and his father (16) had combined in the 28 years of their strategic missile tests; through today, Kim Jong-un has conducted 85 total missile tests including a record 24 in 2016 and another 22 so far this year since President Trump’s inauguration, with North Korea being on pace in 2017 to break the previous 2016 record. 2017 saw the DPRK’s first tests of missiles that could strike the U.S. (the 50 U.S. states, anyway), including, pointedly, a test on July 4th—not coincidentally America’s Independence Day—of North Korea’s first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the Hwasong-14, the first missile which could which could strike the 48-contiguous U.S. states, including the cities of Los Angeles, Chicago, and perhaps even New York. Thus, it’s not only the rhetoric between the unstable Kim and the unstable Trump that has been heating upsince Trump became president. And with a long history of DPRK/ROK border-area incidents (any of which could have quickly escalated an always tense situation into nuclear war), with Kim Jong-un increasingly willing to violently gamble with provocative and violent border actions, and with Trump personally calling for an end to diplomacy, the likelihood of war erupting on the Korean Peninsula is higher today than any time in decades, a time when one misunderstanding can spiral out of control before there is any chance of stopping war.

*****

Reuters/Kevin Lamarque; Reuters/KCNA

Some key points need to be made here, taking all this into account:

1.) China is no silver bullet to solving the North Korea problem, and it does not have a magic wand with which it can control Kim Jong-un or his regime

China probably finds North Korea as frustrating as the United States, probably even more so. DPRK’s extreme self-reliance (

2.) China is definitely not looking to have history repeat itself

China’s current leadership will most certainly not want to repeat the mistakes or results of the Qing Dynasty. China enjoyed a centuries-long relationship with a subservient Korea under undisputed Chinese hegemony until Western powers weakened China to the point where Japan felt comfortable enough to challenge China’s sphere of influence in Korea starting in 1876 and then totally pushing China out in a war with China that left Japan in 1895 occupying the status in relation to Korea that China had occupied for hundreds of years, but with even more direct control and influence. This gave Japan a foothold on continental Asia from which to expand aggressively against China in a devastating war that began in 1931 and merged into WWII, a conflict in which only the Soviet Union more death and devastation absolutely than China. China then lost Taiwan because of U.S. support for the Nationalists who fled the Chinese mainland in the face of victorious Chinese Communists during 1949 in the closing chapter of the Chinese Civil War, and then had to accept a Korean Peninsula partitioned into two less than a decade later, where China only retained major influence over North Korea (and only after tremendous sacrifice) and the United States had a clearly dominant position in South Korea when the ceasefire of 1953 came into place. With its long-view of history, China would see any Western military action in North Korea as a disaster, a lost to its prestige and a stage-setting for further aggression and weakening of China, as was the case far too many times for China’s liking between 1876-1953. It certainly does not help that the U.S. is so strongly allied with Japan, the perpetrator of such much aggression against China from the late nineteenth-century through WWII.

When the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, two of the major neighbors sharing Iraq’s borders—Iran and Syria—did not share the aims of the United States in Iraq and actively worked against the U.S. succeeding in these aims. If the U.S. attacks North Korea without the support of China and/or Russia (hell, even U.S. ally South Korea is warning the U.S. not to strike North Korea), this dramatically reduces that the outcome in the long-running will resemble what American leaders hope it will. Even this year, Chinese trade with North Korea increased dramatically in the first half of 2017, while Russia is actively

3.) North Korea is probably less responsive to international pressure than any other nation on Earth

As already mentioned, DPRK embodies an extreme form of self-reliance () that is deep-seated, meaning it has been and is prepared to go it alone with little or no help from the outside world. Its leadership uses the humanitarian concerns others have for the welfare of its own people to gain concessions from those and uses the threat of war and chaos to get what it needs from a nervous China and others eager to not rock the boat. Its regime cares not about the welfare of its own people, only its own survival, and has glorified itself and brainwashed its own isolated people from near-birth to hate America to such a degree that many will genuinely gladly sacrifice themselves in to preserve a leadership that treats them as mere resources to be utilized. At best, North Korea will respond far less than other countries to conventional methods of exerting pressure, at worst, not at all in a helpful way. This makes dealing with the nation as an adversary miserable, forcing foreign leaders to choose between risky and ineffective diplomacy and catastrophic war.

North Korea’s entire history has been defined by its resistance to foreign domination (whether imperialism or colonialism) and it has only bent to foreign powers when forced and after great cost and sacrifice; as of now, there is a long way to go before Kim and North Korea will simply bow to the Trump Administration’s demands.

This means there is little room for incompetence or error, two things at which the Trump Administration unfortunately excels. As of now, it is incredulously and unjustifiably undermining the very Iran nuclear agreement (against which there is no logical argument, as I have noted) reached between Iran, the U.S., and other the major world powers only a few years ago, destroying America’s own credibility as a nuclear negotiator at the precise moment when it needs to convince North Korea that the U.S. is a credible negotiating partner, destroying most of whatever hope exists that North Korea would trust any new nuclear agreement the U.S. would offer or abide by it if an agreement were to be made.

4.) A terrible status quo is not always the worst option

The status quo may seem bad, but as many people who understand the current standoff have warned, open war against North Korea—which has the world’s fourth-largest military—would be an unimaginable horror compared to any recent conflict, a bloodbath of a scale not seen anywhere in decades that would kill tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands or perhaps millions in just days or weeks and would likely see Seoul, South Korea’s capital and the world’s fourth-largest city, obliterated… And that doesn’t even get into the fact that South Korea is currently the world’s 11th-largest economy and, of course, this does not even get into potential damage to Japan, China, Russia, or other nations that may be drawn into the conflict.

And oh, we haven’t even mentioned the use of nuclear weapons. We have never seen a military attempt by a foreign nation to disarm the nuclear capabilities of a nuclear-weapons power. Let’s hope we never do.

****

When it comes to North Korea, the history is a nightmare, the present is a nightmare, and the future is a nightmare, but even that does not mean that the nightmare cannot be mitigated, its worst outcomes prevented, and improvements made. President Trump and anyone now advising him that doesn’t consider the above history and points will be doing Americans and Koreans both an unforgivable disservice. Terrifyingly, at this point, the fate of millions of people in one of the world’s worst historical flashpoints rests with the decisions of Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un. If anyone is comforted by that thought, that, too, is a nightmare.

© 2017 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

See author’s Amazon eBooks here!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here!

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter (you can follow him there at @bfry1981). If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!