Despair today can give way to hope tomorrow and hope can give way to triumph even later, as it did in Berlin in 1948-1949

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981) August 25, 2021 (updated August 26 to discuss the terrorist attacks near the airport); see related podcast The Real Context News Podcast #7: Col. Steve Miska, U.S. Army (Ret.) on the U.S. Withdrawal & Our Duty to Our Afghan Allies and related articles 9/11, Afghanistan, and the “War on Terror”: The Long View (& the Tragic One) and America’s History of Failure in Unconventional and Asymmetric Warfare Is Instructive for Our War with the Coronavirus

SILVER SPRING—The situation looked grim. Wholly surrounded by a grim, much-feared, terror-inducing-and-utilizing hostile power and deep in the territory that power’s forces controlled, the U.S. military and its allies found itself with few options and many thousands of civilians in its care, dependent on U.S. assistance not just for aid but for survival. The crisis had developed amidst a massive regional military withdrawal, with the current American presidential administration finding itself in shock, surprised that its foe would be in the position it was in at this time in a way that caught America and its allies at a distinct disadvantage and clearly without plans in motion that anticipated the current debacle. The key U.S. planners and decision-makers had clearly underestimated the boldness of their foe and the speed with which it would act and succeed; earlier, more urgent warnings were not heeded in full. And while the U.S. and this foe had not and were not engaged in direct hostilities in this time period, the tension was suffocating and combat seemed ready to erupt at any provocation. Civilians were not so lucky and had found themselves targeted and caught in the standoff, their future uncertain and looking grim. Would their American occupiers-turned protectors stand by them? Or would they be abandoned to the cruel depredations of a sinister foe driven by an extremist ideology?

This description could easily apply to the situation today faced by U.S. President Joe Biden at Afghanistan’s Hamid Karzai International Airport on the outskirt’s Kabul, the country’s capital city, describing the situation of the U.S., its military allies, and Afghan civilians in an island of U.S. control amidst a sea of terrorist Taliban-controlled territory, but it would just as aptly describe the situation faced in June 1948 by one of Biden’s predecessors, Harry Truman, in Germany’s divided capital of Berlin, with West Berlin an island of U.S., British, and French control amidst a sea of Communist Soviet-controlled territory.

Obviously, there are key differences: the Soviet Union and the Taliban are hardly equivalents, and we had been allied to one and in a longstanding war with another; Germany is not Afghanistan, whether culturally or in its location; 1948 is not 2021; in one situation we were bringing in supplies to save at-risk civilians and to maintain our own position and in the other, we are trying to get people out from a position we are not trying to maintain after this evacuation; and the overall geopolitics leading to each are quite different in many respects.

Nevertheless, the tactical similarities are striking and deserve examination.

Two Dire Situations

Since the end of WWII, Germany had been divided by the victorious Allies into a Soviet zone in the east and American, British, and French zone in the West, with Germany’s capital of Berlin also similarly divided into four occupation zones: the Soviets in a large zone in what would be known as East Berlin, and the American, British, and French zones in what would be known as West Berlin. Some of the major issues that helped set up the possibility of the Berlin crisis arose much earlier, from oversights in planning and negotiations going all the way back to during WWII itself, under the previous presidential administration. And it was in the fall of 1947 that Gen. Lucius Clay, the U.S. Military Governor for Germany, warned that the Soviets might go as far as to force the West out of Berlin, but, as historian Wilson Miscamble noted, “no precautions were taken nor were contingency plans made in Washington.” When the U.S. Army’s Planning and Operations (P&O) Division put together in January 1948 a study of options in the face of Soviet aggression, its recommendation in the event of a full blockade was to try to remain in the city as long as supply would allow but to eventually evacuate. Gen. Clay even warned on March 5, 1948, of the “dramatic suddenness” with which war could come, yet this sparked not attempts to shore up a weak U.S. position but only evacuations of family members of American staff and a discussion in the Army section of the Pentagon of withdrawing from Berlin. The Secretary of the Army did not think the U.S. could stay if the Soviets applied significant pressure; Army Chief of Staff Omar Bradly in April echoed this with a lack of confidence the U.S. was prepared to fight to stay in Berlin, and had even that month suggested withdrawing from Berlin in response to a temporary crisis then over Soviet inspections of U.S. trains supplying Berlin. The French wanted to leave Berlin entirely.

Even Gen. Clay, though, did not think that the Soviets would engage in a full blockade for fear of hurting their standing among the German people. The leadership of both the Army and the State Department did not feel a Soviet blockade was likely, either, while the CIA on May 12 only warned of “further gradual tightening of Soviet restrictions” and even expressed as late as June 17 confidence that the Soviets wanted to improve relations with the West. Other top officials thought the Soviets would apply pressure on the West to leave Berlin only over time and gradually. Truman himself was focused on a tight Democratic primary, 1948 being a presidential election year.

Unsure if it would even stay in Berlin, the U.S. did not anticipate nor act to deter the Soviets from enacting a full blockade. Thus, Truman and his team were caught off-guard after the Soviets imposed a full blockade on the Western sectors of Berlin late on the night of June 23, just a week after the CIA released an intelligence estimate that in no way predicted anything like a full blockade in a week. Already low on supplies in a Berlin that was still mostly bombed-out ruins, the Germans living in the Western zones would start suffering in a few days, seriously so within two weeks, without access to new supplies. Military and civilian planners, intelligence officials, and the president himself had failed to anticipate what was happening, and on June 24, the U.S., its allies, and the civilians under its control woke up and found themselves in dire straits, facing an entirely predictable but imminently looming disaster with very few options and the possibility of miscalculation or war erupting from even one wrong move tremendous.

This is remarkably similar to the situation the Biden Administration, its allies, and those civilians depending on the U.S. found themselves on August 14. The Biden Administration had similar warnings that the security situation was dire, that preparations should be accelerated, and that Afghan security forces were not likely to last long and that government could collapse quickly, though, to quote U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of staff Gen. Mark Milley, “there was nothing…that indicated a collapse of this army and this government [Afghan] in eleven days” and it was blindsided like the Truman Administration was in 1948. Those on Biden’s team, too, had to feel out and develop their approach and see how their foe would respond, and have made progress even with a lack of clarity and much confusion.

Yet the awful precariousness and desperation of the situation in Berlin on June 24, 1948, the miscalculations and missteps in the run-up to that moment, the terror of Berliners in Western zones, are barely remembered today; instead, the wildly successful outcome of the Truman Administration’s response, the bravery of American pilots, and the logistical miracle of the Berlin Airlift are remembered much more than the Berlin Blockade.

Here, history can be both instructive and provide hope.

Feeling through the Dark in Berlin

Truman’s top staff, even after the Berlin Airlift began in full on June 26th, did not know how things would unfold, did not know what U.S. policy would be over time, did not know what they would do in the event of a Soviet attack, remained divided on Berlin, and were often just trying their best to react to rapidly unfolding events. The U.S., Britain, and France were divided with each other on Berlin policy, too. Truman’s top advisors were still deciding if they wanted to stay in Berlin or leave when Truman communicated his (apparently “tentative” and “provisional”) decision (to stay), without much discussion, on June 28, but debate on this within his team would continue for months and Truman’s own tentative nature of the firm short-term commitment he made indicated he wanted to see how things would play out over time.

Over the coming weeks, Truman struck a precarious balance between acting forcefully to protect Americans, Western allies, and German civilians in West Berlin while also trying to avoid provoking the wily, nefarious, hard-to-predict Soviets or sparking military escalation. The Airlift was even seen as a compromise, risk-averse, time-buying, temporary measure—one that lacked support from key U.S. military leaders—until late July, when Truman decided to make it a longer-standing policy; before then, the situation was characterized by uncertainty and anxiety, with Truman’s public and private statements offering some clarity for various present moments but not on general policy, leaving anything save the near-term future ambiguous. And for some time—until January 1949—the Airlift fell short of what was needed to properly supply Berlin (one can only imagine how today’s media would decry this as a “failure” and focus on the shortages in Berlin, where households that winter of 1948-1949 had only one hour of electricity per day each).

It is important to note this suffering and the setbacks, and while the Berlin Airlift was messy, uncertain, and ad hoc, in the end, it worked out incredibly well for the U.S., its allies, and West Berliners, with the Berliners themselves particularly determined to hold out. In hindsight especially, in a situation that was extremely tense that could serve as a catalyst for a full-blown conventional or even a nuclear war, instead of committing outright to high-risk policies, Truman allowing things to develop and to react as the developments occurred proved to be the safer, sounder middle course, despite the desire of many—including some of Truman’s top advisors—for firm positions, clear answers, and long-term clarity.

The Real Achievement in Kabul

Today, the press should not expect Biden to have all the answers, either; he, too, is responding to a rapidly developing, precarious, and uncertain situation and has to engage a wily, nefarious, hard-to-predict Taliban; he, like Truman before him, wants to avoid any military escalation. But the Biden Administration and its allies still have options, with thousands of troops and their highest level of focus and energy bearing down upon the situation in Kabul as the Kabul Airlift is in full swing.

Yet much of the media—which barely, and I mean barely, covered Afghanistan in recent years)—ABC, NBC, and CBS devoted a collective measly five minutes to Afghanistan in all of 2020 on their main evening news broadcasts out of over 14,000 minutes of those programs’ total news coverage)—is pronouncing Biden’s withdrawal execution a failure (“total,” “complete”), inviting many of the people who botched America’s foray into Afghanistan over two decades, even those who negotiated or supported the terrible Trump Administration’s withdrawal agreement with the Taliban to hypocritically chime in along the same lines (a notable exception is Trump’s own former National Security Advisor, Gen. H.R. McMaster, who likens the deal to the Munich appeasement of Hitler).

While it is undeniable that there were disastrous tactical calculations and mistakes made during the past weeks and months, the media is mainly trapped in the mentality of August 14, when things seemed disastrous and any serious adjustments, fixes, or mitigating responses from the Biden Administration were not apparent. Back in 1948, the press basically had daily print editions and radio/TV broadcasts at most few times a day, no twenty-four-hour news coverage, no mobile phones with video cameras, no Twitter, no Internet. Coverage was less focused on details and anecdotes but on putting together a bigger picture, a task that I have repeatedly noted our current media struggles to accomplish.

And that current press is missing the massive, increasing success of the Kabul Airlift.

Some numbers that do not lie: in the eleven days from fall of Kabul to the Taliban on August 14-15 through August 24, the U.S.-led operation has evacuated some 82,300 people—mostly Afghans—from Hamid Karzai International Airport, including:

- some 7,800 on Saturday

- an incredible 10,400 by the U.S. military and 5,900 by coalition aircraft on Sunday (over 16,000 in one day and well over 27,000 in the two-and-a-half days from mid-Friday through Sunday)

- a further, even more staggering 21,600 people on Monday (12,700 on U.S. military flights and 8,900 on coalition flights)

- a similarly massive 19,000 on Tuesday (11,200 on U.S. military flights and 7,800 by coalition craft)

- the four-and-a-half-day total from mid-Friday through Tuesday is close to 68,000 people (40,600 from Monday-Tuesday alone)

- including those evacuated through the airport since late July, the operation has flown out from the airport some 87,900 since late July

And all this has been accomplished with zero U.S. casualties.* (see 8/26 update at end)

Let that sink in. This is a remarkable achievement, especially considering the extreme circumstances and the rapid adjustments and moves required to make this happen, for which Biden, his team, and those operating on the ground in Kabul deserve much credit.

If we can meet this accelerated pace from the last seventy-two hours or even close over the next week, and assuming much of the final day or two would have to be prioritized for removing U.S. troops and coalition military and diplomatic forces, that would be roughly 70,000 to perhaps as many as 160,000 or more additional people evacuated by August 31, the just-yesterday reaffirmed apparent (but still apparently flexible) deadline chosen by Biden. That would be roughly 120,000-220,000 total, but this presumes safe and free passage to the airport for Afghans trying to leave and recent developments have severely complicated this issue (more on that later). Still, this has the potential to be one of the most remarkable humanitarian logistical feats since the Berlin Airlift (in many ways, it already is), and the media should at least recognize this hopeful possibility alongside the peril of a far worse possible outcome; if the possibility of ISIS-affiliate (ISIS Khorasan, or ISIS-K) attacks deserve being reported (and it does), then so, too, does the possibility of successfully getting out 100,000 to 200,000 or more people fleeing the Taliban, especially when the evacuations have been impressive, quickly increasing, and successful thus far.

Soviet Lessons for the Taliban

The Taliban, too, can also learn from history: the Soviet leadership, even under a man like Joseph Stalin who reigned through terror, realized that to interfere or attack these humanitarian flights would be a public relations disaster worse in scale than the circumstances they were imposing on Americans, their allies, and German civilians in West Berlin. The Soviets were untrustworthy, extremists, and not afraid to use brutal violence on a massive scale. And yet, they knew they had to some degree win hearts and minds and not appear to be a terrible, bad-faith actor on the world stage; they knew they had to govern in the territory they had newly acquired and, still recovering from a long, brutal war, they did not want to alienate the international community.

Understandably, then, the Soviets in the end decided it was in their own interests not to be seen stopping the Berlin Airlift and to eventually, eleven months later, end the Berlin Blockade on May 12, 1949.

The U.S.-led Western allies were able to leverage their superior economic might to impose their own blockade on Soviet-occupied eastern Germany, a major factor in the Soviet decision to relent in their blockade of Berlin. This type of leverage is something today’s U.S.-led Western allies could easily exert if the Taliban interfere with the Kabul Airlift; the Taliban’s leaders—desperate for acceptance, recognition, and aid from the very institutions run and dominated by the U.S. and its allies—know this and know their requests for the West to engage with them, maintain and increase aid programs, and further economic ties with an Afghanistan under their control will fall on deaf ears should they not allow the Kabul Airlift to proceed and or even engage in violence against the operation or those trying to reach it.

Today’s geopolitical situation is actually surprisingly similar, then, to 1948 in a few crucial aspects: facing a stark imbalance similar to that faced by the Soviet Union in 1948, the Taliban today surround the Western position in question and are in a far superior military position locally even as it is in a far weaker position economically and diplomatically. Both the U.S. today knows and in 1948 knew that the eyes of the world are and were on the crisis, that global public opinion is and was with their mission, and that judgment of their enemies would be harsh if those enemies thwarted that mission. Today, the Taliban is capable of bluster and threats much like the Soviets, to be sure, but also like the Soviets with the Berlin Airlift and their occupation zone in Germany, the leaders of Taliban will find their movement’s position on the ground and ability to work with the world to rebuild the Afghanistan they just have taken over will be better off with the Kabul Airlift succeeding than with them derailing it.

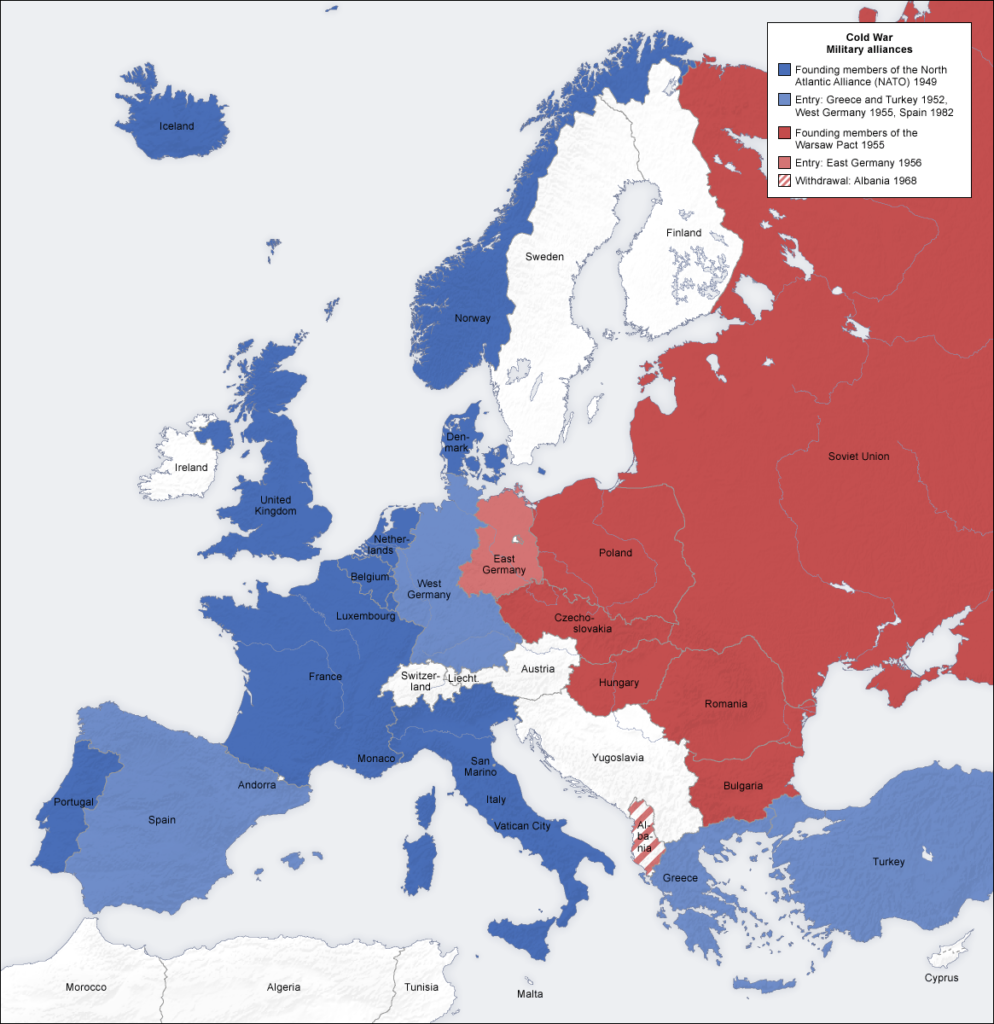

It was hardly a love-fest between the Soviets and the West in a divided Germany after the Berlin Airlift—not long after, West and East Germany, NATO and the Warsaw Pact, were created—but peace has been in place in Germany ever since, all of Germany saw a massive recovery from WWII, and WWIII was averted. Both the West and Soviets were able to maintain their positions, but, in the end, though it took decades, the repression of the Soviets and failure of their imposed system resulted in a lack of popular support and a desire and eventual reality of East Germans reuniting with West Germany under the free and democratic West German system, not the repressive Soviet model running on extremist ideology.

The Taliban, far less powerful in 2021 in Afghanistan than the Soviets were in Germany in 1948, should also take heed from this lesson if it hopes to avoid resistance, revolution, and overthrow. And, unlike Truman in 1948, Biden in 2021 is not even contemplating staying, so there is even less incentive for the Taliban than for the Soviets to interfere or attack the airlift operation, which even the Soviets did not do back then.

Despair and Hope in a Dance

The media is right to point out the mistakes made by Biden and his team in the past weeks and months, and if the Biden Administration fails to evacuate a significant number of Americans or Afghan allies who were not stuck behind Taliban lines in the weeks and months before the fall of Kabul, that will still be a disgrace, each individual left behind a failure of the Administration in and of itself. But the press should also recognize the remarkable achievement that the Kabul Airlift is becoming and will hopefully firmly be remembered as—in addition to recognizing the clear parallels to the Berlin Airlift—provided our leaders see this mission through to a proper completion.

And that is where things get a lot more complicated: it is altogether too easy to have a sinking feeling that we will fall far short of evacuating everyone we should be able to get out, leaving tens of thousands behind, that something really bad will happen. It is easy to feel despair when you read yesterday that the Taliban is announcing a policy of blocking Afghans from the airport road, a policy that, if enforced robustly, will make it extremely difficult to extract many more Afghans; they are legitimately worried about a “brain drain,” but one cannot help worry that this stems at least as much from a desire to keep those who helped us from escaping, to mete out their barbaric sense of justice not just on our allies but also their families. Should this happen, the grave earlier missteps of the Biden Administration will haunt Biden, the Kabul Airlift, and the whole Afghanistan war, should haunt all Americans and the world.

And yet, there are reasons to still hope even with the latest developments. It is easy to also feel a sense of American pride in how many tens of thousands of people we have gotten out so far, in how quickly we ramped up evacuations in just the past few days. Unimpeded, there is so much more we can still do, so many more we can save, with our evacuation operation running amazingly smoothly and hitting a peak. And there is apparently broad bipartisan support in Congress for extending the mission if necessary to get as many of our Afghan allies out as we can.

Set against this will to get the job done, there is now also a very real, breaking, specific, imminent threat from the aforementioned local ISIS affiliate, which intelligence indicates is seeking to attack civilians—American and Afghan—clustered outside the airport gates.

Knowing that just this past Monday our own CIA chief William Burns met in person in Kabul with de facto Taliban leader Abdul Ghani Baradar (released from a Pakistani prison at the strong urging of the Trump Administration in 2018), there is clearly high-level intelligence sharing going on between the U.S. and the Taliban, a mortal enemy of ISIS. In this context, it seems even more understandable that the Taliban would want to avoid having chaotic mobs of many thousands of Afghans interspersed with foreign nationals, including Americans, clogging the airport road and the areas outside the airport gates making an all-too-tempting target for ISIS suicide bombers, mortars, or any other manner of deadly attacks. The U.S., obviously, wants to avoid this, too. Ending the war with such scenes of terrorism and carnage, with people packed so tightly that casualties would undoubtedly be high, and putting Afghan civilians, American civilians, and American soldiers at such risk, would be irresponsible. Neither the Taliban nor the U.S. wants ISIS attacks to succeed, so maybe most of the reason for the Taliban banning Afghans from trying to run the gauntlet of the airport road, especially after the chaos and crushing deaths there from earlier, but it would be irresponsible to not consider it likely that they also want to just keep U.S. allies from escaping their sick sense of justice.

Still, given this context of intelligence sharing and of the imminent ISIS action, and give the obvious reality that the U.S. is applying constant diplomatic pressure, that negotiations with the Taliban are constant and ongoing, that Biden did vow to get all the Americans and SIVs and their dependents out, that the U.S. (as discussed) has tremendous leverage over the Taliban, that a tremendous amount of pressure will be placed on the Taliban to allow the right Afghans safe passage to the airport and in a robust flow once security conditions allow, and that Biden himself yesterday said, announcing his intention to adhere to the August 31 deadline, that keeping to that deadline

depends upon the Taliban continuing to cooperate and allow access to the airport for those who were transport-—we’re transporting out and no disruptions to our operations. In addition, I’ve asked the Pentagon and the State Department for contingency plans to adjust the timetable should that become necessary. I’m determined to ensure that we complete our mission — this mission.

This gives me a lot of hope, even if security dictates a winding down of the U.S. military operation, that Biden, as a man of history and with the Berlin Airlift as inspiration, really will come up with one or more workable alternative if that is what is necessary to, as he said, “complete the mission.” Nothing is certain yet other than what has already transpired—the bad and the ugly, but also the good. We should all feel a sense of dread but also cautious hope, as the Biden Administration’s efforts, even after severe mistakes and setbacks and in sometimes anarchic and frenzied conditions filled with danger and uncertainty, have gotten over well over 82,000 people out in eleven days (that number is sure to grow) with zero U.S. casualties (that number is not sure to grow).* (see 8/26 update at end)

To paraphrase the military historian Daniel Harrington, the very real confusion, lack of clarity, and hesitation during the Berlin Blockade are not among what we remember today; the symbolism of American defiance and determination resulting in a triumph against the odds in the Berlin Airlift are. With so much yet to unfold, it is still quite possible that the Kabul Airlift may end well and succeed in evacuating a tremendous amount of people mostly without incident even after the initial disastrous missteps, that the U.S. might succeed in withdrawing with honor and staying true to most of our citizens and allies.

One other major legacy of the 1948-49 Berlin Airlift: that German troops are currently serving and fighting alongside U.S. troops as NATO partners in Afghanistan deployed to the airport at the heart of the current 2021 Kabul Airlift. Even with all the justified dread, this fact, too, can inspire and remind us all that there is still a real chance for this operation to go down in history as a resounding success. No one—not those in the media, not us, not President Biden’s allies, not his political enemies—should prematurely conclude that this mission is a failure or a success yet; time remains, with reasons to fear but also reasons to hope. As Biden is fond of quoting the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, let me leave you with his words:

History says / Don’t hope on this side of the grave / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme.

UPDATE: 8/26 2:30 PM U.S. EST: The awful carnage we were all hoping would be avoided has transpired in what is apparently an ISIS-K attack that has killed and wounded dozens of Afghans and Americans: at least sixty afghans and four U.S. Marines are dead, many people injured. This carnage is heartbreaking, and reminds us that the theme there really is despair dancing with hope. Yet how this mission will end remains to be seen: there is still the possibility for the mission to continue and evolve and move on to new phases, to still get many, many thousands more out, to do so with minimal casualties, to finish by and large as a historic success. One day, one attack can and will not define the overall character of the mission; the mission in its totality and how we finish it, though, will, and this still remains to be seen. Let us hope for the best and dismiss those making facile conclusions about an ongoing mission.

© 2021 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

See related podcast The Real Context News Podcast #7: Col. Steve Miska, U.S. Army (Ret.) on the U.S. Withdrawal & Our Duty to Our Afghan Allies and related article America’s History of Failure in Unconventional and Asymmetric Warfare Is Instructive for Our War with the Coronavirus

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!