Trump’s flirtatious waltz with hints and threats of political violence cannot be ignored and should not be underestimated. Apart from echoing some of America’s own worst episodes in the South after the Civil War, such dangerous dancing brings to mind the lessons of the ancient Roman Republic, and how, after centuries of peaceful politics and peaceful transitions of power, one horrible incident of political violence begat many others in subsequent decades, culminating in civil war and the death of Rome’s democratic Republic; the Roman Republic far outlasted America’s republic (so far) even before that violence began, so anyone who thinks the United States is immune from a similar fate is suffering from a hubris that ignores history and human nature and the terrible consequences of precedent-shattering political violence.

Originally published on LinkedIn Pulse October 23, 2016

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981) October 23rd, 2016 (UPDATED 10/26 to further discuss race & politics in America)

AP Photo/ Evan Vucci

Silvestre David Mirys (1742-1810) – Figures de l’histoire de la république romaine accompagnées d’un précis historique Plate 127: Gaius Gracchus, tribune of the people, presiding over the Plebeian Council

AMMAN — We have already had people being punched at Trump rallies, clashes with police, a mini-riot by Bernie Sanders fans inside a Democratic state convention in Nevada and that Bernie Sanders himself all but seemed to fully excuse at the time, and now, a firebombing of a Republican HQ in a county in North Carolina.

Trump Fanning Flames of Unrest

In the midst of all this Trump has convinced many of his supporters that there is a global top-to-bottom conspiracy to cheat him of the election and that this election—which is only just beginning—is already rigged against him and, by extension, his supporters (never mind how astronomically impossible that such a rigging as he describes it would actually be happening). In fact, he has been so successful at this that almost 70% of Republicans believe Clinton can only win by cheating and half of Republicans would refuse to accept her as president. At the final debate, he even raised serious doubts about whether he would accept the results of the election, putting in jeopardy an unbroken tradition going back to George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson in 1796-1797 of a peaceful transfer of power between presidents and the loser accepting the outcome, even in hotly disputed or controversial elections like those in 1800, 1824, 1876, 1888, 1960, and 2000. The day after the debate, he doubled down on this rhetoric and failed to alleviate the concerns he had raised the previous night, joking(?)/stating(?) that he would accept the election results “if I win.”

If that wasn’t bad enough, Trump has been saying that there is a need for volunteers to “watch” polling places to make sure there is no “voter fraud” and is encouraging his partisan supporters to undertake this task that is supposed to be bi-partisan and non-partisan, and he and his surrogates are specifically suggesting monitoring of certain urban (code word for heavily-black) areas. In places like Texas and Florida, over 80% of Republicans think that voter fraud is a major problem, with zero evidence to support this but ample rhetoric from Team Trump and the GOP trumping reality yet again with their misinformation and disinformation.

Yes, angry, white, possibly-well-armed Trump supporters—people who number in the tens of millions, who are passionately convinced Trump is right and should be president, who are now talking of assassination, revolution, and coups should Hillary be elected—are already talking about descending upon minority-heavy polling areas on Election Day in an effort to make sure such shifty (in their view) minorities, prone to election malfeasance (in their view), don’t try anything funny; and yes, many of these people own guns and will show up openly armed because in many locations they will be allowed to do so, and yes, out of Trump’s tens of millions of devotees, we can certainly expect many thousands to show up as he has asked them to, and to show up in this manner, at polling places on November 8th, something that will more likely than not lead to trouble, especially in America’s increasingly racially-tense atmosphere. For those who don’t know their history, this was how white Southerners intimidated and usually prevented freed slaves and African-Americans from voting, from Reconstruction all the way through the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Never mind that Republican and Democratic officials at all levels, including local election officials from both parties, have dismissed as absurd the idea that the election is rigged or that any local polling places are going to be compromised or part of a voter fraud scheme. Never mind that voter fraud is practically non-existent, and that campaigns claiming to want to deal with voter fraud are more about denying minorities the ability to vote than anything else (for actual voter fraud on a staggering scale, see Vladimir Putin’s Russia).

Unfortunately, this election is a moment of terror, and for many Latinos, Muslims, African-Americans, and others, it must on a personal level be a terror that far exceeds any emotions I have on the issue as a white male. I am not sure if state and local authorities are up to the challenge, are aware of what could really happen in a realistic worst-case scenario here: thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, maybe more, of Trump supporters, many who could be armed, are going to be seeking to either harass and intimidate people they falsely believe, with no evidence, are committing voter fraud—picking people out by skin color almost certainly—or maybe even just be flat-out seeking to disrupt voting in liberal precincts in an effort to suppress minority votes (again, nothing new in American history and something that has happened in living memory). Violence, riots, voter disenfranchisement—all are in the realm of realistic possibility on Election Day now. We have already recently seen what crowds and individuals can do when animated by racial animus, crowds on different sides of the debate, from crowds of mainly angry black citizens to crowds of paranoid police in a cycle that seems to have been reignited since Ferguson after decades of near dormancy.

I am not being hyperbolic. I am not being paranoid. And Donald Trump’s rhetoric to millions of his supporters that the election is being stolen from them and that they need to go “watch” polling places is not abating or going away; nothing inherent in American society makes it immune to internal violence or breakdowns of law and order. This is the reality mere weeks before Election Day, and I hope federal, state, and local law enforcement are planning accordingly; some are aware of these dire possibilities, but whether they are given the resources to deal with this possibility, or if their plans are competent, remains to be seen.

Jeff Swensen/Getty Images

Lesson’s From Ancient Roman Politics

Is this a Rubicon moment for America?

HBO/Rome

Not really a Rubicon moment, but more of a Gracchi moment.

By a Rubicon moment, I am using a colloquialism of a point-of-no-return when a drastic action is taken. This word Rubicon in this case refers to the moment in 49 B.C.E., when Julius Caesar crossed south over the Rubicon River with his army, a river which marked the boundary between a province where his army was authorized to operate and Roman Italy proper where it was not after the Senate left him a choice between what would have been an unjust prosecution at the hands of his political rivals on one hand and starting a civil war (only the second since the founding of the Roman Republic in 509. B.C.E. but also the Republic’s last, the Republic itself not surviving this final round) on the other. But the Roman Civil War that began in 49 B.C.E. was merely the culmination of a number of awful trends that started in 133. B.C.E.

We are clearly not at a Rubicon moment in America, the second most successful republic in history after Rome’s ancient one.

But, still terrifyingly, we may be approaching a 133 moment: the snowball which starts an avalanche.

What happened in 133? After the Romans’s version of the Revolutionary War that overthrew the rule of kings in 509. B.C.E., apart from some minor incidents early in Rome’s history as a Republic that are more legendary than anything certain, Rome essentially had three-and-a-half centuries worth of relatively stable, democratic republican government; political violence was a minimum or nonexistent, and nothing like an officially directed assassination, civil war, or use of the military to settle internal political disputes ever occurred. Sure, its democratic qualities evolved over time and like even modern democracies there were factors that favored elites, much like in the United States, which did not even begin with allowing all white adult men to vote, let alone blacks or women. In fact, some states in America did not even have popular votes in the first presidential election, during which all had property-owning requirements for voting for president if there were popular votes at all, requirements that were only gradually abolished in the coming decades, starting with New Hampshire in 1792, though a greater degree of democracy was practiced at the state and local levels. Still, it was not until 1856 that all white male citizens in America were finally able to vote regardless of property ownership, and that was only 14 years before freed slaves and all adult males were given the right to vote with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.

By 133 B.C.E., common Romans had long had an important role in selection of the Republic’s senior magistrates, and, in particular, there was one office that from Rome’s earliest days was created to be a sacred, inviolable protector of the people: the tribunate. The tribunes of the plebs (short for plebeians, the members of the lower class) were elected each year and could prosecute any other government official for abuse of power, as well as veto any government act, and introduce legislation of their own accord and even bypass the Roman Senate and go directly to the people’s assemblies to pass their programs, even though this was against unofficial custom. The most powerful political officeholders were the two annually elected chief executives, the consuls (think of America having to co-equal presidents elected every year), who presided over the Senate and had more power than any other elected officials. These two offices are important to understand when looking at the events from 133 on, and the below chart I created gives a good idea of how the Roman government operated:

It is also important to understand the seismic changes going on in Roman society at this period in its history. After well over a century of on-and-off-again conflict, Rome had finally succeeded in literally wiping its greatest rival Carthage off the map in 146 B.C.E., a Carthage that was just a shadow of its former self long before that final last gasp. As a result of Rome’s successful wars, a huge influx of slaves into Roman lands meant that many small freeholding farmers were put out of business as wealthy elites created huge estates run by slave labor and greedily gobbled up the land of small farmers. Rome had gone from a primarily small-farming Republic to an overseas empire dominated by large slave-owning landowners. Roman cities swelled with newly landless urban poor, many of them veterans and their descendants, veterans who had been unable to maintain their family farms fighting for years at a time in long, overseas wars; Rome’s elites were clearly leaving the concerns of the poor masses unattended.

While Carthage and others were a threat, the different classes of Roman society were forced to work together in a spirit of pragmatism to fend off so many existential foes (this is similar to the moderation and bipartisanship exhibited in American politics during its Cold War with the Soviet Union). But a new political culture of selfishness, greed, and ambition, each rising to new heights, was emerging in Rome with the destruction of Carthage. There was just so much unprecedented power to be had that the stakes of and how far people were willing to go in politics had reached new levels; competition became much stiffer as a few of the most powerful elite families were drowning out the other lower aristocrats. Corruption grew by leaps and bounds as a result, and the tradition of the abstemious, stoic, small farmer ideal had become just that, that ideal further from being a reality than at any time in Roman history and that gap only about to get worse. In fact, it got so bad that the governing Romans began to be worried that the military was going to lose its base of recruitment, at that point limited to landowners. And decades later in the first century B.C.E., the interests of large multinational corporations called publicani helped to put so much money into the political system that Roman senators could not be trusted to fight for the people over their own and publicani pocketbooks.

Even at the time, many contemporary Romans of the first century B.C.E. were aware that the post-Carthage culture of Roman elites of greed, corruption, ambition, scorched-earth politics, and extreme partisanship bieing placed over both the common good and a spirit of compromise; this new culture was at the heart of the disease which led to the death of the Republic (nominally in 27 B.C.E. but really in 49 B.C.E.); in the words of the ancient Roman historian Sallust, it was peacetime, not war, which undid Rome:

“Fear of a foreign enemy preserved good political practices. But when that fear was no longer on their minds, and arrogance, attitudes that prosperity took over. the tranquility they had longed for in difficult times proved, when they got it, to be more cruel and bitter than adversity. For the aristocracy twisted their ‘dignity’ and the people twisted ‘liberty’ towards their desires; every man acted on his own behalf, stealing, robbing, plundering. In this all political life was torn apart between two parties, and the Republic, which had been our common ground, was mutilated…self-indulgence and arrogance, attitudes that prosperity loves, took over. As a result the tranquility they had longed for in difficult times proved, when they got it, to be more cruel and bitter than adversity. For the aristocracy twisted their ‘dignity’ and the people twisted ‘liberty’ towards their desires; every man acted on his own behalf, stealing, robbing, plundering. In this way all political life was torn apart between two parties, and the Republic, which had been our common ground, was mutilated…

And so, joined with power, greed without moderation or measure invaded, polluted, and devastated everything, considered nothing valuable or sacred, until it brought about its own collapse.” ( The Jurgurthine War 41.1-10)

To place Rome’s rapid rise in perspective, consider that by 133, Rome had gone in living memory from surviving multiple existential threats from Carthaginians, Gauls, and Greeks, had gone from just controlling Italy, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, and some of Spain’s east coast to dominating nearly the entire Mediterranean either directly or indirectly; specifically, 133 was year of remarkable fortune for Rome: the late King of Pergamum—a wealthy Greek kingdom in what is now Turkey un western Asian Turkey—had actually willed his entire domain to the Roman Republic, and it passed to Rome upon his death in 133. Rome had already grown dramatically in size, wealth, and power, adding most of northern Italy, all of Greece, most of Spain, most of Southern France, and much of Carthage’s old African holdings to its domains. But Rome’s Western territories were far less developed than the older, fabulously wealthy cities and kingdoms of the East. The addition of the Asian Kingdom of Pergamum to the Republic’s empire had Roman businessman salivating as the prospect of the profits from the riches of doing business in the Asian east.

The Gracchi and Rome’s Descent Into Political Violence

Jean-Baptiste Claude Eugène Guillaume- The Gracchi

The year this remarkable gift to Rome came about, one of the tribunes of the plebs that had won election for that year of 133 was an ambitious but high-minded would-be reformer: Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, hailing from two very famous and elite Roman bloodlines. A champion of the masses, the Greco-Roman historian Plutarch has GRacchus giving a passionate speech in which he lamented that while the

“wild beasts of Italy have their dens and holes to lurk in…the men who fight and die for our country enjoy the common air and light and nothing else…The truth is that they fight and die to protect the wealth and luxury of others. They are called the masters of the world, but they do not possess a single clod of earth which is truly their own” (Plutarch Tiberius Gracchus 9).

And this was the center of his program: doing something about the wealthy’s assault on the small-farm landowners who were disappearing as a class. But Gracchus was hardly looking to liquidate the rich: his proposal was to use a preexisting law that had been on the books for centuries that had long been unenforced, one which limited the amount of public land that any one individual could own. That limit was still quite large, but far less than what the ultra-wealthy had accumulated in the years of Rome’s great expansions, during which many Romans elites had used fake names to accumulate more than the legal limit. The excess land would be handed over to the poor, but in return for accepting this legal limit, all the legal-sized holdings would be formally recognized as legitimate and each son of these landowners would be given a portion of land equal to half the maximum size.

As would be expected, though, these wealthy landowners dominated the Senate, and they refused to go along with this compromise scheme even though the problems of ultra-concentration of land and wealth and the rapid rise of landless poor were all at a crises points.

Thus Gracchus, as was his legal-but-frowned-upon-and-untraditional right, called an assembly of the people and got his bill passed with the people’s enthusiastic approval. Equally as uncommon were for senatorial elites to orchestrate a veto of such a popular measure, but that the Senate did, co-opting one of the other nine Tribunes to veto Gracchus’ bill. Quite dramatically, Gracchus convened another assembly and had the people vote that tribune out of office: this dramatic move was extremely unprecedented, but was very likely still legal. The elites opposed to Gracchus were shocked at this move, and began a public relations campaign suggesting the Gracchus was out to make himself a king—just as offensive a suggestion to Roman sensibilities then as it would be to Americans today—and a portrayal Gracchus played into when he appointed himself and two of his relatives as the three-person commission to oversee the land reform. The Senate’s response to this was to refuse to allocate funding for Gracchus’s commission (if this sounds familiar to current U.S. politics on anything from Obamacare to the Zika virus, it should). In turn, Gracchus moved to get funding from future revenue from newly bestowed Pergamese lands in Asia, stepping into both financial and foreign affairs, policy spheres traditionally run by the Senate.

In pursuing his land reform and in its efforts to stop him at any cost, both Gracchus and the Senate were showing a willingness to discard centuries of compromise and precedent that had served Rome well, though Gracchus could at least in part be said to be acting on behalf of a Roman people and Republic in desperate need of land reform while the primary concern of the senatorial class was preserving their own power and obscene wealth.

Against such odds, Gracchus did something no Roman as a tribune had ever done before: he made it clear he would stand for election again to serve a consecutive second term as a tribune, signaling to the Senate that it could not just stall in the hopes of outlasting him or hope to simply overturn his legislation when he was gone. A group of Senators, in part feeling this was a major step towards Gracchus moving to make himself king, and obviously acting to preserve their own power and wealth, marched on an assembly of the people where Gracchus was present and beat him, and hundreds of his supporters, to death; afterwards, other supporters of his were executed, imprisoned, or exiled without trial.

*****

This was a terrible turn for Rome: for hundreds of years and not since the earliest days of the Republic had anything even remotely like this happened, and even then nothing remotely this bad: tribunes were as a matter of religion sacrosanct and inviolable; to try to harm one was considered a terrible sacrilege. Elites, even members of the Senate, had resorted to settling a political dispute with mass murder, killing a major elected office-holder. And from this point, Rome’s politics would be driven by two main parties: the optimates—self-dubbed “best-men” who were the conservative leaders of the aristocracy and the Senate and generally acted against reform or anything that would redice their wealth and power—and populares—bold men from within the aristocracy who were willing to challenge the optimates, drawing support from the people with populist programs aimed helping the masses—and the conflict between the two would eventually destroy republican government in Rome altogether.

In order to prevent mass unrest, however, the Senate let much of Gracchus’ land law stand, but this was a temporary measure and the Senate stopped the reform in 129, to the dismay of not only Roman citizens; at this point, much of Italy was not so much directly controlled by Rome as by other Italians whom Rome considered allies and were not legally full Roman citizens, and it was clear to all that these Italians were the junior partners in the relationship; these Italians had not been consulted on the ending of the reform, to their consternation. This provided an opportunity for the murdered Gracchus’ younger brother, Gaius, who, it seems, sought to gain their support when they were shut out of the decision-making process by the Senate, apparently by supporting a bid to make many of them full Roman citizens.

But when Gaius sought and won a tribunate for the year 123, this was only one of his many aims; he also ran for and won the tribunate for the next year, 122, without the cataclysmic reaction suffered by his brother for attempting the same thing.

If Tiberius could be thought of as something of a Bernie Sanders of ancient Rome, then Gaius was going to take more of a Hillary Clinton-like approach, trying to build a broad coalition designed to appeal to many swaths of society instead of a more narrow populist program and to make it harder for the optimates to brush him aside like they did his brother.

As such, Gaius Gracchus passed a law ensuring access to grain for bread to win over the urban poor; for the poor of the countryside, he suggested creating a new colony to settle people on the site where Carthage had once stood, in Africa; for an emerging middle-class of lower aristocrats and businessmen known as equites (who ran many of the publicani), he allowed them to bid for the lucrative tax-collecting contracts in the western parts of Pergamum’s former lands, now organized as the new Roman province of Asia (taxation was not undertaken directly by the government but was a task the Roman state contracted out to private companies); to this end, rather than have the bidding take place as would normally happen in the province itself (often abused by whichever Roman governor was there), Gracchus made sure it would take place in Rome, and instead of than splitting the taxation responsibilities for the province of Asia into multiple contracts, he made it a single contract for the whole province, an appeal to the support of the upper Roman business-class since only larger corporations could handle a contract on that scale (this move would have unintended blowback as it gave rise to the obscene growth in power of the publicani that would be such a huge problem for Romans decades later).

On the legal front, he ensured capital trials could only be conducted through a law or people’s assembly, preventing the Senate from conducting trials by decree, and any senator or official who tried to bypass this restriction was subject to prosecution. He also brought equites into juries, so that the dominant portion of the pool from which judges and jurors in most civil cases were drawn were now equites over senators by a two-to-one margin; additionally, one of his allies passed a bill that made equites total replacements for senators on the juries of extortion courts that tried provincial governors and other senatorial-level officials for corruption (senators had generally avoided convicting their peers), and a permanent extortion court was established.

But in casting such a wide net, Gracchus made himself vulnerable as well; his wily Senatorial opponents used his effort to help Rome’s Italian allies against him, convincing many Romans that extending citizenship to these people would weaken the power of Roman citizens themselves, and the senators also used their individual patron-client ties with many of the non-Roman Italian to keep a good number of them from supporting Gracchus. They also preempted his attempt to win over the rural poor by having two of their own put forth bills to establish colonies. His support apparently undercut, Gaius lost an election in which he ran for a newly-unprecedented third tribunate in a row, and a fight broke out between some of his supporters and those of one of the current consuls, a consul who had bitterly opposed Gracchus and was a personal enemy of his; the fight resulted in the death of one of the consul’s supporters.

The Senate’s response to this was swift and unprecedented: it passed an emergency decree against Gracchus, authorizing the consul to do anything whatsoever to take Gracchus down: Gracchus and thousands of his followers were killed in a brief yet bloody fight and subsequent executions.

From the Gracchi to Caesar: the Cycle of Political Violence Explodes Into Civil War

Sadly, violence would come with frightening ease and regularity over the following decades.

Close to four centuries had passed in Roman history without violent episodes other than some disturbances early in Rome’s history, but after the deaths of the Gracchi brothers in 133 and 121, violence increasingly became a political tool, beginning mainly with the Senate’s optimates’ efforts to squash would-be reformers challenging their power too much for their liking, first in 100 and again in 91, both used against tribunes and the latter being used on a man pushing for citizenship for Rome’s Italian allies; the assassination of their champion sparked a rebellion by many of Rome’s Italian allies called the Social War (91-88), which was only ended by Rome’s granting of most of them the citizenship they had wanted to achieve through peaceful means. But an actual civil war between roman military units fighting for supporters of one generally popularis consul (Gaius Marius) against the forces and supporters of another optimas consul (Lucious Cornelius Sulla)—Rome’s first civil war in over four centuries of republican government (consider it took the United States only 85 years before it had its Civil War from 1861-1865)—broke out the same year (along with a major overseas conflict in Greece and Asia). The period of conflict between supporters of Marius and Sulla would not finally end until 72 (and that foreign war not ending until 63).

But no rest for the weary: one ambitious popularis tried to overthrow the Republic after losing an election in 61, and he and his makeshift army were annihilated in 62. As the 50s unfolded, tension was constant and bouts of mob violence frequent, while the many pressing problems facing the Republic were left unaddressed by obstinate optimates who showed a total disregard for the Roman people. (Gaius) Julius Caesar would be their champion as a popularis, but his foes in the Senate would never forgive him; with a veteran army after his victorious war in Gaul, the Senate issued its emergency decree again in 49, basically authorizing tCaesar’s death because he would not step down from office; but this was after intense behind the scenes maneuvering in which Caesar’s supporters tried to negotiate a way for him to take up a new office when his term as consul expired, without which Cesar would be out of office and therefore open to legal prosecution, which his enemies were certainly planning for him. Essentially, they were daring Caesar to start a civil war or accept disgrace and prosecution and who-knows-what-punishment, in addition to an untenable political situation for the Republic and its citizens.

Caesar chose civil war.

By the time the wars which grew out of the civil war beginning in 49 ended nearly twenty years later in 30 with Caesar’s nephew Octavian defeating Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Rome’s people were so exhausted by war that they didn’t mind that Octavian set up a dictatorship masquerading as a republic, and thus the Roman emperorship was born. There would not be another large-scale democracy or democratic republic with as much participation by the people until the United States of America grew to be a major power roughly 1,800 years later.

America’s Own Problems With Political Violence: Civil War to Civil Rights

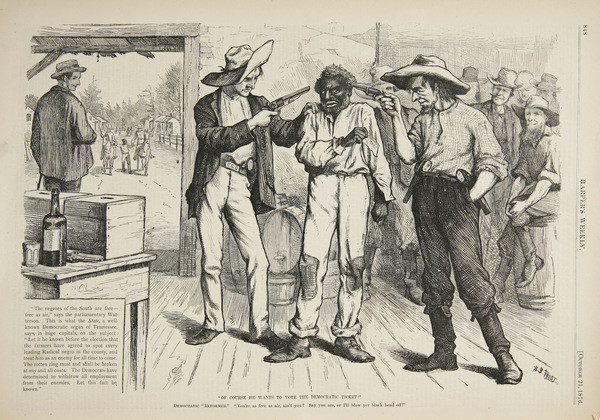

Harper’s Weekly- October 19th, 1872

That time would roughly coincide with America’s Civil War. The war itself did not really end in 1865: during Reconstruction, the Republican-dominated federal government with its army acting as an occupying force put into place new state governments in the Southern states that had rebelled that enforced racial political and legal equality for freed slaves, but over the course of the next decade and then some, Democratic extremist terrorist white supremacists carried out insurgencies and violently overthrew almost all these governments, putting in place racist governments highly oppressive and violent to black Americans that lasted until the 1960s; southern whites finally negotiated the withdrawal of federal troops left in the only remaining states southern white insurgents had not violently taken over after the disputed election of 1876, an election, like so many others between 1865-1876, marred in the South by widespread violence, fraud, and voter suppression.

Harper’s weekly- “Of Course He Wants to Vote the Democratic Ticket:” White Democrats intimidate a black Republican,October 21st, 1876

With the exception of the election of 1948, in which many southern whites punished Democratic incumbent Harry S. Truman for supporting civil rights for African-Americans and voted for racist third-party candidate Strom Thurmond, Democrats would continue to be the party of racists until John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson embraced equality for African-Americans in the 1960s, causing the parties to swap positions on issues of race, with white southern voters then defecting en masse to the Republican Party mainly because of racism, where they are now the Republican Party’s primary base. And, disturbingly, most of the states where today the state-level government is leading the charge in suppressing black and other minority voters are former “Confederate” states in the South.

America is fortunate that apart from riots and strikes, many of them race-based, there has been very few period of civil unrest since the 1870s, the main exceptions being the sporadic taming of the “Wild West” and later the Civil Rights Era’s 1960s and early 70s. But now, starting with the Ferguson riots in 2014 that was the first in a series episodes of racial unrest that have so far culminated in the dark days of racial tension of this very summer of 2016, we are seeing the most unrest this country has faced in more than 40 years.

Trump: The First Major Party Candidate to Stoke Unrest While Running for President?

And in the middle of all this is Donald Trump, the most polarizing major-party candidate since the election of 1860 that precipitated this country’s only civil war.

As history and even our own world today amply demonstrates, the sinister genie of political violence is prohibitively difficult to get back into its bottle once it has been unleashed; often, the attempt to rebottle it fails to succeed before the self-destruction of whatever state-structures were in existence, or before people turn to autocracy out of weariness of violence, with the violence itself often bred by a disintegrating public trust in major institutions. Most worrisome about Trump is that he is mixing subtle, implied threats of mass violence and/or intimidation with a very overt effort to obliterate trust in such institutions; just to recap, from the beginning of his candidacy and throughout, Trump falsely exaggerated how bad problems were with our institutions, even allowing for their increasingly problematic nature: first, he assailed the media and the party presidential nomination process as being “rigged” by elites to keep him down (that is, until he won and then stopped caring); added to this are his repeated allegations that the presidential voting system is rigged from top to bottom, with exhortations of his (largely white) supporters to be enthusiastic volunteer Election Day poll-watchers (in minority-heavy precincts), a task that only trained professionals are qualified to do (the parts in parentheses are understood even as candidate Trump does not emphasize them). Combined with his casual references to beating up dissenters at his rallies, his earlier threats/hints of possible violence (and his campaign’s preparations for intimidation tactics) were the Republican Party to try to deny Trump the nomination at its convention, his repeated musings as to what gun enthusiasts could show Hillary Clinton, especially if she were to be stripped of her Secret Service protection, and his stated desire to put Clinton in jail were he to be elected president along with his encouraging of chants of “lock her up” with crowds at his rallies, all Americans paying attention who have any sense of decency left should be feeling chills down their spines.

And yet for millions of Trump’s deplorable supporters, who are hanging on to every word in person at mass rallies, watching him on TV, or listening to him on the radio, they hear all this, easily understand all the implied subtleties about race and violence, and eagerly absorb every word joyfully, salivating at the very prospect of being able to assert their white dominance yet again on the political system, with far too many of these people also delighting in the prospect of political violence as a means to achieve these ends.

I wish I could say that I firmly believe such a prospect of political violence on anything other than a minute scale is a remote possibility, but I can’t; Trump’s recently far more sinister rhetorical turn is driving delusions and fantasies of violence in the heads of far, far too many of his flock, especially if that recent poll that had half of Republicans refusing to accept Clinton as president is even remotely accurate (and it probably is). I honestly don’t know what will happen, so extreme has Trump’s rhetoric become, so extreme have the views of many of his supporters been for some time, that I fear what will happen should this toxic mix boil over.

All Americans, regardless of political affiliation, in an atmosphere of increasing racial animosity and rumblings of political violence, should be afraid, and demand that Trump cease such rhetoric immediately, before it may be too late to prevent the unimaginable. But, as a consequence of all of this, we must begin to imagine the unimaginable, and prepare for the worst.

In some ways, that in itself is close enough to a 133 moment that we are in trouble regardless of what happens on and/or after Election Day.

Conclusion: A True Test for America, Its System, Its Leaders, Its People

I want to also be careful here to note I am not arguing inevitability here: 133 did not make Sulla’s and Caesar’s civil wars inevitable, and Trump doesn’t make anything inevitable about today’s America. But each made and make, respectively, the possibility of really bad things happening far more likely: once such things occur in a society, they are far more likely to occur again than if society had prevented them from occurring at all in the first place.

Do I think Trump really wants to spark violence and riots? To undermine democracy? Maybe not, maybe it’s just bravado, but maybe not; either way, I do not think he appreciates or understands the raw hatred and emotion with which he is toying; in fact, the Republican Party did not realize how dangerous a game they were playing for decades stoking these fires, and Trump blew it all up right in the Party’s elites’ face. These forces are larger than Trump, and it remains to be seen if he can contain them, or if he even wants to. At the final debate, he said he wanted to keep us “in suspense,” and no matter what happens, we can all agree he has succeeded wildly on that front, and not for the good of our republic. The example of Rome’s self-destructive descent into civil political violence and strife is frighteningly instructive for our times, then, and should give us all pause, and we will have to judge ourselves very much on the basis of what happens over the next few weeks. In some ways, no less than the fate of our (and even Western) democracy itself is at stake.

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here.

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter (you can follow him there at @bfry1981), and here are many more articles by Brian E. Frydenborg. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this content, or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!