A review of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World (by Catherine Nixey, Mariner Books, 2017 hc/2019 pb, 358 pages)

By Brian E. Frydenborg, December 26, 2021 (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981)

SILVER SPRING—As I write this on Christmas Day (and the day after), to any thoughtful Christians, on this particular occasion and as they read this particular piece, I will not wish them a “merry Christmas,” but forcefully implore that they think of certain others, if but for a moment (yet hopefully longer).

Much as some (hardly all and I doubt most) African-Americans and many (very probably most) Native Americans look at the Fourth of July—Independence Day—in America differently than others, let us spare some effort to consider the “pagans” of Late Antiquity, those who lived to see Christianity come to dominate the Roman Imperial government and those who came after to see their way of life virtually exterminated, save for some brave folks, mostly in the most rural of countrysides or remote mountains, farther from the reach of Imperial authorities.

Those “others” I ask to be considered are those who would have been the vast majority of the people living in the Roman Empire at the time from the era of Emperor Constantine’s rise to power in 312 C.E. (Common Era, an improvement, in my view, over the sectarian A.D.), in part due to his then-partial, not-yet-total, embrace of Christianity, and much of the population through the next few centuries as Christianity was forced upon the entirety of the Roman Empire—nearly every corner and nearly every person, certainly on anyone within clerical or Roman Imperial reach who was considered “pagan” (all non-Christian Romans who were not Jewish).

“Pagan” itself emerged as a Christian pejorative term, one the diverse range of polytheists and non-Jewish, non-Christian monotheists of the Greco-Roman world would never, ever have used to refer to themselves, as Catherine Nixey, author of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, is quick to point out in her brisk and energetic account of Christianity’s takeover of the Roman state, society, and culture. In fact, in the Roman era before Christianity’s takeover of Rome, it was not at all common for people to define themselves primarily or in large part by their religion (Jews, of course, were a tiny exception during this period); the sharp delineation of people as being of one religion or another as a core part of or primary indicator of their identity was, in any widespread sense, an invention of the Christians of this era (and a rather regrettable one). If you were a good citizen and obeyed the laws of Rome, before, Romans generally didn’t give a fig what gods you or anyone else worshipped. You were free to ignore their gods just as much as you were free to adopt them or worship your own, and there was not a feeling that by believing in your gods that that meant you had to deny anyone else’s gods, let alone call them demons. Apart from the sensitive situation with Jews and Judaism, this is essentially unheard in this time outside Christianity.

But Nixey’s point is that it is essentially unheard of today because triumphalist Christian accounts have shaped our view of this distant era into, primarily, the following:

After centuries of fierce persecution at the hands of sadistic pagan Romans, Christians inevitably rose to dominate the Roman Imperial sate, destroy the false gods (actually demons serving the Devil) and old religions (cults celebrating evil and Satan) that had dominated the Roman world but never really captured the hearts and minds of the people, free the people from evil and superstitious idolatry by benevolently bring the light of the One True Faith and One True God to them, and led mankind into a new era of truth, love, and kindness based on God’s Law and God’s Love. And, all through the ages, the Church preserved the wisdom of the ancients by painstakingly copying their texts in monasteries that became centers of learning, scholarship, and wisdom.

The truth could not be further from this false account (apart from monasteries preserving some classical texts after Christians had destroyed nearly all the others), and Nixey is here to correct the record.

She quickly and skillfully dismisses any accounts of being biased for not focusing on the examples of kindness, compassion, and scholarship that Christianity has given to the world, as that story has been told by the Christian victors time and time again, ad nauseam and often greatly embellished, exaggerate, or omitting key context. No need to tread well-trodden and built-up, tended ground; no, in her book, it is the suppressed, even obliterated, the voiceless and long forgotten, whose mantle she takes up to give voice to and whose feelings, thoughts, and very existence she is determined to present to us.

And she presents it well. This is not a book of deep scholarship nor one that will meticulously trace the Christian revolution and the genocide (certainly by our modern legal definition) of “pagans” in its entirety, throughout the whole of the Empire, event by event, discussing the scholarly debates in detail about this and that motive or event. Instead, she is keen to connect emotionally with her readers, recreating with literary dash what it might have been like to think, feel, and experience the times, places, events, and people about which she is writing, especially those perspectives long lost, suppressed, or ignored. To this end, she selects a smattering of major events and narratives throughout the several centuries in question and throughout the empire, giving context and descriptive recreations for each, peppered with quotes from Christian and “pagan” alike.

And the picture she paints should give Christians and anyone not familiar with the truth pause, much in the way Americans who are not Native Americans might pause when thinking about Thanksgiving or Manifest Destiny, or, indeed, the very land on which they live. This is because the ground on which Christians rose to control the Roman Empire and Western World was laid with a foundation of ash, rubble, and blood from the destruction of the existing world—ash, rubble, and blood that came from Christian violence, destruction, or murder of “pagan” books, temples, and worshippers.

A Record of Pious Sacrilege

Much like the later Crusaders, Nazis, Stalinists, Maoists, and ISIS, none of this is in doubt because these Christians gleefully recorded many of their atrocities and killings, immortalizing them in hymns, arts, and the texts of the early Church Fathers (indeed, they often sang joyously as they went about their destruction and murder). Figures like Augustine and (even more so) John Chrysostom openly sermonized to their congregations to commit violence and murder against not just pagans who would not get with the program but any wayward or erring Christians, for doing so was not a net harm: it was out of love, since it was deemed better to harm the body in this life than to allow the soul to writhe in eternal hellfire in the next. In the words of Augustine, “where there is terror, there is salvation… Oh, merciful savagery!” (240). For Chrysostom, if a Christian heard a person blaspheme against the Christian god or Christian teachings, “go up to him and rebuke him; and should it be necessary to inflict blows, spare not to do so. Smite him on the face; strike his mouth; sanctify thy hand with the blow” (234-235). Similar sentiments would be proclaimed by many other bishops, priests, and monks. For one eventual saint, the ends justified any means: “There is no crime for those who have Christ” (230). It was clear that if any Christian zealotry broke Roman law or violated the legal rights of the target of their righteousness, such concerns were illegitimate when placed next to the laws of God. In fact, if Christians were killed while attacking “pagan” temples, clergy, or worshippers, such “martyrs” would be richly rewarded in heaven and forever exalted among the faithful on earth. Sound familiar? It is Christian jihad in the ISIS sense. And many of the men committing these crimes are saints even today in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, or both (even other Christian sects, too).

How did this revolution take hold? In the smashing of temples and statues to rubble, the mass burning of books and the barging into people’s homes if they were merely suspected of having “pagan” art or literature, a hating of sex and sexuality, theatre, music, dance, and festivals, all of which were seen as the work of demons and punishable by violence and torture. Shaving, for many, was a sign of “pagan” inclinations (even, too, any kind of colorful fashion, showing of skin for women, or taking especial care with bathing and hygiene). Science, math, objective history, philosophy were also “pagan” demonic works since they did not neatly line up with Christian teachings, and scientists, surgeons, teachers all saw works of theirs purged and burned, their places of operation shuttered or destroyed if they did not adopt Christian ways (and for many of them, this would have made their work impossible or compromised their values and beliefs to a level beyond that which they could bear). The stubborn or those who spoke out against these restrictions were forbidden from continuing their trade, tortured, exiled, or murdered, their property seized and their works obliterated from the face of the earth. The intellectual and the worldly is despised. Misogyny is pervasive. Homosexuals were newly tortured, their genitals often cut off, often leading to death.

This, too, was an era of thought crimes, and absolute destruction of free speech, inquiry, and debate enforced by murder and torture, often with the full backing of the state but also often by mobs of incited and dispatched-by-a-cleric Christian lay folk for whom there was little to no accountability. In her account of the terrible murder—just for having respect and influence as a non-Christian and a woman—of Hypatia, a female philosopher based in Alexandria and renowned throughout the Empire in her day for her brilliance and wisdom, sought after by local rulers and the sons of elites from across the Mediterranean—Nixey notes that her close confidante, the local Roman in charge named Orestes, is helpless with his small retinue to stand up to the hundreds of militarized Christians known as parabalani—“the reckless ones,” a sort of YMCA cohort but with a distinctly terrorist bent (135)—who enforce the will of their extremist bishop (Hypatia and Orestes’s tale is wondrously depicted in Alejandro Amenábar’s 2009 film Agora, the two characters poignantly portrayed by Rachel Weisz and Oscar Isaac).

Terrifying Modern Parallels and Digging into an Ancient Mentality of Hate

Reading these accounts, one cannot but help see the giant overlaps with ISIS; indeed, these Christians come off as the ISIS of Christianity, Rome under their rule resembling Baghdadi’s caliphate or Afghanistan under the 1990s Taliban (not today’s apparently—for now at least—relatively kinder, gentler version). Even today, Christianity celebrates these terrorists and murderers from its infancy. The harshness of their rule; their hatred of free inquiry, joy, merriment, and women’s autonomy; their self-adoption of the roles of judges, jury, and executioners; even their appearance—both ISIS and the early Christian enforcers were generally severe young men in dark clothing with unshaved beards—bear such a distinct resemblance to the worst of ISIS and Taliban rule, the worst of the terrorists of our own era, that it is hard to see the difference between them as you read Nixey, hard to not see them as one in the same, with the most extreme of religious terrorists in our modern era clear inheritors of a clear tradition that more or less begins with these Christian fanatics (“saints”).

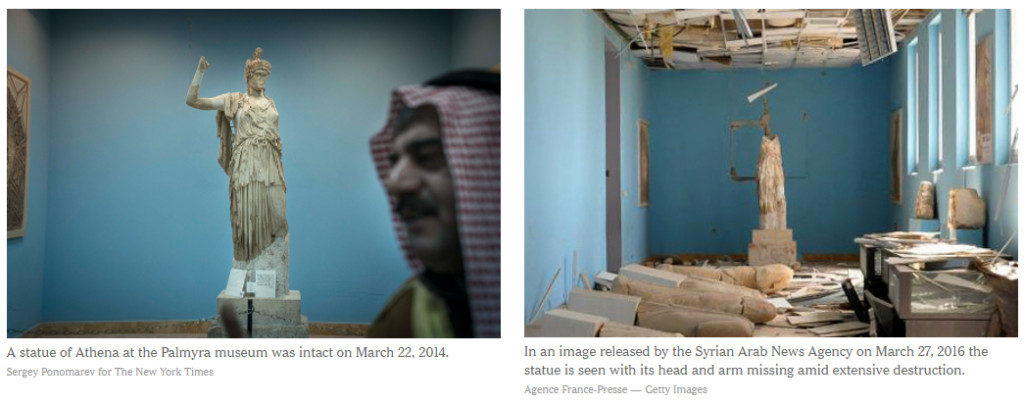

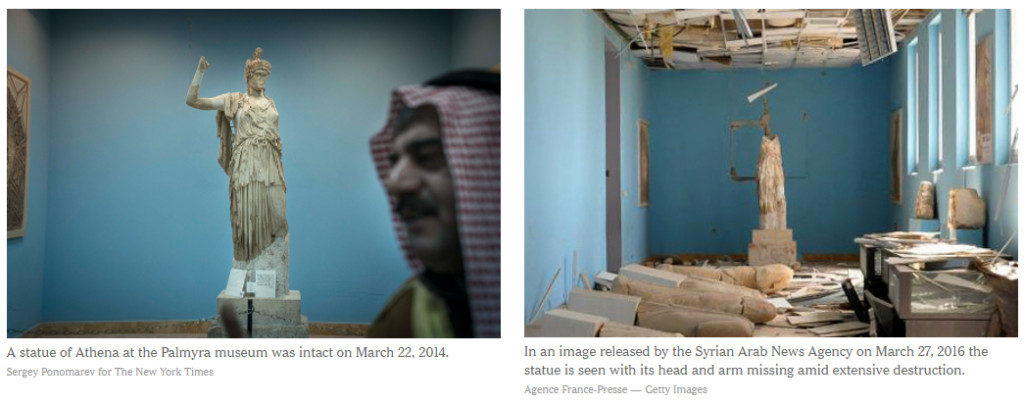

If you doubt this, consider that, after a statue of Athena in Palmyra at the ends of the Syrian desert was desecrated and mutilated by Christians in the 380s, the very same statue, partially restored and on display in the second decade of the twenty-first century, was similarly desecrated and mutilated when ISIS took over the city in 2015 (xxxi, 114). Just like their Christian and Jewish religious forebears, they were simply carrying out God’s explicit, clear command to destroy “idols,” as had the Taliban in 2001 with two massive Buddhist statues.

But to truly understand the mentality of these hostile faithful from Rome’s era of religious tumult, we need look to nothing other than the Ten Commandments. Depending on your religious sect or faith, the following either comprises the first two or first three of the Ten Commandments:

I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.

You shall not have other gods beside me.

You shall not make for yourself an idol or a likeness of anything in the heavens above or on the earth below or in the waters beneath the earth;

you shall not bow down before them or serve them. For I, the LORD, your God, am a jealous God, inflicting punishment for their ancestors’ wickedness on the children of those who hate me, down to the third and fourth generation;

but showing love down to the thousandth generation of those who love me and keep my commandments.

You shall not invoke the name of the LORD, your God, in vain. For the LORD will not leave unpunished anyone who invokes his name in vain. —Ex: 20:2-7

Badmouthing or criticizing God? The same punishment:

A man born of an Israelite mother and an Egyptian father went out among the Israelites, and in the camp a fight broke out between the son of the Israelite woman and an Israelite man.

The son of the Israelite woman uttered the LORD’s name in a curse and blasphemed. So he was brought to Moses—now his mother’s name was Shelomith, daughter of Dibri, of the tribe of Dan—

and he was kept in custody till a decision from the LORD should settle the case for them.

The LORD then said to Moses:

Take the blasphemer outside the camp, and when all who heard him have laid their hands* on his head, let the whole community stone him.

Tell the Israelites: Anyone who blasphemes God shall bear the penalty;

whoever utters the name of the LORD in a curse shall be put to death. The whole community shall stone that person; alien and native-born alike must be put to death for uttering the LORD’s name in a curse…

You shall have but one rule, for alien and native-born alike. I, the LORD, am your God.

When Moses told this to the Israelites, they took the blasphemer outside the camp and stoned him; they did just as the LORD commanded Moses. —Lev. 24:10-16, 22-23

You read Leviticus and Chrysostom correctly: the punishment applies even to those who aren’t Christian.

As an adult, I am struck by how these first commandments (including the Third or Fourth, depending, again, on the faith/sect, to keep the Sabbath holy)—three out of ten or four out of ten, no small portion—have absolutely nothing to do with morality, with right or wrong, but are about a jealous—even petty—God who will brook no competition or criticism, and, indeed, has ample punishments and miseries in store for those worshipping other gods or criticizing him in both Jewish and Christian (and Muslim) scripture (perhaps there is room for much improvement?). Pagan idolaters are to be killed, their shrines and statues destroyed, murder and destruction ordered directly by God himself. Just one example here:

If your brother, your father’s child or your mother’s child, your son or daughter, your beloved spouse, or your intimate friend entices you secretly, saying, “Come, let us serve other gods,” whom you and your ancestors have not known,

any of the gods of the surrounding peoples, near to you or far away, from one end of the earth to the other:

do not yield or listen to any such person; show no pity or compassion and do not shield such a one,

but kill that person. Your hand shall be the first raised to put such a one to death; the hand of all the people shall follow.

You shall stone that person to death, for seeking to lead you astray from the LORD, your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.

And all Israel shall hear of it and fear, and never again do such evil as this in your midst.

If you hear it said concerning one of the cities which the LORD, your God, gives you to dwell in,

that certain scoundrels have sprung up in your midst and have led astray the inhabitants of their city, saying, “Come, let us serve other gods,” whom you have not known,

you must inquire carefully into the matter and investigate it thoroughly. If you find that it is true and an established fact that this abomination has been committed in your midst,

you shall put the inhabitants of that city to the sword, placing the city and all that is in it, even its livestock, under the ban.

Having heaped up all its spoils in the middle of its square, you shall burn the city with all its spoils as a whole burnt offering to the LORD, your God. Let it be a heap of ruins forever, never to be rebuilt. —Deut. 13:7-17

As a child growing up in America, these first few of the Ten Commandments always struck me as odd: everyone where I was (and, indeed, virtually all of America in the 1980s) was either Christian or Jewish, worshipping the same God if differently. But back when Constantine began to favor Christianity in the early fourth century C.E., Christians were a small minority, surrounded generally not by other monotheists (the most notable exception being Jews concentrated in a few areas, though a considerable number of “pagans” practiced different monotheisms) but by polytheist worshippers of Greco-Roman gods or their Celtic, Germanic, North African, Egyptian, or Eastern equivalents. The presence of competing “false” gods—Paul clearly states they are not just false, but actual evil demons—would have been overwhelming to a Christian.

So while we today shrug at passages about idols and pagans, in the context of early Christianity, nothing was more important than placing the Jesus/God before the myriad of other gods and God’s words were clear in this most important, most emphasized of Christian teachings: idolators and competing gods were not to be tolerated but utterly destroyed, their worshippers forced into submission and conversion or killed. Thus, the most important part of being a good Christian was not loving your neighbor with kindness, but accepting the One True God in a way that demanded non-acceptance, confrontation, and violence with neighbors if they did not accept Christianity.

We must go back in time to realize that, in daily life, it was almost impossible to escape the presence of these “demons”: giant, exquisite statues regularly lavished with public sacrifice and worship in the most prominent places of any village, town, or city. For early Christians, they were living in a time of never-ending holy war, an age of terror in which, as laid out by scripture and endlessly repeated by Christian clergy, the evil demonic gods that surrounded them wished them harm, sought to steal and condemn their souls through temptation, and were challenging their own God for supremacy.

In this mindset, every painting in a bathhouse or a private home with naked people, every bit of incense, every statue, every book of “pagan” filth, was part of this never-ending campaign against Christianity and must be destroyed. Even if the masses were not zealous enough, over the centuries after traditional Greco-Roman religion and philosophy were nearly wiped out, the stones of the remnants of the last “pagan” temples and marble of the remaining “pagan” statues would be broken up to build churches or repair houses or other infrastructure; Plato or Cicero would be erased and replaced or written over with Paul or the texts of the early Church Fathers. So, to a large extent, these people and their culture were destroyed, often utterly. That is why so few works of the art and literature from this era remains–less than ten percent of classical literature survives today, including only one percent of Latin literature [177])—that is why nearly every statue from the period shows hacked-off noses, gouged-out eyes, chipped-away nipples, or some other deliberate mutilation.

I am always amused when people claim Christianity (or Judaism, or Islam, the latter’s texts and traditions containing similar injunctions, even with the behavior of Prophet Muhammad himself) is a religion of peace. Christians will often say that “Jesus came to change the ‘bad’ stuff in the Old Testament (Jewish Torah), making Christianity all about love,” having obviously not studied their New Testament well at all, where Jesus clearly and repeatedly affirms the Old Testament laws (and while there are some New Testament examples apparently changing some Old Testament rules, they are not as forceful, clear, or as far-reaching). And let us not forget that all those who do not accept Jesus as their God, Lord, and Savior are doomed for an eternity of fire and torture in Hell. It is not a “misreading” or “taking out of context,” as these verses in favor of preserving the laws of the Old Testament are not parables, but crystal-clear affirmations. After all, Christianity bases its entire legitimacy on fulfilling the prophecies of Jewish scripture and on the God of the Jews.

The Buried Ugly Truth of Early Christianity and Its Lessons for Today

It was the Christians who persecuted en masse, not the other way around; despite the popular image of Roman persecutions of Christians and feeding helpless mothers and children to the lions in the Colosseum, Nixey takes pains to point out that Roman persecutions of Christians were mostly few and far between, half-hearted and not widespread or intense, as low as “hundreds, not thousands” in their total victims, certainly far fewer than tradition has made it seem. If Romans had really wanted to wipe out Christianity, it would not have been hard: the Bible would have been incredibly difficult and time-consuming to produce in those days, and a concerted effort to burn all the Bibles and silence the clergy would almost certainly have succeeded (indeed, later Christians would succeed in wiping out numerous other cults), and such success would have been an enormous obstacle for a religion based on the Word of God.

Yet for Christians then and too many of them now, like ISIS or even Trump’s Capitol insurrectionists, it is they themselves who feel they are and must be the victims and it is their victimhood that justifies their own extremism violent atrocities against innocents. Whether it is Christian terrorists in America or Muslim or Jewish ones in the Middle East, the culture of victimhood elevates them and their narratives, to the exclusion of those they target. In the end, the mentality of those who feel they must kill and destroy to preserve God’s will (really their own interests) reveals a pitifully weak “God” and a resentful, inferiority-complex-ridden class of warriors, traits consistent from the fourth century into the twenty-first.

It is for us, then, to remember these truths, even on a day like Christmas. As perfectly articulated by the late and singular Christopher Hitchens:

Many religions now come before us with ingratiating smirks and outspread hands, like an unctuous merchant in a bazaar. They offer consolation and solidarity and uplift, competing as they do in a marketplace. But we have a right to remember how barbarically they behaved when they were strong and were making an offer that people could not refuse.

Let us close on that note, remembering how many Roman “pagans” were made offers they could not refuse. While it is undoubtedly true many people did convert to Christianity willingly and with a true heart, many others converted “willingly” from a threat of loss of status or their livelihood; many others from threat of torture, murder, or execution. Many were tortured and executed, many did lose their jobs. Many, under such conditions, would succumb and convert outwardly, if not in their hearts; many others who loved their children would have raised them as Christians so as to spare them constant harassment and violent threats. Some would have simply done publicly the bare minimum to avoid legal trouble, others publicly genuinely worship Jesus as another god and privately still worship their own gods.

Still, so it is that in a few generations, most Romans were “Christians” in a place where being a pagan had literally become a death sentence. Under such conditions, it is doubtful a majority of converts over time were genuine or truly willing, but many of their lives were snuffed out, their voices obliterated to history. As John Chrysostom joyfully noted in somewhat exaggerated fashion in one sermon, the written works “of the Greeks have all perished and are obliterated;” in another, “Where is Plato? Nowhere! Where Paul? In the mouths of all!”

More than we would have thought in remote parts of the now officially Christian Roman Empire, some “pagans” would have persisted in their traditional beliefs, quietly and illiterately. But their world was dying out, their heyday long gone, they were the exception, not the norm, and they leave virtually no record. The few words from “pagans” in their twilight are wholly depressing, often learned scholars living to see their teachings banned, their books burned, ignorance and credulity reign, knowing they are part of a world where the inmates have taken over the asylum. For one Palladas, it is a time he and his kind were “men reduced to ashes… for today everything is turned upside down,” and he asks:

Is it not true that we are dead and only seem to live, we [who worship the old gods]… Or are we alive and is life dead? (xxvi).

At least in Nixey’s if not Christianity’s account, they live on and their voices are heard and remembered.

Whatever the properly understood teachings of Christianity or any religion, let us hope that all faiths and faith leaders can one day insist on changing these rules to allow for complete tolerance and non-violence towards all other faiths and people of no faith such that no people today suffer the treatment of Nixey’s “pagans;” for even in recent years, Yazidis have suffered like this under ISIS, such that one Yazidi survivor turned Nobel laureate, Nadia Murad, wrote a memoir called The Last Girl, as in she hopes she is one of the last girls to go through such an attempted religious genocide. In the same vein as Paul and the early Christians, ISIS saw Murad’s Yazidis as “pagans” and therefore Devil-worshippers; Christians of the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries would have been proud of ISIS for assaulting the “pagan” Yazidis (indeed, Islam has borrowed much from Christianity it would have been better off not).

Perhaps Nixey’s narrative can remind us no faith or people is exempt from the possibility of such horrid conduct meted either by or against them, and can add to the possibility that Murad’s earnest, deeply necessary plea is heard.

© 2021 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!