The nature of warfare is changing and cyberwarfare is increasingly the battlefield on which our battles against our enemies are and will be fought, as Russia’s recent unprecedented SolarWinds hacking operation and other recent attacks make even clearer. Russia is embracing this future while NATO struggles to respond. The Alliance’s core founding treaty must reflect this new reality or NATO will suffer.

A Real Context News Special Report also available as a PDF file

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981) June 7, 2021; updated June 15, 2021, to take into account the June 14 NATO summit in Brussels; cited by NATO LibGuide on Cyber Defence; condensed rewrite for Small Wars Journal September 24 also cited by NATO LibGuide on Cyber Defence and featured by Real Clear Defense; see Brian’s related review of one of the most important books on national security to come out in years, Nicole Perlroth’s groundbreaking This is How They Tell Me the World Ends; see his related articles: December 24, 2020, The History of Russia’s Cyberwarfare Against NATO Shows It Is Time to Add to NATO’s Article 5; February 17, 2017, Trump, the Global Democratic Fascist Movement, Putin’s War on the West, and a Choice for Liberals: Welcome to the Era of Rising Democratic Fascism Part II; and December 7, 2016, The (First) Russo-American Cyberwar: How Obama Lost & Putin Won, Ensuring a Trump Victory

SILVER SPRING—Alliances between nations must adapt to retain power over time, and in no area has warfare evolved more in recent years than in cyberwarfare. Article 5 of NATO’s founding 1949 North Atlantic Treaty mandates that if an “armed attack” is carried out against a member state, all member states (currently thirty, including the most powerful Western nations) “shall” consider that attack and any armed attack on even just one member state “an attack against them all” and “will assist” it, up to and “including the use of armed force.” As the centerpiece for over seventy years of the West’sPax Americana, global military power, system of alliances and collective defense, and ability to project combined strength anywhere on the planet, NATO must adapt to the present by adding cyberwarfare—including information warfare—to Article 5.

Cyberwarfare As Modern Warfare

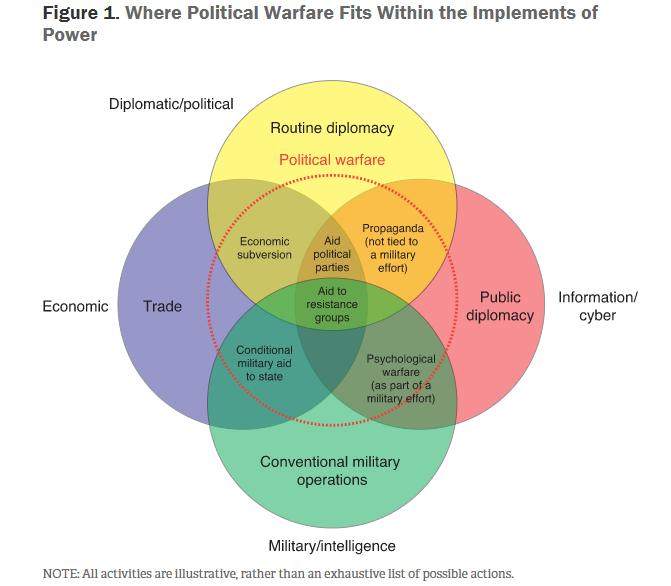

An obvious point in favor of including cyberwarfare in Article 5 is that, by far, the most effective, damaging, and destabilizing attacks against NATO countries since 9/11 have been cyberattacks, most carried out by Russia. The term “information warfare” (“a new face of war,” quoting a RAND Corporation report) refers to a key element of this cyberwarfare and includes the word warfare to indicate these are hardly benign, normal influence operations and are, indeed, the types of operations that have always been part of any serious conventional war in modern times. Even in the nineteenth-century, von Clausewitz wrote that “War is…an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.”

The ever-evolving concept of warfare in our digital age, then, does not have to include shots being fired from guns, and it is naïve to not consider cyberwarfare as simply another form of war in the twenty-first century that uses force in the digital realm to achieve results in some of the same spirit as traditional armies: attack, defense, deception, sabotage, destruction, and to pressure actors to change behavior. Clausewitz most famously wrote that “war is merely the continuation of policy [or politics] by other means” and would have well understood cyberwarfare (sometimes just termed cyberwar) to be war and well within that “other means” category.

The two countries that have led in cyberwarfare are Russia and China, the first (and weaker, but bolder) being NATO’s (and America’s) clearest top state enemy (even if unofficially but clearly in a de facto sense), the second (and stronger, more reserved) being America’s clearest top state rival in a holistic sense, as China has engaged and led in much non-weaponized hacking and espionage (admittedly common among major powers), but has not, say, brazenly released stolen information or disinformation in a way timed to significantly interfere with NATO member states’ elections (as Russia has). And though China has its own sophisticated influence operations, Russia undisputedly has led by far in acts more hostile than espionage (uniquely so among major powers) since its watershed 2007 Estonia cybercampaign (such campaigns might better be termed cyberassaults than cyberattacks, the latter a broader, far more common term which can even apply to a single high school student’s cyberattacks against his own school district).

Russia officially views NATO as a “threat,” and since that 2007 Estonia cybercampaign, has become far more aggressive and threatening towards NATO, often playing with internal NATO nationalisms and blanketing NATO nations in cyberattacks, including election interference and bolstering of secessionist campaigns, with notable cybercampaigns being carried out against over twenty NATO member states (leaving aside its campaigns waged against non-NATO states).

Furthermore, de facto, non-declared wars are the most common type of war in the modern era even if the term “war” is not specifically used. America, for example, has a long history of undeclared war going all the way back to the Articles of Confederation and the early days of the Washington Administration involving conflict with Native Americans and also the John Adams Administration’s 1798-1800 Quasi-War, then popularly termed “The Undeclared War with France.” Furthermore, as one scholar notes, “the legal state of war is possible without actual fighting.”

Taking all this into account, then, it is hardly unreasonable to consider Russia and NATO in a state of undeclared cyberwarfare and, therefore, a state of undeclared war. One of NATO’s flagship publications, NATO Review, even published analysis in 2017 acknowledging that Russia was waging “non-kinetic political war on the West.”

In fact, as I have argued for some time, a truly deep look would expose Putin and his Kremlin conducting a clear de facto war to destroy NATO, the West, the EU, and Western democracy; to fracture trans-Atlantic and European unity and even the unity of individual Western nations; and to foment, fund, and favor the rise of far-right ethno-nationalists and secessionists friendly to Russia and hostile to the U.S. and NATO in NATO countries and elsewhere, all while savaging those in the center and mainstream left not preferred by Putin. The parties Putin helps usually have much in common with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s banally nationalist United Russia party, which has struck up mixes of formal and informal alliances with several significant European political parties in major NATO states.

Though there have been military moves by Russia in Ukraine and Georgia—two NATO aspirants—the main weapons in its undeclared war on NATO are not tanks, bombs, or jets; rather, they are bots, trolls, and fake news.

The Nature of Russian Cyberwarfare Confronting NATO

Through hacking, disinformation, propaganda, and other cyber-methods, Russian campaigns that advance this war have been able to affect political outcomes in numerous NATO countries to suit (or, at least, more suit) Putin’s agenda. These efforts are coordinated through powerful branches of the Russian government and close Putin allies in and out of the Kremlin, often using thousands of fake accounts to artificially bolster the reach of their lies, which, in turn, are augmented within the target countries by native agents and allies (with unwitting true believers long being dubbed “useful idiots”). In many NATO countries—including the U.S.—Putin is even popular with far-rightists, no doubt in part because of Russia’s robust information cyberwarfare.

Reigning as the supreme disruptor on social media, Russia spews a “firehose of falsehoods” that has been massively effective, distorting and gaslighting the public discourse so that Russia’s preferred narratives are wildly amplified beyond their natural organic reaches, influencing many millions, thus helping to create an atmosphere where disinformation is sometimes consumed even more than actual news and doubt about even basic truths becomes widespread.

Domestic media outlets can be crucial instruments to this end of Russia’s, not only enthusiastic right-wing media outlets, but also far-left media outlets and figures (Glenn Greenwald and Matt Taibbi being two of the most prominent examples); as long as the Russian narratives further their narratives—usually attacking more mainstream and/or moderate parties and figures—these more extreme domestic outlets are often happy to unquestioningly parrot the Russian-projected “information,” and whether it is illegally hacked or not even vetted matters little to them. The distortions, lies, and unsubstantiated claims then become such a large part of the conversation that mainstream media latches onto this disinformation—sometimes echoing it, other times critiquing it yet still amplifying it—and the Russian narrative itself then becomes mainstream, as I have previously explained in detail.

And once Putin’s favorites are in office in part because of Russian disinformation, they in turn further spout Russian disinformation from the highest levels of the government and even copy Russian tactics (as former FBI counterintelligence agent Asha Rangappa illustrates with the U.S. case). They also pursue policies favorable to the Kremlin (e.g., weakening anti-Russian sanctions or creating geopolitical power vacuums for Russia to fill) and obstruct investigations into Russia’s cybercampaigns, making it all but impossible to effectively fight back. Terrifyingly, both America’s 2019 Mueller report and the British Parliament’s Intelligence & Security Committee’s exceptional Russia report released last year note damning examples of obstruction in their respective governments.

With such additional feedback loops, Russian cyberwarfare is thus a gift that keeps on giving, with domestic news outlets and coopted politicians doing Russia’s dirty work for and alongside it.

The Big One: Targeting America

The revelations of Russia’s devastatingly far-reaching months-long government and corporate espionage hacking, known as the SolarWinds attack, and the Russian cyberattack against the third-party-run e-mail system of America’s main international aid agency, USAID (a multipronged attack that used access to that system to hit some 150 government agencies, think tanks, non-profits, and human rights groups that have been critical of Putin and Russia)—both carried out by the S.V.R., Russia’s equivalent of the C.I.A. and one of the main successor agencies of the notorious Soviet K.G.B.—highlight recently exposed Russian cyberwarfare against the U.S., NATO’s largest pillar.

The same can be said for a recent significant attack on major U.S. cybersecurity firm FireEye, almost certainly also carried out by the Russian government, and for two recent ransomware attacks—one on the Colonial Pipeline and one on meat plants of JBS, the largest fuel pipeline and meat producer in America, respectively (in the latter, plants in Canada and Australia were also hit). These ransomware cyberattacks were carried out by DarkSide and REvil, respectively, two criminal hacking groups thought to be based in Russia or former Soviet-dominated states and that are widely understood to have tacit approval and protection from the Kremlin (to put some perspective in an aside here, it should be noted that after al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks—the only time NATO ever invoked Article 5—Afghanistan’s Taliban regime was overthrown by the U.S. because it gave harbor to al-Qaeda and did not hold the terrorist group to account, refusing to comply with American demands to shut down its camps, hand over its leaders, and arrest the rest of its members).

Much like Russia farms out parts of its aggressive foreign policy to Russian oligarchs, the Russian mafia, and Russian mercenaries in playing a sordid, cynical game of “deniability,” (something I have noted many times before), so too does it work similarly with hackers outside the Russian government.

Prior to the recent discovery of the activities outlined above, Russian cyberwarfare efforts against the U.S. have included clearly and repeatedly promoting unrest and division, pushing both disinformation about the coronavirus and illegitimate conspiracy theories of coordinated massive fraud in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Before the election, the Russians’ cyberwarfare effort was all-in on attacking the main political rival (Joe Biden) of their preferred top candidate (Donald Trump).

Of course, division and brainwashing in America have hardly been created by Russia, but it is and has been obvious that these efforts are hardly in vain: multiple credible surveys and any casual examination of social media show that vast swaths of the American public—even many in senior leadership—are buying into this disinformation, believing nonsense about both coronavirus (including millions doubting coronavirus vaccines) and the 2020 presidential election. All this undermines effective public health measures (literally helping kill Americans) and confidence in the very foundations of our electoral democracy. In addition, all this Russian content and its fallout obviously does not stay confined to America: international populations’ opinions of America and its political system along with their own views on coronavirus and vaccines are being affected, too.

In the words of journalist George Packer, “antisocial media has us all in its grip.”

The new Biden Administration, then, has its greatest initial challenge—the coronavirus—made even worse by this Russian cyberwarfare even while it will face an unprecedented (excepting Lincoln) crisis of legitimacy in the eyes of millions of misinformed (and disinformed) Americans.

Cyberwarfare a Larger Threat Now to NATO than Terrorism

Russian cyberwarfare focused on election interference in the U.S. in 2016—what I called back in December of that year the First Russo-American Cyberwar—has already caused damage to America, its democracy, and its reputation that is hard to exaggerate, with effects not only still being felt by the U.S. but guaranteed to still be felt for some time. In contrast, physical terrorist attacks in NATO countries since 9/11, while tragic, have still had comparatively limited effects. Even Russia’s own 2018 Novichok chemical weapon attack on British soil against Russian military intelligence officer turned spy for the UK Sergei Skripal in Salisbury had more symbolic an effect than anything else, dwarfed by the damage from Russian efforts to tip the 2016 Brexit vote in the direction of Leave or the effect of Russia’s campaign to amplify Scottish secessionism (now increasingly likely and sooner rather than later, an outcome that would obviously fracture and devastate a UK already severely weakened by Brexit).

As I explained in my analysis of the aforementioned excellent British parliamentary committee report on Russia, Britain’s own official self-reflection made it clear that the solid response (and solid effort to bring in allies to take part in this response) to the Salisbury attack needs to be replicated when it comes to other Russian hostile actions, the clear implication being to include Russia’s cyberwarfare, especially political interference.

The same idea can be applied to NATO as a whole, which does have a Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence located in Tallinn, Estonia. Yet even today, one-sixth of NATO—Canada, Luxembourg, Albania, Iceland, and North Macedonia—are not members of this Centre, though, encouragingly, the first two are in the process of joining, new members have recently been added, and non-NATO states Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland are “Contributing Participants,” a status available to those outside of NATO; other non-NATO states Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Ireland also intending to join in that capacity. There are also plans for a new military cyberdefense command center to be fully operational in 2023 at the main NATO military base in Belgium.

Overall, NATO considers “cyber defence…part of NATO’s core task of collective defence” and has since 2014, when the Alliance first explicitly laid out the theoretical possibility of invoking Article 5 in response to a cyberattack (though only “on a case-by-case basis”). Since then, NATO has “pledge[d] to ensure the Alliance keeps pace with the fast evolving cyber threat landscape and that our nations will be capable of defending themselves in cyberspace as in the air, on land and at sea,” repeatedly reiterating the possibility of Article 5 being invoked in response to a cyberattack, including just this past September.

Update June 15: A communique issued by NATO from its Brussels summit on June 14, 2021, is heralded by some, including the White House, as a “new” cyberdefense policy but actually reiterates already vague and repeatedly articulated positions discussed above, namely, that NATO states “reaffirm that a decision as to when a cyber attack would lead to the invocation of Article 5 would be taken by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis,” hence, nothing much really new in actual policy and note the use of “reaffirm.”

Falling Short

Official working papers, conferences, interviews, statements, and raising possibilities on the subject are one thing, but a concrete, clear policy is another, and NATO has nothing of the sort.

The vague idea seems to be that if a cyberattack was “serious” enough, Article 5 would be invoked, but there is no definition of what this threshold would be, and, frankly, this idea seems rather myopic: death by a thousand cuts is still death and has the same effect as decapitation, so tolerating many smaller attacks and sending a clear signal that there will not be a collective Article 5 response to them is simply bad policy.

Consider, too, that Russia would never be able to get away with flying over NATO skies and dropping leaflets of hostile disinformation by the millions onto NATO populations. It could never get away with doing so once or once in a while, let alone consistently and during sensitive times of pivotal political decisions or unrest in the targeted countries, and yet this is exactly the cyber-equivalent of what Russia is getting away with against NATO’s most significant member states and many of its smaller ones, too. And while Russia sending in Spetsnaz special forces to steal sensitive information from U.S. bases in Alaska or use physical weapons to sabotage or destroy government computer systems in Lithuania would be viewed automatically as an Article 5-triggering act of war, the same results over and over again from several years of unrelenting cyberwarfare are not, even though this has done more damage to NATO than any Soviet Army did throughout the decades-long Cold War. This is, in part, because of NATO: the USSR and then Russia did not dare use armed force to attack any NATO state for fear of that explicitly guaranteed Article 5 collective response (even when NATO-member Turkey shot down a Russian military jet over Syria in 2015).

Yet when it comes to cyberwarfare, NATO is practically inviting Russia to attack and get away with it, with the Alliance quite consistently demonstrating its inability and unwillingness under its current framework to respond collectively to Russian cyberaggression. As noted in the aforementioned UK Russia report, “Russia is not overly concerned about individual reprisal” against its aggressive acts, most certainly including its cyberattacks, with even the U.S. clearly inspiring no fear.

Language can often be tricky, and terms like “war” should never be thrown about lightly. But with the advent of the internet and the realities of the modern world, NATO cannot become complacent with preventing traditional warfare while failing to adapt to cyberwarfare. Pretending cyberwarfare is not war and allowing cyberwarfare in real-world practice to be kept out of NATO’s Article 5—leaving individual members states flailing independently and ineffectively against a determined, capable, and organized de facto enemy content to stand down its conventional forces against NATO while unleashing its cyberunits upon it with impunity—has not discouraged Russian cyberwarfare against NATO, it has encouraged it. Article 5 makes no exception for smaller armed attacks, and any serious collective cybersecurity defense should make no exception for smaller cyberattacks.

An Urgent Need for Drastic Reform

Throughout New York Times cybersecurity reporter Nicole Perlroth’s recent book This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends—the indispensable, terrifying, definitive account of the development of cyberwarfare and the mess in which we currently find ourselves: a true must-read for anyone hoping to understand how grave is the danger we are facing at this very moment—a constant theme is that we need paradigm shifts in the way we approach cybersecurity, whether the private sector, government, or individual citizens collectively. You can tell she was having trouble sleeping while researching and writing her book, and we should be, too.

At several points in her book, Perlroth notes that the U.S. in the past rebuffed attempts to discuss some sort of international cyberwarfare convention or treaty, feeling it was the undisputed champion in the cyberarms race and not wanting to give up that advantage. That ship has long sailed, and just in the last few years a number of rival and hostile governments have greatly managed to shrink, maybe even close, that gap, and with Western countries far more wired than their main rivals and enemies, they are far more vulnerable—with far more to lose—to cyberwarfare.

As FBI Director Christopher Wray recently lamented, the threat cyberwarfare poses to the West has “a lot of parallels” to the threat of terrorism after 9/11. Echoing Wray, former CIA director and secretary of defense for President Barack Obama, Leon Panetta, warned in a recent interview conducted by Perlroth that he fears we will not do what needs to be done before a “Cyber Pearl Harbor” may cripple us.

Perlroth warns at the end of her book’s epilogue that “many will say” that “these…critical assignments of our time” to deter and defend ourselves from cyberwarfare “are impossible, but we have summoned the best of our scientific community, government, industry, and everyday people to overcome existential challenges before. Why can’t we do it again?…We don’t have to wait until the Big One to get going.”

How to Revise Article 5 and the NATO Treaty Overall

Considering that the West’s main advantage over Russia is that people like the West a lot more than Russia—manifesting itself in close diplomatic, military, and economic ties about which Russia can only fantasize—the easiest way for the West to face and counter this dire and worsening cyberthreat from Russia is by leveraging its alliances, and, more than anything else, this means involving NATO and involving it in a big way.

U.S. President Joe Biden himself penned a recent Washington Post op-ed in advance of his upcoming trip to Europe for a NATO summit and to confront Putin face-to-face, writing: “In Brussels, at the NATO summit, I will affirm the United States’ unwavering commitment to Article 5 and to ensuring our alliance is strong in the face of every challenge, including threats like cyberattacks on our critical infrastructure.”

He can do that by proposing to strengthen Article 5 itself.

With Russia’s rampant cyberwarfare only intensifying and its clear pattern as a bad-faith hostile actor, a paradigm shift in the international system for deterring cyberattacks is absolutely necessary. Since NATO is the premier defensive alliance of the West, formalizing cyberwarfare’s relationship to Article 5 is a necessary leap forward on this much-needed path and the only way forward for NATO to maintain credible collective defense as the twenty-first century progresses.

To this end, “or cyberattack” must be added after each instance of the words “armed attack” in Article 5 (e.g., “The Parties agree that an armed attack or cyberattack against one or more of them…” [emphasis added]).

As other Treaty articles have (sometimes subsequently) modified the scope of Article 5, I propose the following definitions of cyberattack are added in a new Article 15:

Cyberattack in relation to Article 5 shall be defined as I.) any attack in which damage as opposed to non-weaponized espionage is a purpose or II.) widespread, deep, extreme cyberespionage (determined on a case-by-case basis). Smaller-scale theft of secrets will remain an act the response for which is reserved for normal counterintelligence and/or law-enforcement operations and will be considered just espionage and not applicable to Article 5 as a cyberattack in this context, but any cyberoperation in which damage apart from access to information is the purpose—I.)—shall be included such that the damage involves:

- a.) Actual damage to people or property, including physical but also the destruction or corruption of data or intellectual property

- b.) Any attempt to weaponize any non-public information, data, or disinformation, including for use through

- i. Military application

- ii. Extortion

- iii. Character assassination

- iv. Attacking institutional or organizational credibility

- v. Influencing any kind of negotiations (including private sector)

- vi. Coordinated tactical and strategic propaganda, misinformation, or disinformation to shape public opinion in an artificial, amplified way outside the bounds of authentic media and public/diplomatic engagement

- vii. Sharing with hostile third-party actors who engage in any of the above

- c.) Threats to engage in any of these with or without demands

The eligible perpetrators can fall in one of two categories:

- 1.) State or state-sponsored, as defined below:

- Any government-conducted, -sponsored, or -assisted cyberattack that engages in the above that targets any:

- i. Part of any of Party’ government or NATO organizational entity

- ii. Individual working directly or as a contractor for any Party government or NATO entity

- iii. Party’s critical infrastructure (including power plants, utilities and water infrastructure, hospitals and healthcare facilities, defense industry entities, mass communication and internet bodies and infrastructure, civil air and transportation bodies and infrastructure)

- iv. Party’s political party organizations and staff

- v. Party’s news media outlet or its journalists/staff

- vi. Party’s private sector or corporate or non-profit/NGO or private educational entities or their staff

- vii. Party’s citizens or residents or their spouses/dependents residing in a Party’s territory

- viii. Non-Party entities/staff operating in the Parties’ territory that would otherwise fit the above descriptions

- ix. People or entities in an attempt to influence any of those individuals or entities outlined in i.-viii. (e.g., their friends, families, or organizations/businesses to which they have ties)

- Any government-conducted, -sponsored, or -assisted cyberattack that engages in the above that targets any:

State governments sponsoring or assisting such acts may be included in any Article 5 response in part or in full.

- 2.) Non-state actors at an organizational level without state support, as defined below:

- Any terrorist group or other organization (official or de facto) that engages in 1.) i.-1.) iv. above. 1.) v.) and after would be the responsibility of normal counterterrorism or law enforcement operations unless the cyberattack is of a large scale.

This crucial definition of cyberattack allows more traditional espionage to stay out of discussions of cyberwarfare for collective defensive purposes while making clear the singular degree of the SolarWinds operation or anything like it will not get such a pass. It also means there will finally be a way to effectively counter and deter the massive weaponized disinformation campaigns conducted by Russia while also protecting citizens, including journalists and cybersecurity staff, who are on the front lines of this war.

While the Alliance is free to decide how it wants to respond when using Article 5, in many of the situations, appropriate coordinated cyberattacks coming from all of NATO’s member states would be the most conceivable and likely response except for far more serious cyberattacks.

Conclusion: Expanding Article 5 Is Necessary and Overdue

The early twenty-first century’s second decade has been something of a Wild West, with Russia emerging as the biggest beneficiary in terms of cyberwarfare as defined above. While China has also benefitted in terms of massive espionage and acquisition of Western intellectual property, it is Russia that has used the lawlessness of the cyber domain from a collective security standpoint to engage in the most egregious acts (most recently and most notably with the unprecedented SolarWinds) and ransomware attacks), acts that could easily be defined as hostile acts of war.

The time for lawlessness is over, and, with no statute of limitations on cyberattacks and the just-proposed framework not precluded by the current NATO treaty, NATO would be in its full rights (and is overdue) to invoke Article 5 against Russia now for its cyberwarfare so that Russia’s cyberwarfare will cause Russia far more pain than any damage it inflicts.

This has not been the case, but it must be.

Revising NATO’s Article 5 as suggested herein (leaving aside invocation) will not only clarify the rules for NATO enemies and rivals, but also for the members of a NATO Alliance itself that is in desperate need of clarity and strength on this issue. It will also make NATO once again an alliance that instills fear in the minds of Russian leaders (as it did with Stalin and subsequent Soviet leadership) who would engage in reckless acts of aggression against NATO or its states, even if “just” through cyberwarfare.

Member states recognizing that they are in a state of war—cyberwar, but still war—with Russia and unambiguously making cyberwarfare a key plank of the Alliance’s main collective defense mechanism is essential, then, to keeping NATO the force for deterring aggression it has been for many decades.

Projecting such strength, both on paper and in practice, will serve as a real-world check against further Russian cyberattacks when inaction and lack of clarity has not, enhancing the security of every NATO member state and perhaps even eventually forcing Russia to a point where productive engagement, not adventuristic brinksmanship, is its chosen priority.

© 2021 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

See Brian’s related review of one of the most important books on national security to come out in years, Nicole Perlroth’s groundbreaking This is How They Tell Me the World Ends; Also see my related article on the UK Parliament’s singularly excellent Russia report and my discussion as a member of a panel with author and Senior International Correspondent for The Guardian, Luke Harding, on Russia’s bad behavior

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!