As we are confronted with horrific wars even in 2023, a look back at how the Romans conceptualized peace may be instructive.

By Brian E. Frydenborg (Twitter @bfry1981, LinkedIn, Facebook, Substack with exclusive informal content, my Linktree with all my public links/profiles) November 7, 2023, excerpted from The Roman Republic in Greece: Lessons for Modern Peace/Stability Operations, Chapter 10 in the 2018 textbook, Global Leadership Initiatives for Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding, itself adapted and updated from my 2011 graduate school paper The How Behind Roman Pax: Selected Roman Operations Aimed at Establishing Peace and their Lessons for Modern Peace Operations – PDF here); because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed one million content views on January 1, 2023, but I still need your help, please keep sharing my work and consider also donating! Real Context News produces commissioned content for clients upon request at its discretion. Also, Brian is running for U.S. Senate for Maryland and you can learn about his campaign here.

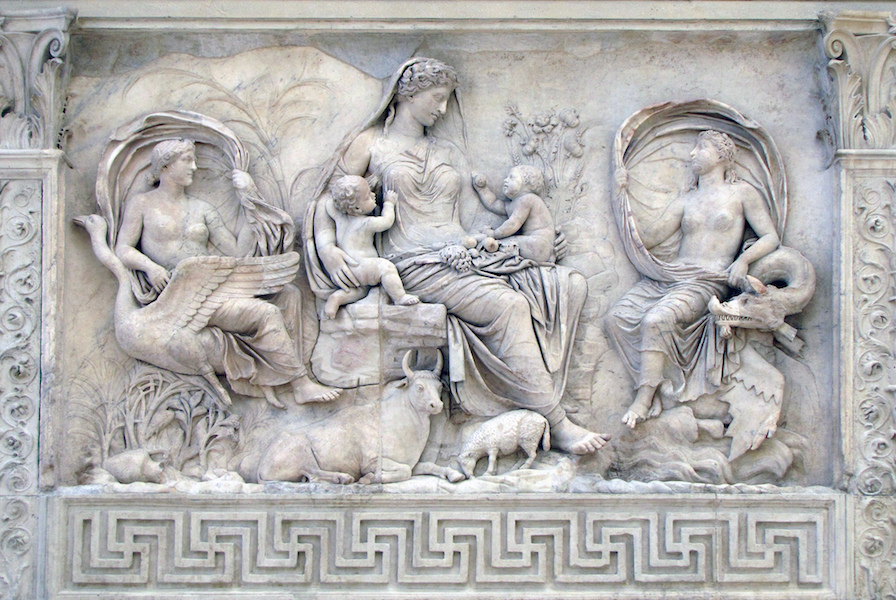

The Concept of Roman Peace

Contrary to popular and Hollywood-style views of Rome, Romans were not all warmongering imperialist murderers, rather, peace was highly valued and praised in Roman society and many Romans had sophisticated views of peace (Goldsworthy 2016b, pp. 10, 12-13). Inevitably, any view of peace is tied to views of war; without one, a definition of the other is meaningless. Just as right and wrong, rich and poor are terms that can exist only relative to each other, war and peace will always be related to each other. Today, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) includes “Freedom from civil unrest or disorder; public order and security” as the first definition, and another definition is “Freedom from, absence of, or cessation of war or hostilities; the condition or state of a nation or community in which it is not at war with another; peacetime” (OED Online). Other OED definitions include “a state of friendliness; amity, concord” and “stillness, quiet.” It notes the origin of the word is from the Latin word pax, also meaning peace. Though the modern Western “notion of peace [is] the child of Roman pax,” it is important to note that there are significant differences between how the Romans conceptualized peace and how the modern world does the same (Barton 2007, p. 245). The Latin word pax, like other important Latin words, has two opposite elements that form the range of the potential use of the word, these two meanings “poised…on the two opposite poles of a balance beam” in a figurative sense, as “[p]ax (peace) for the Romans could be a form of justice or a form of mercy; it might be a type of covenant or it might signal the absence of any contractual relationship” (p. 245). Thus the same word might give or take, bestow or impose. It can have a “light” or “dark” meaning, yet the “[m]odern English [word ‘peace’] suppresses the ‘darker’ meaning of Roman pax, or subsumes the ‘darker’ meaning in the ‘lighter,’” so that “the non-contractual aspects have been assimilated into the contractual” (p. 245). Words like “peace” and “mercy” today only give off a “gentle” vibe (p. 245). During the final, long period of civil wars that led to the collapse of the Republic and the establishment of the Imperial Roman state, the Roman definition of peace came much closer to the non-threatening, magnanimous, and forgiving meaning it holds for modern audiences, but for much of Roman history there was the aforementioned duality to its meaning. The duality existed, in part, because it took forceful, violent action on the part of Roman officials and armies, and the threat of such action, in order for anything approaching peace to exist. Retribution was a key element in peace and order, and domestic politics as well as international relations was a balancing act between opposing forces in the Roman world. Pax could also refer to social contracts; ultimately, much of Roman international relations (and domestic politics) can be seen as a series of social contracts, both formal and informal. Finally, one of the common uses of pax was in the context of pax deorum—peace with the gods—referring to the Romans’ relationship with the divine forces that governed the world (pp. 245-247).

For Romans, “war in official ideology was the restoration of order against those who had disrupted that order (Eckstein 2006b, p. 216);” in fact, it was “[t]he Romans [who] were the first to regard war as a form of legal self-help if another state had committed wrong by denial of justice” (Ziegler 2010, p. 972). It was something the Romans took very seriously, and it was, for much of republican Roman history, a matter of sacred religion. The beginnings of war involved special priests called fetiales who would approach the border of a foreign state that the Romans felt had done them wrong and would engage in a ritual called the rerum repitio, formally stating Rome’s grievances with the offending party or parties and giving that party or those parties a chance to make amends (even when the system changed as the Republic became larger and political envoys were used to declare war instead of priests, the envoys still regularly went through the motions of presenting Roman grievances and giving a chance and, importantly, time for atonement for them). This was how the Romans would show the gods and other nations that that their war, should the enemy not redress the wrongs committed against Rome, was a “just war” (bellum iustum) and that the Romans were not the ones disturbing the natural order. In fact, the war would be undertaken to restore the proper order of things. This was markedly different from other cultures of the time, cultures for which aggressive war for its own sake, for territory or plunder or glory, was almost never argued against, cultures which had no official mechanism to restrain their aggressiveness, let alone a sacred, religious one. And for the Romans, bellum iustum had to be defensive in nature, or it was not a bellum iustum. Cicero emphasized this when he wrote that

…wars are unjust when they are undertaken without proper cause. No war can be waged except for the sake of punishing or repelling an enemy…no war is deemed to be just if it has not been declared and proclaimed, and if redress has not been previously sought…

(The Republic 35, trans. 1998)

He also wrote that “…wars should be undertaken for the one purpose of living peaceably without suffering injustice” (On Obligations 1.35, trans. 2000). This comment in particular captures the civil order/social justice peace operations conception of a just peace, as in the absence of structural as well as physical violence. Cicero is the best extant articulation of the strain of Roman Stoic principles as applied to government and war and peace; the same principles are amplified by the poet Virgil in The Aeneid, articulating belief in Rome’s divine mission to bring civilization and peace to the world (though this is written after the case studies in question, after the Republic has given way to Augustus and the principate, an emperor-system dressed in the trappings of the Republic and honoring its traditions as the first phase of the Imperial government of the Roman Empire):

“Others, I have no doubt,

will forge the bronze to breathe with suppler lines,

draw from the block of marble features quick with life,

plead their cases better, chart with their rods the stars

that climb the sky and foretell the times they rise.

But you, Roman, remember, rule with all your power

the peoples of the earth—these will be your arts:

to put your stamp on the works and ways of peace,

to spare the defeated, break the proud in war.”

(6.980, trans. 2006)

The strain of Stoicism in Late Republican conceptions of peace always had undercurrents of universal brotherhood, promoted by wise, elected officials governing a free society through laws and wisdom that uphold the universal dignity and brotherhood all men share, and that to go against such principles and treat people unjustly is to violate the basic foundation of society and this universal law, is even to violate the gods themselves. Of course, this was the ideal; as in any ideal, practice would differ while still being constrained by the ideal.[1]

Though “the Romans measured war and peace against a very different yardstick of values than do contemporary Americans or Europeans” (Rosenstein 2007, p. 228), the Roman ideas of war and peace should be regarded as important for students and practitioners of peace/stability operations, in particular, because “[m]odern notions of ‘justice’ and ‘mercy’ are two keys to understanding ancient Roman notions of peace” (Barton 2007, p. 245).

At the heart of the concepts of both “peace” and “justice” for Rome was reciprocity (Barton 2007, 246). As Nathan Rosenstein (2007) points out, there was no United Nations or general concept of international law as exists today in the modern world (p. 228). Eckstein (2006b) will be heavily cited throughout this chapter partly to make the point that the ancient Mediterranean was a fiercely competitive political environment between states; all large states and medium were very aggressive and even many smaller ones, too. Much of this atmosphere comes from centuries of the Greek interstate political culture which dominated much of the Mediterranean. Thucydides, the ancient Greek historian today generally considered to be the founder of the “Realist” school of international relations, writing of his own era used what has become a famous phrase from a dialogue between Athenian and Melian representatives that “right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (History of the Peloponnesian War 5.89, trans. 1874/1996). The issue in question is not loot or glory, but simply survival. In a brutal “militarized interstate anarchy” such as that of the ancient Mediterranean, “fear dominates the decision making of most states” (Eckstein 2006b, pp. 49-50). Even when a state needs to behave defensively, “such defensive actions often take the aggressive form;” it was a world where if one state did not exploit another weaker one, that first state’s rival would exploit that other weaker state and then use its increased power to dominate the first state that hesitated (p. 51). Even the mere appearance of being weak invited trouble and aggression from other states. The “system,” and it probably should not even be granted that sophisticated a word to describe it, “works” whereby any weaker state must be severely punished by the larger state it challenges, for any positive result for the weaker state could encourage other weaker states to follow suit, or even join together against the larger state, or, in a worst-case scenario, the stronger state’s own subjects may conclude it is too weak to punish them and may rebel or even seek to overthrow said state. In such an environment, mercy encourages further challenges, so the “system” “works” when the strong state brutalizes and possibly annihilates the smaller state that challenges it, keeping other states in line and following the “rules.” In the case of the Athenians and the Melians, the Melians, after reaching out to allies of Sparta, Athens’ chief rival, did not submit to Athenian rule and were totally destroyed by Athens. Athens may not have even wanted to behave so brutally, but it felt it had no choice under the conditions of “the system.” Thus, the “system” encourages brutality as a necessary means of survival and pushes peoples and states that would prefer mercy to act against such inclinations. It was common for “state expansion…[to be] caused primarily by fear generated by pressing circumstances” (p. 56).[2]

NOTES

[1] For more on these themes, see Eckstein 2006b, pp. 216-229; Rosenstein 2007, p. 229; Clark 2011, pp. 3-4; Pangle and Ahrensdorf 1999, pp. 51-72; Adler 2007, pp. 310-312; Yakobson 2009; and Burton 2011, pp. 121-122, 333-334.

[2] For further detail on these themes, see Barton 2007, p. 246; Rosenstein 2007, p. 228; Eckstein 2006b, pp. 48-57; Goldsworthy 2016b, p. 59.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Adler, E. (2007, February-March). [Review of the book Caesar in Gaul and Rome: War in Words, by A M. Riggsby]. The Classical Journal, 102(3), 310–312.

Barton, C. A. (2007). “The price of peace in ancient Rome.” In K. A. Raalflaub (Ed.), War and peace in the ancient world (pp. 245–257). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9780470774083.ch14

Burton, P. L. (2011). Friendship and empire: Roman diplomacy and imperialism in the Middle Republic 335-146 BC. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139035590

Clark, G. (2011). Late Antiquity: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780199546206.001.0001

Eckstein, A. M. (2006b). Mediterranean anarchy, interstate war, and the rise of Rome. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goldsworthy, A. (2016b). Pax, Romana: War, peace and conquest in the Roman world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pangle, T. L., & Ahrensdorf, P. J. (1999). Justice among nations: On the moral basis of power and peace. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Rosenstein, N. (2007). “War and peace, fear and reconciliation at Rome.” In K. A. Raaflaub (Ed.), War and peace in the ancient world (pp. 226–244). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Yakobson, A. (2009). “Public opinion, foreign policy and just war in the late republic.”In C. Eilers (Ed.), Diplomats and diplomacy in the Roman world (pp. 45–72). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Ziegler, K. H. (2010). “War, just.” In A. Grafton, G. W. Most, & S. Settis (Eds.), The classical tradition,972-973. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.