An anti-monarchist reflects on what we have lost in our modern era: “an image of the splendour of the Kings of Men in glory undimmed before the breaking of the world.”

By Brian E. Frydenborg (Twitter @bfry1981, LinkedIn, Facebook), September 19, 2022

SILVER SPRING—I must admit from the outset that I never planned on writing an essay about this admittedly grand historical event. Yet the passing of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom the magnificent state ceremonies commemorating her passing pulled me in quite unexpectedly and, in spite of myself, I found I was filled with some rather profound (at least to me) thoughts on the whole symbolism of this moment, and the importance, at least, of that symbolism of perhaps not so much the institution of the British Monarchy here and now but of what it once was: one of the grand monarchies in world history, one that ruled over a vast empire, at times the largest and most powerful in the world for its time, even though for much of that time, the monarchy was constrained, and increasingly so over time as the British Parliament exercised more and more power over time at the expense of the monarchy.

Today, the day of the Queen’s funeral and interment, it seems so much more preferable to quote J.R.R. Tolkien—who himself was named by Queen Elizabeth II in 1972 (a year and then some before his death in 1973) a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) and suffered so much in the trenches as a soldier in World War I, surviving when many of his friends did not—than Churchill, who was an ardent acolyte of British imperialism and near-gleefully described shooting Sudanese from the days of his military service in the 1898 Battle of Omdurman in the era preceding World War I. In the Appendices of Tolkien’s magisterial The Lord of the Rings (spoilers to follow), after Aragorn becomes Aragorn II Elessar Telcontar, the king not only of Gondor but also of Arnor and thus the High King of the Reunited Kingdom of Arnor and Gondor, it is noted that he rises to heights for a human not seen in Middle Earth in literally thousands of years and not ever seen again after his reign of well over a century, with Tolkien beautifully describing him in his eventual passing as “an image of the splendour of the Kings of Men in glory undimmed before the breaking of the world.”

That line has been popping up in my head ever since the Queen’s passing.

I am not sure how many people realize this, but Elizabeth II was the last major living historical figure linked to a bygone era that was itself after the twilight, indeed, during the dusk, of the era of great kings and empires and their accompanying trappings.

The degree of global interest, attendance (of both “commoners” and world leaders), and splendour (to use the British spelling) of these ceremonies surrounding the Queen’s passing have not seen anything to rival it in a generous generation’s full lifespan: very few people are currently alive to be able to claim to have witnessed anything similar, from afar on television and let alone in person. The sights, sounds, and solemnity of the occasion is not like anything I have ever seen and I am forty-years-old. This must seem even more fantastical in the eyes of the younger rising generations.

The only other comparable institution to the British Monarchy today is the Roman Catholic Papacy, but as Francis has only been pope since 2013, Elizabeth as a figure of stature over time dwarfs him, as the Queen has reigned since 1952, longer than any monarch in British or English history. That says a lot for a kingdom that has existed for over one thousand years, since the 920s (and even longer if you go back to Wessex). With the pope, there are no marriages or balls even if there is ceremony and ostentation.

In many ways—though hardly all—Elizabeth’s institution and her carrying out of her royal role was looking backwards in time, emulating and carrying on the literal symbols of the monarchy—titles, crowns, scepters, etc.—that came from generations past, when such things were far more common, the way of the world. In many ways, she and the monarchy itself lived in the past and was the living past presented to us in the present: to quote Tolkien again, “an image of the splendour of the Kings of Men in glory undimmed before the breaking of the world.”

To be clear, it is truly a blessing that the age of great monarchies wedding the state and religion together to terrorize the masses, ruling from inherited privilege over vast swath of unconsenting populations, some conquered by seats of power continents away, is no more. To quote the late great Englishman and British citizen turned American, Christopher Hitchens, the World War I era was “the greatest fall of monarchies in history,” and even Princess Elizabeth (before she was queen) was born just after this era (and a few years after the peak of the British Empire’s power and extent, today just a shell of that), but, again, to be clear, in many ways she and her institution sought to represent much from that era, ever gazing back upon it to present an image of its legacy to the present.

Charles III will never equal the stature of his mother for numerous reasons, and, I am certain that—not wanting to even attempt to outshine his mother—he will not have his own passing commemorated with nearly as much fuss as that of this mother. Perhaps the bloated Saudi monarchy, as contrived and “new money” as it is, may try to match the expense when the current king passes, but that would certainly not match Elizabeth’s passing’s ceremonies in gravitas, nor in the degree of awe and respect felt by much of the rest of the world. For a sad comparison to the current royal sendoff, consider the comparative whimper with which former Soviet Premier and President Mikhail Gorbachev—once a giant on the world stage and a revolutionary leader of the second most powerful nation then on earth—was laid to rest in Russia exactly one week before Elizabeth’s death.

As for Elizabeth herself, in her lifetime, we shall not see her like again. And though numerous other members of the British royal family brough much scandal upon themselves, throughout it all, Elizabeth never sullied herself within these scandals, managing to stay above them. As for her being a symbol of the aggression, conquests, and rule all soaked in blood of an aggressive empire, of the rule of royals instead of people ruling through democratically-elected representatives, and of the problems with the modern British monarchy, more than any of her predecessors, she bears the least responsibility for the sins of empire and autocracy. As this Irish-American author is happy to admit, the Queen is the first and only British or English monarch to offer anything even close to an apology for the evils the English and British have inflicted upon the Irish people, perhaps the first people to be colonized in a modern sense (if one doesn’t count the Crusades) and certainly the longest-suffering people under colonialism, a colonialism that began in 1169 and still persists to this day. As a result, even leaders of Northern Ireland’s Sinn Fein—the longtime Irish political party that was in the past the political wing of the terrorist Irish Republican Army that conducted insurgencies against British rule in Ireland—offered appreciative remarks (Michelle O’Neill: “Personally, I am grateful for Queen Elizabeth’s significant contribution and determined efforts to advancing peace and reconciliation between our two islands.”) and urged supporters to be respectful in the wake of her death. Even Sinn Fein and Irish Republic officials, as well as Catholic clergy, attended her state funeral today; this would have been unthinkable after the death of (nearly) every past British or English monarch.

So though she was a largely symbolic leader, she made real achievements of substance.

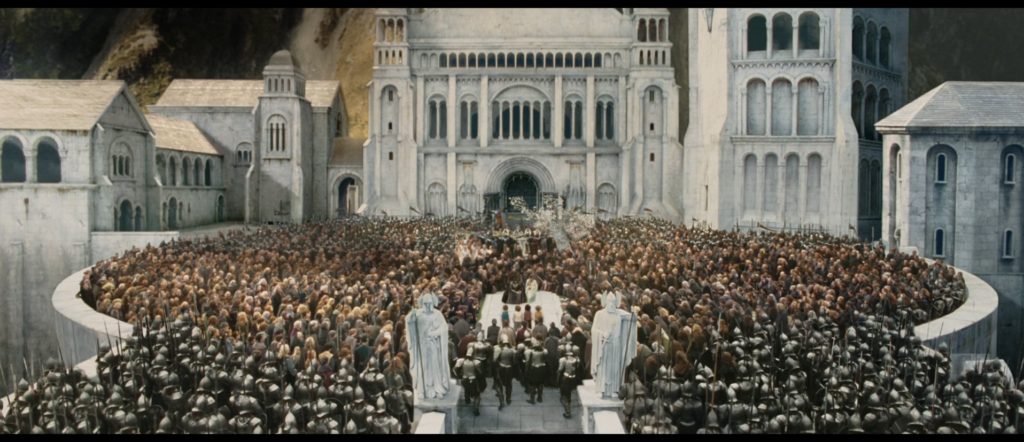

Is monarchy in its historical sense an evil? Undoubtedly, yes, a backwards horror from a time when humans were regarded largely as property and blood flowed as easily as torture and theocracy. And yet, in our far more democratic era, where in many places the masses have rightfully risen and formal aristocracy is thankfully no more, democratization of politics has led to a dressing down of ceremony, architecture, dress, art, music, literature… pretty much everything. Gone are the days of royal balls and weddings, we will have to settle for the fake ones in Game of Thrones or Bridgerton or historical shows like The Tudors, Versailles, The Great, and other king-and-queen focused shows and movies (my favorite scene of such is Aragorn’s coronation as Elessar in The Return of the King, for what it’s worth).

There is something we as humanity are collectively are losing knowing the grandeur, regality, and ornateness of the great kings and queens and emperors and pharaohs of history, their courts and lives and events—are, simply, more or less gone. The ancient ruling institutions that are either gone or diminished have often been responsible, however problematic the costs or means of production, for creating some of the greatest artistic achievements in arts, architecture, and fashion that are now forever a thing of past creation or fantasy. The type of formality and levels of etiquette and politeness they embody are essentially gone, too: we are ruder and more familiar culturally than any time in recent centuries.

Today, there are no more new pyramids, no new Roman Colosseum, no new imperial palaces, no new larger-than-life statues like the relics we see still standing today or remnants of which we see in museums (and that is not even getting into the many more that were destroyed and exist only in the history books), no new grand cathedrals or temples. These were all monumental achievements in human history, their modern successors far simpler and blander, and there is a sadness in knowing that part of part of our history is now relegated to history’s dustbin, but I wouldn’t have it any other way: better the oppression, massive concentrations of power and wealth, titanic scale of war and death, feudalism, imperialism, colonialism, and slavery that produced them are gone.

But that doesn’t mean we cannot separate the art from the artist and mourn the loss of the ability to produce such things, for what society would rightfully spend so much public money on such ornate but unnecessary things with all the problems we now face and with governments finally existing in an era where they must respond to the needs of the people or get voted out of office or overthrown, at a time when people feel loyalty not to monarchs appointed by “god,” but to their own sense of worth as individuals? The answer is none, no society would choose to fund a Versailles or Pharaonic- or Mayan-style pyramids today and for good reason.

Has, and is, the coverage (at least in English-speaking media) been wildly overblown? Yes. To channel the spirit of Hitchens (who once remarked: “It’s always struck me as rather bizarre that there’s this cult in the United States of English royalism—just the sort of thing that I left England to get away from.”), I could do without 95% of the coverage I’ve seen of the British royals in my lifetime: the absurdities of endless coverage of Diana in life and death, the royal babies and marriages and silly scandals, the endless television specials and magazine covers (every time I am at a supermarket or drug store, they are there), and even much of the near non-stop coverage in between her death and her funeral (when major developments in Russia’s brutal colonialist imperialist war in Ukraine occurred and should have been covered with a higher priority).

Having said all that, I appreciate the coverage of her death the day of, the day after, and during the funeral. I appreciate the person who was Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and how she carried out her duties. I appreciate the grandeur of an era that is hard to comprehend even for me as a historian, and even more the horrors inflicted upon us by the rule and fiats of theocratic autocrats draped in fine robes with bejeweled crowns, but, at this moment, when the last true link to that era passes, I choose to reflect on the unique if costly beauty of that era that has, with Elizabeth II’s passing, now mostly been consigned to memory. Her funeral and the related proceedings are truly “an image of the splendour of the Kings of Men in glory undimmed before the breaking of the world,” and we should all reflect on that splendour (I’ll again keep the British spelling here) and its problematic beauty in all its glory, presented here one last time for all the world to see.

© 2022 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see Brian’s eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed half-a-million content views on 8/27/22 and 600,000 on 9/8/22!!

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!