Apart from other thematic ways I already discussed that Putin today is repeating Stalin’s mistakes from the disastrous launching of the 1939 Soviet invasion of Finland, here are a number of other illuminating similarities between the two debacles

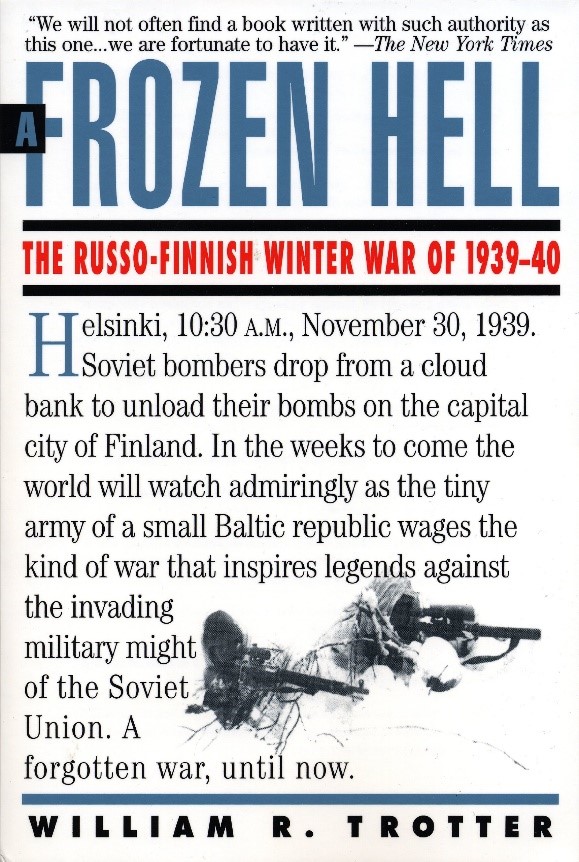

(Russian/Русский перевод) By Brian E. Frydenborg, June 7, 2022 (Twitter @bfry1981; LinkedIn, Facebook); this is one of a series of articles excerpted and/or adapted from Brian’s May 23 Small Wars Journal article, Bungling the Prewar and First Moves in Finland 1939 and Ukraine 2022: A Comedy of Errors for Stalin’s Soviet Union and Putin’s Russia, Respectively, his deep-dive analysis on the parallels between the 1939-1940 Soviet-Finnish Winter War that was inspired by his reading the beginning of one of the definitive English accounts of this war—William Trotter’s A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40 (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1991, 283 pages; for sourcing, assume all uncited information comes from Trotter’s book but quotes will be given a page number or numbers in parentheses and anything from another source an external a link; in some instances, when I have written in detail about something, I may link to my own work, in which you can find many external sources backing up what has been stated). This conflict is especially timely as Finland seeks to join NATO in light of Russia’s recent imperialist aggression.

Other articles excerpted and/or adapted from the May 23 Small Wars Journal article:

- May 23: A Terrifying Comparison Between Putin and Stalin

- May 25: A Brief History of Russian and Soviet Genocides, Mass Deportations, and Other Atrocities in Ukraine

- May 31: “Banderites”: What Russia Really Means When It Calls Ukraine Nazi and Fascist

- June 2: How Delusions of Phantom Fascists Duped Stalin in 1939 and Putin in 2022

- June 5: Moscow’s 1939 Finland Hubris Repeats Itself in Ukraine in 2022

SILVER SPRING—Apart from the main themes I have already discussed in this series (hubris and delusions about “fascists”), there are a number of other noteworthy similarities between the two conflicts apparent from Trotter’s early chapters.

One major parallel involves command and control, combined arms coordination, and communication. Notes Trotter:

Nor did the Red generals appreciate the amount of trouble the Wehrmacht [i.e., German Military] had taken to perfect tactical coordination between the component arms, to ensure a reliable and redundant network of communications, and to instill in its frontline commanders a sense of drive and individual initiative. Those very qualities, if displayed in the Red Army, were more apt to earn a man a trip to the gulag than a pat on the back. Many of the battalion and regimental commanders who would lead the Russian attacks were by this time little more than groveling flunkies whose every battlefield decision had to be seconded by a political commissar before orders could go to the troops. (36)

As for the Ukraine war today, it has been amply noted (including by me) that these elements have been a resounding disgrace for the Russian military: troops using easily trackable sim cards in their cell phones, thus revealing their positions/relative strength; troops communicating with totally unsecured and easily monitored methods, such as those cell phones; a general getting killed because Ukraine could track his phone calls; command posts getting hit regularly by Ukraine; a lack of coordination overall and between different military branches, including air support that does not arrive; poor, mercurial, and unclear command structures (if a recent report that Putin may be micromanaging things on the battlefield, this only makes this last problem exponentially more insurmountable); and the list could go on…

For another similarity, Stalin was fairly isolated, having not-too-long-before committed a series of massive purges of the Soviet military, intelligence, political, and bureaucratic leadership. To say that the survivors and replacements were hesitant to tell Stalin something that he did not want to hear would be a massive understatement. In particular, his main diplomatic man in Helsinki, Vladimir Derevyanski, was a constant source of wildly rosy, inaccurate views of the real mood and situation on the ground in Finland.

Putin, too, especially in this pandemic era, is a pretty isolated leader: his long meeting tables with himself and the guest sitting on opposite ends and the vast separation from his council at major government meetings are only the most obvious representations of this isolation. Along with this isolation, it is almost certain that he has been getting from advisors afraid to tell him the truth a fantastical version of the situation on the ground on Ukraine on which he based his plans and adjustments and on which much of the massive failure of Russia during the early phase of the war can be blamed. His senior advisors, like Stalin’s inner circle after the purges, nervously fear being imprisoned or worse (as is already happening) and very likely adjust what they tell Putin accordingly; the same can be said for many of their sources.

For Stalin’s man in Helsinki, Derevyanski, we can substitute Ukrainian Viktor Medvedchuk as Putin’s man in Kyiv, whom I have profiled before. Like Stalin’s Derevyanski, Medvedchuk is thought for years to have been providing Moscow with bad information that is far from the reality on the ground, contributing to the gross misjudgments of Putin’s that have the world in the situation with Ukraine that it is now. Medvedchuk is so close to Putin that the Russian president is even godfather to the man’s daughter; her godmother is the wife of Putin’s temporary successor to the Russian presidency from 2008-2012, Dmitry Medvedev, now the top official on the Russian Security Council after Putin himself (notably, Medvedchuk’s wife—Oxana Marchenko—seems to have had financial ties through a super-shady Ukrainian “businessman”—Igor Anopolskiy—who was seriously involved with the scandal-plagued, ill-fated Panama City, Panama, Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower, a hub of money laundering for the Putin-allied Russian mafia and Latin American drug cartels alike).

One of the longtime leaders and orchestrators of the pro-Russian political faction in Ukraine, Medvedchuk has been trying to hand Putin influence in Ukraine through his corrupt politics and media operations, most recently in Ukraine’s parliament as the main opposition figure to Zelensky. The coalition party he leads—Opposition Platform—For Life—runs multiple disinformation television stations in Ukraine that are like a mix of Fox News and RT (one of the Russian government’s top disinformation/propaganda outlets), on a mission to undermine his political foe Zelensky and the West while boosting Putin and Russia. U.S. intelligence has said Medvedchuk is part of a plot to overthrow Zelensky, and he has been charged with treason in Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, he fled his house arrest, only to be captured by Ukrainian forces last month, after which Zelensky’s Instagram account displayed this photo of Medvedchuk in handcuffs:

If people spend so much time creating an alternate reality, they might actually just believe in it, and while it is impossible to tell from the outside to what degree Putin and his minions believe what they profess even as it changes so often, reality has certainly to a significant degree eluded them.

A further interesting parallel, this one between Finland then and Ukraine today, involves their preparations for war. The political leadership of both nations professed publicly that they did not take Moscow’s threats entirely seriously, that it was bluffing as a negotiating strategy more than actually preparing for a serious war. In the case of the Finns, this mentality very much characterized the actual beliefs of Finnish Prime Minister Aimo Cajander, President Kyösti Kallio, Foreign Minister Eljas Erkko, and the rest of the Finnish leadership team, with the main exception being Gustav Mannerheim, the man who would actually lead Finland’s military effort during the war.

With Ukraine today, at least one telling interview with CNN’s excellent Matthew Chance convincingly supports the idea that while Zelensky publicly downplayed the threat of a Russian invasion, he was privately deeply worried one was coming and did not only downplay the threat to help Ukrainians keep calm, but by design to bait the Russians into a sloppy, rushed, overconfident approach to their invasion (I would say this claim of Zelensky’s is well-supported by how events have played—and continue to play—out).

In the cases of both countries, though, the military leaders were planning meticulously what to do in the event of an invasion launched by Moscow, well aware of their relatively small size and fewer resources available (in contrast, the Soviet planners never thought they might be fighting a war against only Finland; their planning had envisioned much grander conflicts, ones in which Finland was quickly co-opted or occupied itself by a major Western power and used as a staging area for invasion). Whatever Finnish or Ukrainian politicians were saying, whatever they meant, then, the military folks in both Finland and Ukraine took the opportunities to plan, train, and prepare during the years in the run-up to the actual invasions very seriously and to incredibly good effect; to quote Mark Hertling, Commanding General of U.S. Army Europe and the Seventh Army in 2011-2012, “during my assignment as commander of U.S. Army Europe, I also spent a significant amount of time with the Ukrainian Army and was amazed as I watched them grow in professionalism and effectiveness.” He had also seen them over the years in other capacities, which makes that already considerably weighty statement carry even more weight.

Sill another situation where commonalities are present is a related similarity involving how both Finland and Ukraine would explain their position to the rest of the world. In this vein, the following passage of Trotter’s on Mannerheim’s and his subordinates’ strategy struck me powerfully:

In the long run, Finland’s only real guarantee of continued existence was the conscience of Western civilization. Finland, it was hoped, would be regarded as a vital outpost of everything the Western powers stood for, and as such the country would not be allowed to vanish from the map. Thus was born a strategy designed to enable Finland to hang on long enough for outside aid to reach it. (39)

Both Finland and Ukraine had plans, too, for continuing to fight against Russia even under occupation and/or if the West did not come to its aid or aid came too late to prevent the fall of the country to the invaders. But it is the overlap from Ukraine today with the above-quoted themes that is most striking, not least in terms of the rhetoric we are hearing today from Ukraine matching Finland’s characterization in 1939-1940 of itself as the defender of Europe and the West and its values—the defender of freedom and democracy—in the face of rampant aggression from Moscow.

A final key parallel involves how the wars began. Ever the propagandists, the Soviets even went through the trouble of a false flag attack (an attack committed by one party but blamed on another for propaganda purposes), firing artillery barely into their own territory—perhaps some 800 meters from Finland’s border—on November 26, 1939, then claiming it was the Finns who fired to start the war:

The…shots, [Khrushchev] claimed, were set up by Marshal of Artillery Kulik, a brutal and cretinous NKVD general whose military incompetence would cost the Soviet Union terribly during the first weeks of the German invasion. It is logical to assume that Zhdanov and Stalin both knew of the fabrication and condoned it. Khrushchev deals coyly with the question of who fired first at whom: “It’s always like that when people start a war. They say, ‘You fired the first shot,’ or ‘You slapped me first and I’m only hitting back.’ There was once a ritual which you sometimes see in opera: someone throws down a glove to challenge someone else to a duel; if the glove is picked up, that means the challenge is accepted. Perhaps that’s how it was done in the old days, but in our time it’s not always so clear who starts a war.” (22)

This seems to be similar in spirit to how Putin started his massive late-February 2022-through-the-present escalation against Ukraine: shelling from his Russian military and the pro-Russian separatists Russia supports in the Donbas all across the main lines there, coupled with (nearly-certain-to-be) disinformation that Ukrainian forces were initiating escalation by firing intensely into separatist territory or even sending “saboteurs” into Russian territory (among other inane claims). The Ukrainians, far more credibly accusing Russia of lying and even carrying out a false flag attack, denied the relatively absurd claims that they as the far-smaller and far-weaker party—the one that wanted to avoid war—somehow managed to deliberately start the war and provoke the far more powerful party of Russia, to whatever inconceivable ends. After all, Zelensky has shown himself to be no fool and Moscow is the party here with a history of false flag attacks and gaslighting about its own roles in participating in various conflicts. The Biden Administration along with Boris Johnson’s British Government has rather deftly publicly called out Russia’s disinformation and false flag efforts preemptively and consistently, further undermining the Kremlin’s game plan to make the world think Ukraine was the aggressor and one-upping Putin on the information war front with an unprecedented, bold approach to releasing and sharing intelligence.

Moscow over the years seems to do far more than most nations to prove the old saying that “truth is the first casualty in war.”

Dumfounding Déjà Vu

What is crazy about all this is that this article and others in this series simply arose out of reactions to just the beginning of Trotter’s book on the Winter War.

One thing that is clear: in trying to understand the events between Finland and the Soviet Union in 1939, for Trotter:

Motives, true feelings, and lines of responsibility are not very clear at this level of the Soviet command even today. The whole Finnish campaign was an embarrassment to the officer caste, and even half a century later there is little discussion of it in print on the Russian side. (34)

Three decades after Trotter’s book was published, Putin’s pathetic execution of his war in Ukraine demonstrates clearly that there has been little serious high-level discussion or understanding of any sort in the Kremlin of the First Soviet-Finnish War.

See all Brian’s Ukraine coverage here

© 2022 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!