Looking at the geopolitics of Eastern Europe in 2022 and 1939 is both illuminating and disturbing

(Russian/Русский перевод) By Brian E. Frydenborg, May 23, 2022 (Twitter @bfry1981; LinkedIn, Facebook); this is the first of a series of articles excerpted and/or adapted from Brian’s same-day Small Wars Journal article, Bungling the Prewar and First Moves in Finland 1939 and Ukraine 2022: A Comedy of Errors for Stalin’s Soviet Union and Putin’s Russia, Respectively, his deep-dive analysis on the parallels between the 1939-1940 Soviet-Finnish Winter War that was inspired by his reading the beginning of one of the definitive English accounts of this war—William Trotter’s A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40 (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1991, 283 pages; for sourcing, assume all uncited information comes from Trotter’s book but quotes will be given a page number or numbers in parentheses and anything from another source an external a link; in some instances, when I have written in detail about something, I may link to my own work, in which you can find many external sources backing up what has been stated). This conflict is especially timely as Finland seeks to join NATO in light of Russia’s recent imperialist aggression.

Other articles excerpted and/or adapted from the Small Wars Journal article:

- May 25: A Brief History of Russian and Soviet Genocides, Mass Deportations, and Other Atrocities in Ukraine

- May 31: “Banderites”: What Russia Really Means When It Calls Ukraine Nazi and Fascist

- June 2: How Delusions of Phantom Fascists Duped Stalin in 1939 and Putin in 2022

- June 5: Moscow’s 1939 Finland Hubris Repeats Itself in Ukraine in 2022

- June 7: A Flurry of Telling Parallels Between the 1939-1940 Soviet-Finnish Winter War and Russia’s 2022 Ukraine War

Location, Location, Location: Geopolitics in Eastern Europe for Stalin (and Putin)

Setting the Stage

WASHINGTON and SILVER SPRING—On the first page of the first chapter, geography is, appropriately, discussed. Like Ukraine’s plains, the Karelian Isthmus that connects Finland historically to St. Petersburg—the tsarist capital since the time of Peter the Great, but renamed Petrograd during World War I, then Leningrad in the Soviet era, after Vladimir Lenin’s death—has been a pathway for invaders from both directions. In the case of the isthmus, this path was into and out of Russia and Asia on one side and Europe and Scandinavia on the other, and controlling such pathways was deemed vital to Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in the late 1930s as it is also by Russian President Vladimir Putin in the twenty-first century. Even in the 1930s, driving across the Isthmus from Finland’s border to Leningrad was simply a matter of a few hours (just thirty-two kilometers to its limits).

With Hitler’s outright and frothing hostility to the ideology of communism and to the Slavic people as a whole, and, to Russia’s West there being Imperial Japan (also intensely hostile to communism and expanding near Russia’s Far East), Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin eyed ostensibly neutral Finland quite nervously: though the Russian tsars ruled over Finland for a little over a century after the Napoleonic Wars, in the waning days of the Tsarist Russian Empire, Finns looked to overthrow an increasingly repressive Russian rule during World War I, some 2,000 Finns collaborating with Kaiser Wilhelm’s Imperial Germany during the war I and serving in their own unit in the Kaiser’s Imperial German Army. Just days after the 1917 October/Bolshevik Revolution began in Russia—in which Lenin and his communists seized power in Petrograd—Finland declared independence and Lenin was too distracted by bigger problems to not acquiesce three weeks later. Despite the efforts of Finnish communist with newly-Soviet Russian help to hold and expand power in Finland, during the Finnish Civil War of 1918, the Finnish communists were crushed by the opposing Finnish Whites with the help of forces from Imperial Germany. Not long after, the Finns would allow anti-Bolshevik Russian and British forces to launch attacks against Russian communists during the Russian Civil War, though the communists under Lenin would prevail in the conflict. He and his regime were bitter about losing Finland, and felt at some future point it could be brought back into the fold with little effort.

Some two decades later, with Stalin firmly in power and Lenin long dead, the new Soviet leader and his circle were concerned about another German threat: Hitler’s Nazi Germany, and that the Nazi Führer would be able to coerce a weak, unaligned Finland into being a base for a German invasion of the Soviet Union (Soviet Russia had coerced other parts of what was Russia’s disintegrating Empire into a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: the USSR) aimed at nearby and very vulnerable Leningrad, one of the USSR’s indispensable urban centers. The World War I-/Russian Revolution-/Russian Civil War-era multiple direct collaborations between Finnish and German forces against Tsarist Russia and both Russian and Finnish communists only made this concern more acute in the eyes of the communist Soviets.

Rather than some obsession with dominating and controlling Finland, Stalin seemed mostly concerned with looming Nazi expansionism (hardly an unfounded threat, as history would prove) and saw Finland’s geography in relation to Soviet territory and especially the all-important Leningrad as an unacceptable risk under the status quo in 1938.

Aggressive Negotiations

Thus, in April of that year, Stalin had his agents approach Finland with his security concerns. Unlike in 2022 with Putin and his “concerns” about Ukraine and NATO, Nazi Germany was one of the most evil regimes in world history and extremely expansionist as well as warmongering. And today, we know in hindsight (and, indeed, many at the time felt this too, including Stalin, who was off by just a few years) that Hitler very much had designs of conquest and subjugation for the Soviet Union and the Slavic peoples.

Considering all this, public professions of neutrality from Finland, even if sincere by the Finns, did little to comfort Stalin; he knew if Hitler were to try to force Finland into the Nazi German Reich, Finland would not be able to put up much resistance and Hitler could use Finland, then, as a base from which to attack the USSR, or, even without formal conquest, could compel Finland into an alliance with Germany and force it to support an attack or join in an attack against the Soviets.

But Finland possessed a number of worthless, unpopulated islands—used only by Finnish fisherman during summer—that provided excellent defensive positions for the naval approaches to Leningrad, and Stalin’s folks inquired about the possibility of Finland ceding or leasing the islands to the Soviet Union in order to expand its security perimeter.

Finland flat-out rejected the idea.

Almost a year later, in March 1939, the Soviets came back, offering some slightly-disputed Karelian borderlands in exchange for a thirty-year lease of five Islands near Leningrad. Considering the climate of 1939, this was quite a reasonable offer, based on realistic, pressing security concerns on the part of Stalin in light of a massive threat coming from, of all people, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Reich (again, contrast today with NATO’s defensive alliance led by U.S. President Joe Biden: needless to say, nowhere near equivalents; and Ukraine’s borders with Russia now are nowhere near as close as Finland’s was to a one of the largest and most vulnerable cities of concern for the Soviets, meaning there is nothing like a Leningrad-equivalent less than three-dozen kilometers away or even close to that distance).

The man who would come to lead Finland’s military through the war, Gustav Mannerheim, felt this deal was entirely reasonable, knowing how weak and ill-supplied his Finnish Army was (it did not have a single working anti-tank gun at this time). He was already a legend at the time: a distinguished veteran of high rank during World War I, the culmination of his service for the tsar in the last few decades of the existence the Russian Empire of which Finland was then still a part; the leader of the anticommunist Finnish Whites who led them to victory in their brief civil war against the Finnish Reds; and at this point in 1939, the head of the Finnish government’s Defense Council.

But Mannerheim was ignored by the Finnish political leadership, along with the Soviet Union’s offers. Still, the Soviets kept pressuring Finland over the ensuing weeks and felt themselves pressured in this spring of 1939, eyeing Nazi Germany nervously.

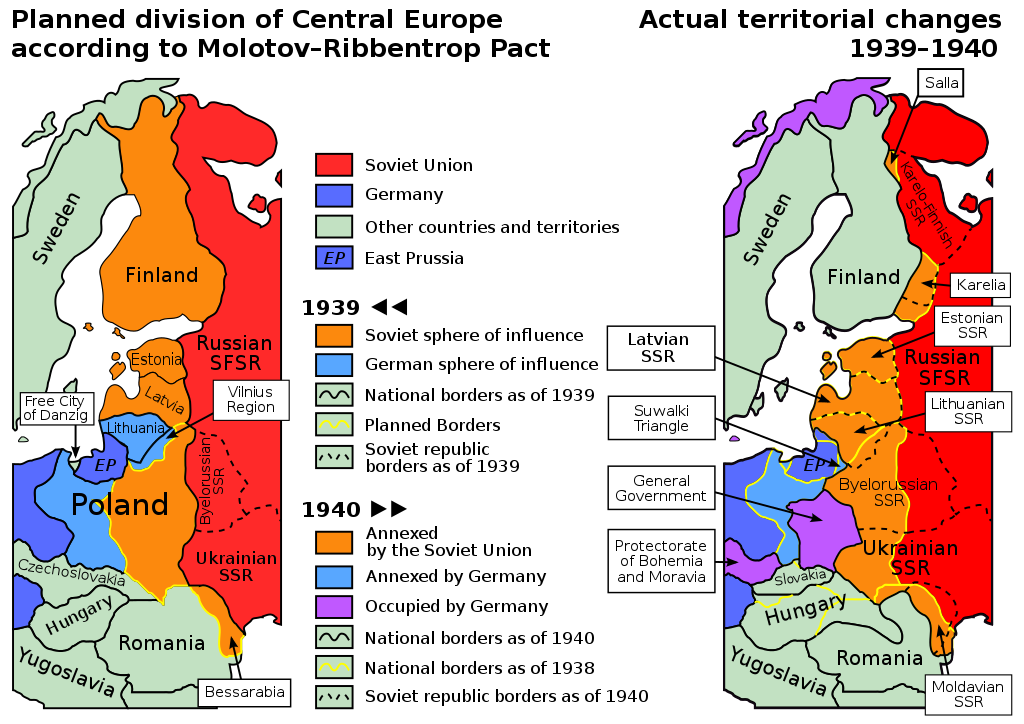

Hitler was indeed hostile, but was more focused for the moment on Central Europe, so the two enemies were able to come to the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in in August 1939, Hitler gobbling up western Poland soon after followed by Stalin gobbling up eastern Poland. Seeing the writing on the wall, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—each responding to invitations from late September through early October from the Soviets—soon after arrived in Moscow and would sign separate agreements making them de facto vassal satellite states of the Soviet Union, their freedom reluctantly signed away to avoid bloodshed faced with what they saw as a foregone conclusion.

Now, it was Finland’s turn. On October 12, Stalin put forward his demands to a high-level Finnish delegation that had been summoned to Moscow, explaining he could not tolerate Leningrad being so vulnerable by land and sea in the current climate. Therefore, he insisted on: a relatively large cessation of territory in the Karelian Isthmus approaching Leningrad; the destruction of all of Finland’s considerable fortifications on the Isthmus; four of the Finnish islands in the Gulf of Finland near Leningrad; most of the Rybachi (or Rybachy) Peninsula jutting out into the Barents Sea in the Arctic Ocean; leasing mainland Finland’s southernmost point, the Hanko peninsula, and its port there, where the Russians would establish a base manned by some 5,000 troops and supporting forces. In exchange, the USSR would give Finland some 5,500 square kilometers on Russia’s side of Karelia north of Lake Ladoga.

Compared to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—which de facto had to cede their entire sovereignty to the Soviet Union—Finland was getting off easy. And yet, the Finns also realized that the Karelian Isthmus demands meant essentially the eradication of Finland’s strongest and primary lines of defense against the Soviet Union. In addition, nearly all of Finland’s government leaders felt this was only the first series of demands before what they saw as the inevitable coming of later pre-hatched demands, which, after giving in on these first ones, the Finns would be powerless to resist. Some top Finish politicians and officials thought Stalin was bluffing or just setting a high position for haggling purposes, but Mannerheim, almost alone, thought the Soviets were quite serious and opined it would be wise to accommodate them.

As negotiations unfolded over the rest of October and into November, the Finns agreed to cede some of the Islands and a bit of the Karelian Isthmus, but rejected the Hanko proposition. Yet Stalin’s list of demands was no ploy and it was likely Stain was genuinely frustrated by weeks Finnish intransigence during negotiations. That the Finns were so stubborn over so many weeks actually led Stalin to believe that there was a distinct possibility they had already made some sort of backroom deal with the Nazis. For Trotter, lending credence that Stalin’s real and full aims were most likely what had been put openly to the Finns in October was that, years later in the final years of World War II and the early Cold War—when Stalin could easily have conquered all of Finland—he chose not to do so. But for Trotter, too, also clear was what the Soviets were demanding at gunpoint of Finland

came back to an irreducible case of right and wrong. Finland was a sovereign nation, and it had every legal and moral right to refuse any Russian demands for territory. And the Soviet Union, for its part, had no legal or moral right to pursue its policies by means of armed aggression. Even [Stalin’s successor] Nikita Khrushchev admitted as much, decades later, although in the next breath he rationalized the invasion in the name of realpolitik: “There’s some question whether we had any legal or moral right for our actions against Finland. Of course we didn’t have any legal right. As far as morality is concerned, our desire to protect ourselves was ample justification in our own eyes.” (17)

A final meeting in Moscow took place on November 9 between Stalin alongside his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, and the Finnish delegation in Moscow, Stalin reiterating his position and the Finns responding with the same small concessions they had put forward earlier. A yet-again surprised Stalin continued to plead with the Finns for an hour for further concessions, but to no avail. All seemed frustrated, but he bid the Finns a respectful farewell with handshakes and an “All the best.” It seems not with grandiose ambition, fury, or outrage, but a worn-out resignation to a regrettable yet necessary endeavor, that Stalin went from those almost cordial goodbyes to planning for a war to take his rejected demands by force.

A Disturbing Difference

I have already briefly mentioned a difference that I have found quite disturbing, one which I will now revisit in this conclusion. Looking at the precipice in 1939 just before Stalin invaded Finland, it is quite striking and unsettling for us today to realize that what Stalin was demanding—and apparently genuinely—of Finland pales in comparison to what Putin is demanding of Ukraine today. And this was even at a time of exponentially greater external security threats facing Stalin when compared with what Putin faces today in our present time of essentially no clear, present, imminent external security threats to Russia. To be fair, Stalin was far more brutal to Ukraine in his day, as noted herein, and Putin is not attacking Finland, but that is not the comparison I am making.

Still, again, let this sink in: Joseph Stalin, of all people, and at a time of terrible danger to the Soviet Union that he more or less foresaw, seems more rational and measured in 1939 than Putin does in 2022 at a time of far more security and stability.

I am not yet prepared to say what this means, but this reality makes me, to say the least, extremely uncomfortable.

At the same time, the First Soviet-Finnish War had an astonishingly good outcome for Finland, and, as I have explained in other work, Ukraine today is—to use the technical military term—kicking Russia’s ass, so there are also those two points to consider…

See all Brian’s Ukraine coverage here

© 2022 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see my eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here), and be sure to check out Brian’s new podcast!

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!