The smell of counteroffensive is in the air this spring in Ukraine as events in Kherson and Bakhmut will reverberate throughout Ukraine and shape that coming counteroffensive

(Russian/Русский перевод; Если вы состоите в российской армии и хотите сдаться Украине, звоните по этим номерам: +38 066 580 34 98 или +38 093 119 29 84; инструкции по сдаче здесь)

By Brian E. Frydenborg (Twitter @bfry1981, LinkedIn, Facebook) May 8, 2023; see earlier April 24 article Ukraine Crossing Dnipro River a Big Deal and General Assessment upon which this article greatly expands; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed one million content views on January 1, 2023, but I still need your help, please keep sharing my work and consider also donating! Real Context News produces commissioned content for clients upon request at its discretion.

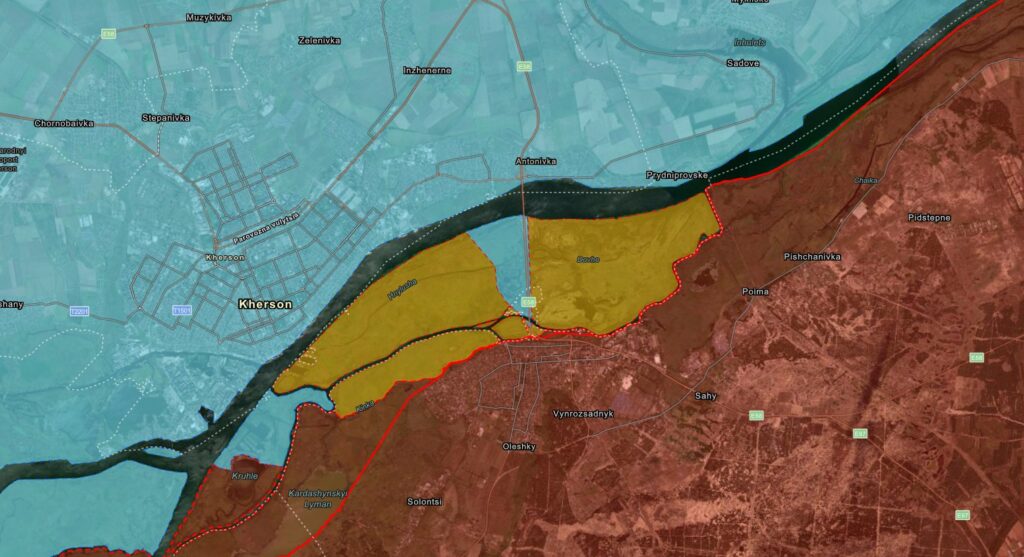

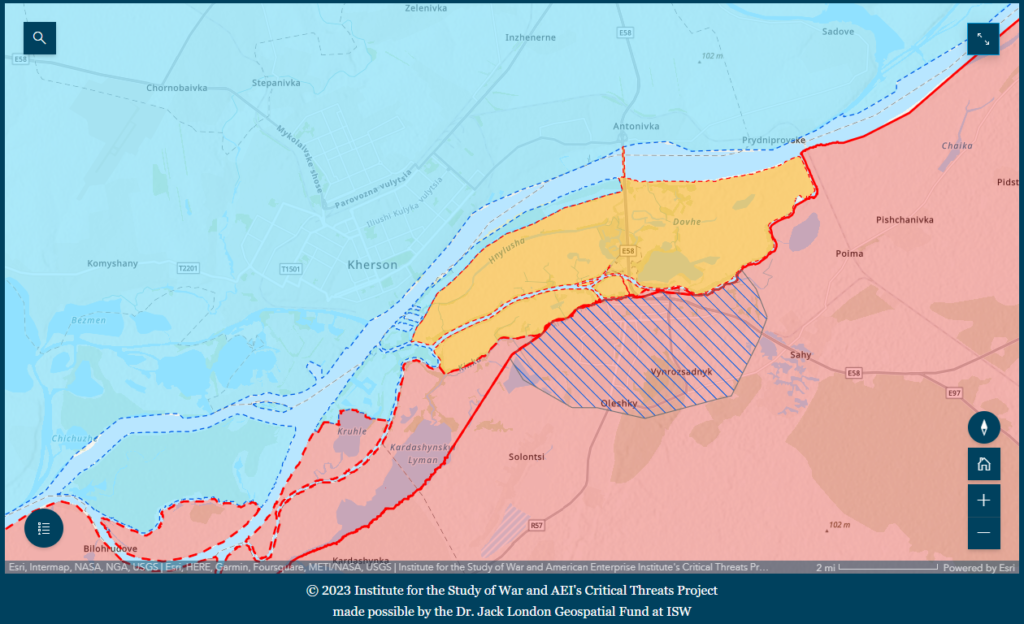

SILVER SPRING—Hardly an institution to prematurely declare changes on the ground in Ukraine based on specious information, the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) on April 22 noted, having consulted various corroborating sources, that Ukraine had established “positions” across the Dnipro River (or Dnieper) from the Kherson City area on the bank of the river east and south of the city after months of a static front, with one of ISW’s lead analysts—George Barros—posting a map the next day showing several positions on that side of the river controlled by Ukraine. In its typically responsibly cautious style, ISW was careful not to call the “positions” a “bridgehead” in a subsequent post, but, rather, “an enduring presence.”

In the two weeks since, while the longer sliver of penetration has pulled back to close to the river, Ukraine has expanded its presence on the other side of the river in a far wider band running west along the entirety of the part of the south/east bank of the Dnipro across from Kherson City. Russia has shown zero offensive capability in this region for months, and Ukraine’s presence on this bank over the past two weeks will continue to grow with a Russia incapable of marshalling resources to mount an offensive here unless it cannibalizes forces from elsewhere to disastrous effect, and, since most of Russia’s forces constituting “elsewhere” are in the east, and given that ICC-arrest-warrant-winning Russian President Vladimir Putin has resoundingly prioritized the eastern theater, that is not going to happen.

Indeed, building on this point, it is clear that with Putin’s manic, obsessive focus on Bakhmut that there has not been any significant Russian ground offensive activity anywhere outside of Ukraine’s east for many months because Russia simply has not had that kind of offensive capability elsewhere because of this focus, and control maps make this reality painfully obvious.

Note that I did not write successful offensive capability, just offensive capability, as even that capability in the east has been pitiful and Pyrrhic in the extreme, with progress coming at a snail’s pace if at all, mostly in or near Bakhmut. As I have noted before, these Pyrrhic advances coming at a terrible cost in lives and resources have done more to open Russia to counterattack than to cement any lasting major strategic gains for Russia. And with the panicked public theatrics between Wagner mercenary tin god Yevgeniy Prigozhin, Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov, and the hapless Russian military leadership, it is clear the Russians seem to have finally realized this and are flailing to try to meet this looming threat. All are de facto or de jure supposedly part of a unified military in theory, but in practice, all are a doing a fine job demonstrating the dire dysfunction of the Russian military that is the product of two decades of Kremlin policy under the firm if incompetent military hand of Putin.

In the southern central theater, since Ukraine recaptured the north/west bank of the Dnipro in Kherson Oblast from Russia in the first half of November, Russia has not even really tried to retake anything on that side of the river. At the time, it was noted that many of the surviving Russian troops that were withdrawing from there were in a sorry, beat-up, poorly-supplied state, and the bulk of Russia’s resourcing since then has been directed towards Bakhmut. While Russian troops are clearly digging in on the south/east bank of the Dnipro, Russia’s best troops and equipment should not be expected to be among them given Russia’s focus on Ukraine’s east and the horrific casualties it has sustained.

Furthermore, as Russia is now spread thin throughout Ukraine after taking these grievous losses and still persists in mostly futile offensive activity in the east, it cannot be expected to be offering much in terms of defense in depth, as fortifications need actual troops to man them and, in one example, satellite images from February progressing through late April show a major Russian military hub in Crimea having nearly emptied itself of troops and supplies.

On that south/east bank of the Dnipro, Ukrainian troops are, as usual, using their huge advantage in precision ranged weaponry to hit Russian logistics targets in the area and beyond, deep into Crimea and Melitopol in neighboring Zaporizhzhia Oblast, softening up the overall Russian positions to pave the way for an eventual assault, just like they did before they pushed Russia out of the north/west Bank of the Dnipro back in November. It is also crucial to note that the Dnipro is the last major natural barrier between Ukrainian troops and Crimea, as, with their new positions across the Dnipro, Ukrainian troops are now just some sixty miles (as the crow flies) of flat, difficult-to-defend coastal plain from Crimea’s northern border…

Relatedly, retired American Gen. Mark Hertling has repeatedly noted that Ukraine has to move troops and supplies around much shorter interior lines as opposed to Russia, which has to do the same over far longer exterior lines, making the task far easier for Ukraine and far harder for Russia. That means, in the coming counteroffensive phase, it will be relatively easy for Ukraine to move troops and their supplies quickly to surprise Russia and keep it off-balance even as Russia will struggle to reinforce or redeploy, and Russia’s far longer transit routes leave its columns vulnerable to Ukraine’s HIMARS, M777s, Caesars, and other precision weaponry that Russia lacks.

Russia now has a conundrum pretty much exactly the same as one I have discussed earlier that it suffered from this past summer and fall: Russia only has bad choices, and whatever adjustments it makes are going to come at dear cost. After all, Russia is not performing well on the battlefield anywhere, for, as noted, its ground assaults are either only making gains that come at staggering costs in just a minute number of areas or are completely failing. This means that if Russia moves troops from or diverts reinforcements going to one area in order to reinforce anywhere else (in this case, its remaining positions in Kherson Oblast), it will leave itself weaker and more vulnerable at that first front. But if it does not do this, it will hurt its odds at mitigating whatever is coming at it from Kherson, which Ukraine can time based on what Russia is and is not doing as far as redeployments and reinforcing. All the while, Ukraine could also easily be preparing an (additional?) onslaught where Russia is not anticipating one, as happened in the Kharkiv area late last summer while Russia was expecting the hammer-blow at the time to come for Kherson City, which still came anyway after devastating Russian losses in men, equipment, and territory from Ukraine’s Kharkiv-front counteroffensive.

As I have pointed out regarding previous counteroffensives, it comes down to simple math: Russia’s numbers are weak on both sides of the equation and it is basically left to choosing how badly, how quickly, and where to lose in shuffling resources from one location to another. For, as I have argued previously, the rest of the variables in the equation are also bad for Russia and increasingly inferior to those of Ukraine’s qualitatively superior forces, especially morale, training, weapons, logistics, decreasing vs. increasing capabilities, how they have been performing over time as well as recently, and leadership.

I noted late last year that this war had long ago settled into two alternating phases: Ukrainian counteroffensives and the preparation of them. Whether this is the end of the latter or the beginning of the former still remains to be seen, but that does not change the momentous nature of Ukraine’s crossing of the Dnipro as well as Russia’s failure still to fully take Bakhmut, as the Prigozhin/Kremlin public squabbling emphasizes for the latter. What Ukraine does and when on the south/east bank of the Dnipro—and how Russia reacts to that—will likely have ramifications throughout Ukraine, in Bakhmut and beyond, just as Bakhmut’s campaign has been having ramifications far beyond its local theater as Russia nonsensically hemorrhages men and supplies there to the detriment of its efforts everywhere else in Ukraine. Ukraine seems to understand how to synergize its operations across various fronts and sectors, while Russia does not, no small part of the equation that has Ukraine winning and Russia losing this terrible war.

What is clear is that Ukraine establishing itself on the east/south bank of the Dnipro across from Kherson city potentially puts the rest of Kherson Oblast as well as Zaporizhzhia Oblast and the Crimean Peninsula into play in the near future. The Russian-occupied parts of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, like the parts of Kherson Oblast Russia still occupies, are mostly hard-to-defend flat coastal plains, and as the last oblast between Ukrainian forces in the south and Donetsk Oblast in the east where the heaviest fighting has been taking place, Zaporizhzhia is the last obstacle Ukraine would need to overtake before its forces in the south could link up with its forces fighting fiercely in the east (including Bakhmut). In turn, that may allow Ukraine to outflank and overwhelm Russian positions in the east throughout the Donbas and all the way to the Russian border. Thus, these developments on the Dnipro River and Bakhmut and their consequences may snowball into other key parts of Russian-occupied Ukraine sooner rather than later in ways that can alter the strategic and tactical caluculi of the entire war.

Brian’s Ukraine analysis has been praised by: Mykhailo Podolyak, a top advisor to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky; the Ukraine Territorial Defense Forces; Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, U.S. Army (Ret.), former commanding general, U.S. Army Europe; Scott Shane, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist formerly of The New York Times & Baltimore Sun (and featured in HBO’s The Wire, playing himself); Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL), one of the only Republicans to stand up to Trump and member of the January 6th Committee; and Orwell Prize-winning journalist Jenni Russell, among others.

© 2023 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see Brian’s eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here).

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed one million content views on January 1, 2023. Real Context News produces commissioned content for clients upon request at its discretion.

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!