Why the way forward for biofedense merits a Cabinet addition and how that Department should look and operate

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981, YouTube) August 27, 2020

Author’s note: I wrote most of this in April and May, originally as part of my much longer coronavirus deep-dive, but held off on publishing this part in the hopes that I could publish it with a major outlet, making some edits and additions in the meantime, but I do not want to wait any longer. So, if you find value in my policy proposal here, please do share profusely!

Winter Is Coming.

—House words of House Stark, in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones (1996)

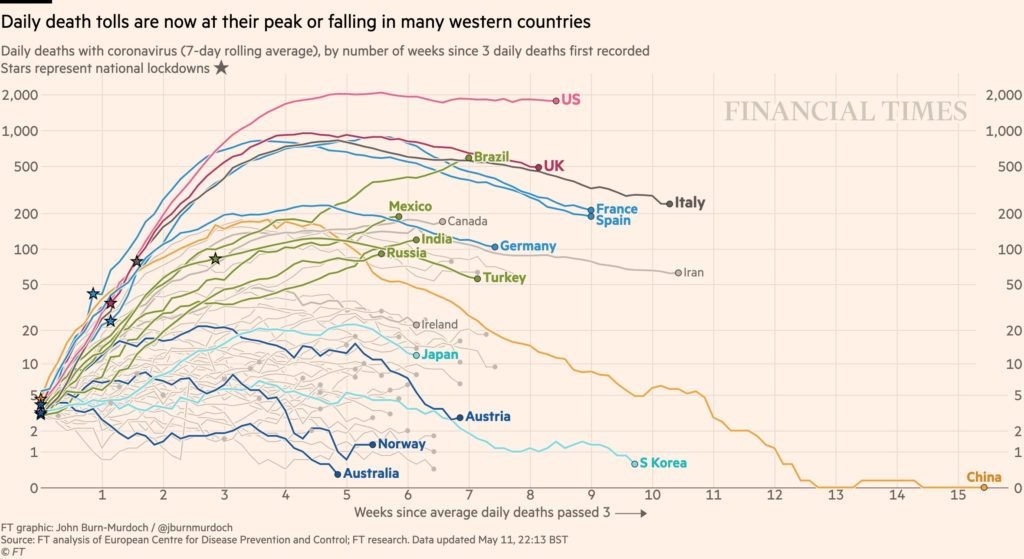

SILVER SPRING—These past few months, the United States has more and more resembled a failed state (to borrow George Packer’s phrase and Anne Applebaum’s sentiments as expressed in The Atlantic) in various ways to varying degrees as it has produced one of the least effective coronavirus pandemic responses of any nation on earth, as the below chart makes clear:

I have discussed that chart in my late-May deep-dive, big-picture exploration of the coronavirus/COVID-19 pandemic and its implications, one in which I also pointed out both that the coronavirus pandemic poses a number of dire threats that we are simply ill-suited to handle and that this is the situation, in part due to our overall structural, societal, even cultural inability to effectively confront unconventional and asymmetric threats for much of our history.

Yet as Modern War Institute (MWI) nonresident fellow Max Brooks noted in a Foreign Policy piece, we are not helpless against the threats presented by coronavirus. These threats do not have to mean our defeat, which “the world can stop… And nobody has to develop a whole new weapons system to do it. Unlike all other means of war, where new inventions require counterinventions for protection, from bulletproof vests to anti-tank missiles, all we have to do is change our thinking. All we have to do is see public health as national security” and “strengthen…cooperation with global health networks.”

Along these lines, in a mid-April webcast conversation with Sen. Bernie Sanders, former Vice President Joe Biden said “I really think we should be thinking about having a new office, a new Cabinet office, on pandemics in the United States,” and this is what I had been thinking, too, in preceding months while I had been working on this piece and my earlier coronavirus work.

Before the next big biothreat hits us—be it a natural pandemic or one resulting from biowarfare or bioterrorism—I propose the creation of a presidential-Cabinet-level Department of Pandemic Preparedness and Response (DPPR), with its Secretary a top-tier official on the National Security Council (NSC) appointed to a ten-year term much like the FBI director to ensure a higher degree of continuity, signal the position’s non-partisan nature, and keep the department less exposed to political ups-and-downs. If 9/11 saw the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as a major part of our national response, this far deadlier coronavirus pandemic can see the creation of DPPR as a response.

DPPR would be a civilian-led joint civilian-military agency, designed to coordinate a national civilian and military response in the event of a pandemic, something of a mini-Pentagon for pandemics but with a higher proportion of medical and logistics experts than anything else but also with strong legal components to navigate the various local, state, and federal legal structures a pandemic would touch, one that would work closely with the Department of Justice (DOJ) and other agencies but still remain independent.

I. The Army Pandemic Corps

Involving the military is essential. For one thing, because of distinct and clear resourcing, cultural, and structural reasons, the military has a high level of discipline and efficiency relative to civilian agencies, is able to move large numbers of people and equipment with more ease, and can act more swiftly overall. In contrast, civilian planners and capacities have failed and are still failing spectacularly during this coronavirus pandemic, and a huge portion of America’s coronavirus response has come down to an ad hoc approach, only adding to the confusion and chaos. As Gen. Russel Honoré (who helped lead America’s response in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina) explained about our current pandemic, the main choices for logistics are between the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA, a civilian agency under the Department of Homeland Security, or DHS) and the military. But, as he also explained, FEMA is designed to handle one or several localized emergencies at once, not a full-fledged national one; it simply does not have the capacity to run as the point organization for this pandemic. Instead of needing to create an entirely new civilian apparatus that can handle a national pandemic or slapping together disparate agencies not used to working closely together, building upon existing military structures that already have far more capacity than any civilian apparatus makes much more sense. And, as will be demonstrated below, there are so many other ways that a large military role further enhances both preparedness and response for pandemics. And yet, the military in its current state would have a tough time taking over pandemic operations, navigating unfamiliar state and local legal jurisdictions. Expanding the military with a new Army Pandemic Corps, as described below, will address these issues and put DPPR, including the Corps, in a position to be the best possible entity to handle pandemic preparedness and response.

The DPPR’s main logistical deputy would be a new four-star Army general officer, officially a liaison reporting primarily to the Secretary of Defense as part of the Army and the Department of Defense (DOD) in non-pandemic times and but whose main deference and primary reporting line would switch to the Secretary of DPPR in pandemic times. This logistics-specialized general would command a single new Army corps of pandemic response professionals—military personnel who specialize in logistics, transport, maintenance, medicine, and protective gear—that would be formally commanded by this four-star general as part of the Army and Pentagon command structure during non-pandemic times, during which it would focus on preparation and training. But when a pandemic is upon us, the corps would be handed along with its four-star general to the command of the DPPR secretary as a temporarily-formal part of that agency. Keeping the corps under the same four-star general but switching his position from the Pentagon pre-pandemic to the DPPR to deal with a pandemic ensures a proper balance between continuity and flexibility, both of which have been lacking in our current pandemic leadership. The switch would be relatively smooth, too, since both the commander and the Corps itself will have spent much of the non-pandemic time liaising with all the relevant actors. This general would need to be approved by both the Defense and DPPR secretaries and would clearly understand his dual roles, specifically when one supersedes the other.

A large portion of the Corps who would be full-time active-duty military and those who would be reservists would not be allowed to have civilian roles as first-responders or needed medical staff elsewhere (as many in the military currently do), thus avoiding the issues of a callup cannibalizing crucial local response staff as would be the case with call-ups of the National Guard, a problem discussed by Mississippi National Guard Maj. Dennis Bittle in an MWI piece. The U.S. already has a shortage of doctors and nurses, having to import many from foreign countries. This Army Pandemic Corps could provide generous incentives to make its positions attractive—including paying for the college and advanced degrees of those who want to bindingly commit to serving in the Corps for a certain number of years—thereby serving as an incubator for increasing our overall civilian healthcare workforce, allowing those who eventually leave the Corps to fill important roles in the U.S. healthcare system. When coronavirus subsides, the new normal will require far more healthcare workers and this Corps is an excellent way to facilitate this growth.

During non-pandemic times, Corps soldiers can supplement existing civilian and non-Corps military teams in emergencies in ways that do not lead to dependence or hamper their ability to be rapidly deployed for a pandemic. And those with enough experience can help train relevant local and state personnel, too. Teams of the Corps can also shadow other healthcare workers as well as relevant workers in other fields both in the U.S. and abroad to learn even more. They can also significantly supplement U.S. foreign aid and assistance to organizations like the United Nations (including the WHO), NATO, and the African Union. Such work will not only build goodwill among allies and friends, it will also help forge new relationships, improve America’s image abroad, and help America to gain valuable experience from medical and logistical situations that our personnel would not otherwise gain. Such an approach was taken by the Obama Administration in sending teams from the Army and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)—a main agency of the Department of Health and Human Services, (HHS)—to West Africa to assist with fighting a major Ebola outbreak there, a rapid, proactive response that helped to prevent a much larger outbreak even as the deadly disease still ended up spreading to ten countries on three continents.

As Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky remarked in a mid-May op-ed extolling the value of international cooperation in the coronavirus era, “in early April, we sent some of our doctors to Italy. Their work treating patients there has helped us to learn lessons about the spread of the disease that are now informing our own quarantine procedures and in turn, helping to save lives here.” Just imagine if we had had thousands of members of the Corps ready to deploy in northern Italy when Lombardy was put on lockdown on March 8: not only could we have saved lives there, we would have learned valuable firsthand lessons and deepened our experience with COVID-19 before it slammed the U.S., saving American lives, too. As it actually played out, Italy had to request assistance from the U.S. rather than the U.S. taking a leading, proactive role.

From such cooperation and experiences at home and abroad, members of the Corps can amass and pass on institutional knowledge that will enhance local, state, national, and international bodies of knowledge. The Corps can play a leading global role in research, evaluation, and dissemination of findings as well as in running simulations with a variety of actors. Medical “wargames” should be a major priority along with military wargames, and few institutions would be as well-suited for this as America’s new Army Pandemic Corps.

The Corps would also greatly facilitate civil-military cooperation. In non-pandemic times, the Corps could take input from various relevant bodies at all levels as part of the Army with the Army understanding that the Corp’s mission under Army control is primarily one of learning, bridging, and supplementation. In times of military pressure, this ensures we have a significant boost to military medical and logistical operations, but, as in the Corps’s supplementary civilian-support operations, without creating dependency so that rapid deployment for pandemic operations is still possible without compromising normal military operations.

Writing for the U.S. Naval Institute, Commander of NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command Naples, Italy, U.S. Adm. James Foggo—who has been dealing with COVD-19 in Italy—calls germs the seventh domain of warfare. In his piece, he notes that “logistics are the sixth domain of warfare, the Achilles heel of any military force. When fighting pandemics, the logistical capabilities of the force are paramount.” He also notes that “confronting a pandemic requires an all-hands approach—we must work with our interagency and host-nation partners to leverage mutual strengths to stem the spread of the virus, while offering our support to those in need. Yet we must be mindful of our operational readiness, retaining the ability to respond immediately if challenged in another domain of warfare.” Some of his top takeaways from his experience as a commander in Italy facing coronavirus are that, to better face biothreats (including pandemics), we must protect our forces, ensure continuity of operations, build and preserve strong relationships with allies and partners, elevate experts, fuse with the other domains of warfare, prioritize humanitarian intervention early, and train and wargame for biothreats intensely and often. The Army Pandemic Corps, as I have proposed it, would specifically and significantly advance all these priorities and more.

And yet, as Dr. Jacob Stoil and Army Maj. Bethany Landeck point out in an additional MWI article, it has been decades since the U.S. military included large-scale epidemic response in its operations, as was the case in major wars of the past. Looking at the current state of the military in yet another MWI piece titled “The Military Is Not the Nation’s Emergency Room Doctor,” U.S. Air Force Center for Strategic Deterrence Studies Director Al Mauroni noted the military should be ready to support civilian efforts in a pandemic, but not to take them over. The Corps will restore and elevate the past role discussed in the former and keep things in the spirit of the latter by keeping the military in a support role and civilians in the top leadership roles. The Corps will also very much help advance needed reform within the military by addressing problems that the pandemic has exposed, shortcomings highlighted by Army Reserve Capt. James Long in still another MWI piece discussing “our lack of preparation, in the form of adaptive digital networks and robust connective tissue with civilian partners.” While the civilian apparatuses have in many ways failed us during this pandemic and the military did not have a clear, robust role to play when it could have made a clear, robust difference, DPPR with a new Army Pandemic Corps at its heart addresses both of these crucial gaps.

II. CDC and FEMA Reorganization

The head of the CDC would simultaneously occupy a deputy secretary position within the DPPR that would function as the main liaison between HHS/CDC and DPPR, but in times of pandemics would, along with the CDC itself, report primarily to DPPR, switching formally from HHS to DPPR much like the general and his Pandemic Corps. This would ensure that HHS and DPPR have strong coordination both before and during a pandemic and give the appropriate command and departmental emphasis when necessary. DPPR would also have its own infectious disease intelligence desk, to coordinate with staff at the Defense Intelligence Agency’s National Center for Medical Intelligence (a small portion of whom would be transferred to DPPR’s desk upon its creation to jumpstart it), American medical infectious disease teams, the WHO, and global experts to track and identify pandemic threats. In short, the CDC’s pandemic-related work would carry on as normal but with a boost and different reporting lines during a pandemic.

DDPR would also have lead jurisdiction when it came to related the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA, normally under DHS) operations for the duration of the pandemic. However, unlike the CDC and Pandemic Corps, all of FEMA would not be part of the switch. Like his CDC and Pandemic Corps counterparts, the FEMA Administrator would during non-pandemic times have a dual liaising role as a deputy secretary of DPPR, but he would stay reporting to DHS both then and during a pandemic. The Secretary of DPPR during a pandemic would automatically be authorized to take all FEMA personnel working on pandemic operations, automatically being able to allocate a certain portion of all FEMA field personnel and the support staff for those field teams directly to his DPPR, with them reporting directly to his office. Beyond that specified portion, if the DPPR secretary feels he will need more FEMA resources, that can be worked out by reaching agreement with the head of FEMA or, failing that, the president would mediate and decide. This ensures that FEMA would have considerable capacity to deal with non-pandemic emergencies even during a pandemic, allowing flexibility and for staffing levels be based on the bigger picture, while still empowering DPPR to lead on pandemic matters.

III. Keeping DPPR from Being Politicized in a Hyperpartisan Era

U.S. Army Reserve Maj. Wonny Kim notes for MWI the failure of communications tactics and strategy, and, without a doubt, politicization of public statements on the pandemic at the highest levels of government—up to and including dangerous disinformation and misinformation on vital health information (and on things as simple as wearing a mask and social distancing)—is a regular feature of this failure in communication. Thus, in order to prevent politicization of information related to pandemics and preparedness, DPPR must regularly brief—in times of pandemics and in non-pandemic times—not only the White House, but all major intelligence agency heads, top Cabinet officials, as well as top relevant leadership of both parties in Congress, including of key committees, at regular intervals. All governors of U.S. States and Territories and their attorneys general would also be briefed along with all nine Supreme Court Justices, the latter in case there would be legal challenges between the Executive and Legislative Branches over DPPR information dissemination, giving the Supreme Court the context to rule quickly on those disputes. All non-sensitive information will be made publicly available and the DPPR secretary will also brief the media regularly. If certain information is felt by the White House—specifically the president and a majority of the Principals Committee of the NSC—to need to be kept from the public and maintained as secret because of issues of national security and/or protecting intelligence gathering assets and methods, the highest congressional leadership from both parties must also be briefed in full on these issues of secrecy along with the nine Supreme Court Justices to, as stated before, provide the justices proper context should disputes arise. Such disputes can be initiated by congressional leaders—the top leader of either party in either the House or Senate would be enough to trigger a formal challenge—and the Supreme Court would exclusively handle and fast-track these disputes to avoid delays during a pandemic. In short, all three branches have potential major roles in deciding what information is kept from the public and lawmakers overall, helping to keep information from being used or withheld for partisan political purposes.

IV. DPPR: Improving Preparedness and Response at All Levels, Minimizing Politics

At the state and local levels, we have seen vast gulfs in competency from one state to another and within the federal government during this coronavirus response. By having DPPR preplan and coordinate with Congress, other parts of the federal government, and with states and localities before the next pandemic, our entire society will better prepared. This way, DPPR insulates the nation from poor leadership at multiple governmental levels. Relieving governors and mayors of the need to do as much planning as we have seen them have to scramble do on their own (see Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan’s twenty-two-day odyssey to get coronavirus tests from South Korea and keep them from being confiscated by the Trump Administration) in favor of knowing they can tap into plans, logistics networks, and coordination already well-laid out in advance will then free up local leaders and resources to focus on aspects of disaster management more uniquely suited to their unique capabilities (e.g., supporting local officials, assuring the public), meaning the overall response on the levels most felt by actual citizens will be that much more effective. And local staff will be better trained and prepared since DPPR personnel will be dedicated liaisons and trainers in non-pandemic times, with those relationships developed from all the DPPR’s non-pandemic period activities paying massive dividends on multiple levels.

Conclusion: A Bold, New Cabinet Department and a Bold Reorganization for an Existential Threat

In the end, DPPR represents what is ideal in times of dire threat: vast, temporarily, and transparently concentrated power allocated in a preplanned way with all relevant actors understanding their roles and responsibilities and having been included in the preplanning. Ad hoc responses can be great, but they depend greatly on the quality of individual leaders and can fail just as often. Leadership will always matter, but setting up the DPPR in the manner described above will not only limit the damage poor leadership can do by providing a clear institutional framework that can relieve top leadership of the need to be involved in so many details, it will allow top leaders to focus on calming the people of the nation, international coordination and outreach to other heads of state and major international bodies, and recovery and post-recovery planning while the actual day-to-day disaster management and logistics are left to the professionals best suited to handle them, operations we are seeing have been currently neglected and mismanaged at the top federal levels to disastrous effect. Instead of arguing and debating different agency plans and different ideas and philosophies for crucial lower-level wonky decisions, instead of having to introduce personnel to each other and form working groups or task forces in an ad hoc manner, which, in this case, has produced confusion more than anything else and failed to deliver adequate results, we can have a clear, singular road map for general operations and overall approaches, a road map that minimizes infighting, confusion, uncertainty, and dependence on individual political leaders’ competence.

While there is certainly possibility for confusion and head-butting with this more complex structure and roles for the Army Pandemic Corps, the CDC, and FEMA, with proper leadership, better coordination and more effective, robust operations should result, especially compared to the current ad hoc, dysfunctional coronavirus response. Even allowing for new potential issues, the net effect is of these overlapping relationships is still very likely to be forcing a greater level cooperation and coordination than currently exists, as DPPR and especially the Pentagon, CDC, and FEMA—but also HHS, DHS, and DOJ—would need to be intimate partners in planning and executing policy. In essence, just as DHS became an umbrella agency that involved a reorganization of many agencies after 9/11, DPPR would function both as a permanent planning and coordination agency and specialized, temporary DHS for pandemics to be activated with a higher level of authority and responsibility, from planning and coordination in one state to execution in another. If this sound superfluous, consider that the United Nations has a whole major office within its Secretariat—the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)—that focuses on running complex humanitarian efforts and maintains many relationships before and after such efforts rather than allow for an ad-hoc response for each humanitarian disaster.

In fact, history shows there is no major reason to ipso facto oppose complex or joint civil and military overlap or commands. Going back to the ancient Roman Republic, one could argue that one of the main reasons Rome’s (surprisingly) democratic republic—upon which the American Founding Fathers based our own republic—was able to govern its expanding empire so successfully for so long before the rise of the autocratic emperors was its ability to both divide and expand creatively both the wielding and implementation of executive authority (imperium) within its flexible yet strong constitutional framework, especially in its combination of civil and military authority abroad in ways that helped avoid conflict between the two without overwhelming any one officer-holder or office. Here we would think less of the of rarely utilized office of dictator for the most extreme of emergencies, which essentially suspended the normal constitutional order and invested overwhelming power in one man, and more of the special office of proconsul (pro consule), a special version of the authority of the annually elected top normal office-holders (a pair of consuls, on which the American presidency is based). Proconsuls could still be given extraordinary powers but over a limited sphere of affairs and for a limited time. Thus far avoiding the eventual giant excesses of imperium that helped bring down ancient Rome’s republic, America has attempted something in this Roman tradition on notable occasions. At the dawn of the twentieth century, we have (then-future President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) William Howard Taft as a civilian governor being given proconsularesque authority by President William McKinley over U.S. civil and military authorities in the newly acquired Philippines after the Spanish-American War. Yet a certain vagueness, political disputes, McKinley’s assassination, his successor Theodore Roosevelt’s reluctance to be involved, and U.S. military commanders’ resistance to civil control of the military outside the president exercising it himself (and even then…) meant the actual application of this idea was limited, but when it was, the largely benevolent Taft mostly improved the situation in the Philippines in spite of military leaders’ sometimes-tendency to make things worse with harsh overzealousness there. Other notable American pronconsular moments include Reconstruction after the Civil War and Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Japan after World War II, but there are numerous examples of American variations on the Roman proconsular model over many years up through our recent overseas wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and even Gen. Honoré in New Orleans after Katrina (plus, America is hardly alone in utilizing this model). Examples of different types of American civil-military overlaps involve the U.S. Army’s Civil Affairs branch (including its soldiers serving as advisors for United Nations and NATO missions) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which from some of the earliest days of United States history through the present has been and is still massively engaged in civilian projects affecting large portions of the American population.

So the idea of temporarily having a military corps under civilian control should not be thought of as too revolutionary: after all, all American military forces serve under the civilian U.S. President, civilian Secretary of Defense, and some other combination of civilian (deputy) secretaries overseeing the various branches of the armed forces, a principle of civilian control enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Also enshrined in the document is the idea of temporary measures to meet extraordinary challenges, such as the suspension of habeas corpus in Article I Section 9, and plenty of modern-era laws have allowed for temporary unorthodox measures, from the 1950 Defense Production Act to far more typical presidential– and state-level disaster declarations, which have seen unprecedented application during this coronavirus pandemic but which are already largely being lifted (though the lifting seems frighteningly premature).

But moving in this general direction of more concentrated civilian authority over biodefense is what some of the most notable experts have already articulated. A major working group meeting on biodefense that convened in 2014-2015—one that involved many senior former and current government officials from both major political parties as well as numerous experts in various fields—produced a landmark report late in 2015, A National Blueprint for Biodefense: Leadership and Major Reform Needed to Optimize Efforts, and among its top recommendations was to institutionalize, centralize, and prioritize biodefense at the very highest levels of government. The creation of DPPR as a Cabinet-level agency does just that.

While DPPR’s creation along the lines described would certainly be a shakeup of the existing order and way of doing things, as Army Lt. Col. ML Cavanaugh notes in his MWI piece on coronavirus-era military strategy:

Organizations are loath to try new things, take on new projects, and risk new avenues of approach. Only when real-world crises confront us do we really and ruthlessly set priorities and change our behavior accordingly. This is rare. Very rare.

COVID-19 is already permitting ideas to go forth that might have seemed absurd just months ago. This is how the unthinkable gives birth to the impossible.

King Abdullah II of Jordan expressed similar sentiment in a late-April op-ed, that

the moments of unity inspired by [major global] events—and the financial crises and natural disasters we’ve also faced over the years—have never lasted long enough to push us to fundamentally rethink the systems we have in place. More often than not, our responses have done little more than plug holes, falling far short of what could be achieved with modern technology.

…Many are optimistic we will simply rebuild after this pandemic. But rebuilding is not enough. We should focus instead on creating something new, something better.

…That means recalibrating our world and its systems.

He could not be more right. And since his government in Jordan has swiftly enacted far more successful and competent national coronavirus measures than we did (and far earlier)—including robust targeted and random testing—perhaps we should heed his advice even more so.

In the end, we can and should be better prepared for the next pandemic, and there will be one. Whether or not we will adapt, there is a good chance our enemies will, with the COVID-19 devastation serving as a kind of inspiration we wish did not exist, nor occur to the human mind. Let our minds take truly inspiring direction from this crisis, inspiration that accepts major and creative top-level reform as urgent and necessary.

Whether coming from nature herself, a foreign enemy government, or terrorists, the next bioassault as powerful as or even worse than the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic will take a nontraditional, unconventional reform of our national biodefense structures and approaches in order for us to be properly prepared to face it. This Cabinet-level Department of Pandemic Preparedness and Response exponentially improves the odds that we will be, regardless of who is in the White House.

© 2020 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see Brian’s latest eBook,Coronavirus the Revealer: How the Coronavirus Pandemic Exposes America As Unprepared for Biowarfare & Bioterrorism, Highlighting Traditional U.S. Weakness in Unconventional, Asymmetric Warfare, available in Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, and EPUB editions.

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here and, of course, please share the hell out of this article!!

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!