Why a siege is far preferable to an assault (for now) and how that can be set up

(Russian/Русский перевод; Если вы состоите в российской армии и хотите сдаться Украине, звоните по этим номерам: +38 066 580 34 98 или +38 093 119 29 84; инструкции по сдаче здесь)

By Brian E. Frydenborg (Twitter @bfry1981, Threads @bfchugginalong, LinkedIn, Facebook, Substack with exclusive informal content) June 13, 2023; *UPDATE June 22: Ukraine has hit the Chongar Strait bridges near Chonhar village and also the rail bridge nearby, as I predicted!; see related April 24, 2022, article How Ukraine Can Take Back Crimea from Putin’s Reeling Russian Military; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed one million content views on January 1, 2023, but I still need your help, please keep sharing my work and consider also donating! Real Context News produces commissioned content for clients upon request at its discretion. Also, Brian is running for U.S. Senate for Maryland and you can learn about his campaign here.

“Ah, advisers, advisers!” he said. “If we’d listened to everybody there in Turkey, we wouldn’t have made peace and brought the war to an end. Everything quickly, but quick turns out to be slow. If Kamensky hadn’t died, he’d have been lost. He stormed fortresses with thirty thousand men. It’s not hard to take a fortress, it’s hard to win a campaign. And for that there’s no need to storm and attack, there’s need for patience and time. Kamensky sent soldiers to Rushchuk, but I, with just those two (patience and time), took more fortresses than Kamensky and made the Turks eat horseflesh.” He shook his head. “And the French will, too! Take my word for it,” Kutuzov said, becoming animated and beating his chest, “they’ll eat horseflesh for me!”

—Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, Volume III, Part Two, XVI, 1869

SILVER SPRING and WASHINGTON—Some rules of war are virtually ironclad. Among these are the ideas that flanking is preferable to a full-frontal assault, morale and training increase value per soldier, defending high ground bestows a significant advantage while attacking it does the opposite, numbers alone cannot guarantee victory, you can win a battle but still lose the war, and von Clausewitz’s famous maxim that “War is merely the continuation of policy [or politics] by other means,” among others.

I.) Why

The idea I am most interested in here, though, is that in most situations, the preferable option for a commander is to preserve as many of his own troops’ lives as possible while still advancing towards achieving overall goals. In certain situations, that means sacrificing an enormous number of troops still, such as defending a capital city or a major supply hub without which an army cannot feed or equip itself. But especially on offense, a commander has more and usually better options than this; on offense, a commander can far more often engage in times and places of his choosing for priorities of his choosing.

When it comes to Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, there are many who rightly so regard Crimea as of the utmost importance to Russia. It is the part of Ukraine Russian President Vladimir Putin prioritized conquering before any other, which he succeeded in doing so in early 2014, and it is the only distinct part of Ukraine that he has held onto in its entirety from that point though the current far-escalated phase of the war, which was inaugurated by Russia on February 24 of 2022. One could even call it the spiritual heart of Putin’s westward imperial ambitions for Europe, but the importance also has deeply practical aspects, too: the peninsula hosts the main base for the Russian Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol, the one warm-water port in Russia’s possession that is actually contiguous to Russia (as opposed to Syria’s Tartus, where Russia has established a naval base while supporting that nation’s mass-murdering dictator, Bashar al-Assad). Russia has also invested much economically into Crimea, not least of which was Putin’s rushed-but-still-historic Crimean Bridge–also known as the Kerch Strait Bridge—connecting Russia to Crimea and more-or-less completed in 2018 (2019 for the rail part) with much fanfare, opened by Putin himself and currently the longest bridge in Europe. Russia has also moved hundreds of thousands of its citizens into Crimea since its illegal invasion and annexation and it was one of the most popular vacation destinations for Russians (until Ukrainian missiles, drones, and special operations forces conducted successful strikes deep into Crimea; yet decades and centuries earlier, many a tsar or top Soviet official maintained dachas there to enjoy the warm weather and the beaches). And it has been a major logistical hub and transit route for military forces supporting Russia’s military occupation and war effort.

Because of this, there is a set of commentary calling for Ukraine to liberate Crimea as soon as possible.

Yet this thinking falls for a more unnecessary symbolic approach when there is a far more practical approach available.

This different approach would have Ukraine take Crimea off the table for Russia as far as any practical military use for wider support of Russia’s military operations elsewhere in Ukraine and the Black Sea while allowing Ukraine to prioritize troops for where they are most needed.

In this approach Crimea is quickly and easily neutralized while the bulk of Ukraine’s forces in the south would roll through the Russian-occupied parts of Zaporizhzhia Oblast (i.e., province) to link up with its own hard-pressed forces in Donetsk Oblast and the rest of the Donbas-area front.

Keeping in mind the goal of keeping as many Ukrainian troop alive as practicable, it must be noted the heaviest fighting incurring the most casualties for Ukrainians has been on the Donbas line stretching through Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, thus, it would not make sense to prioritize an assault on Crimea over combining other forces with the forces in the east. Getting more Ukrainian troops to the east as fast as practicable would change the balance of power in the east and thus vastly reduce Ukrainian casualties on its Donbas front. If there were a way to quickly neutralize Crimea and to move the bulk of Ukrainian forces engaged in the south over to the east, that would help to save as many Ukrainian lives overall as possible. After all, there really is not much, if any, downside to neutralizing Crimea as a threat, setting it up for a later conquest, and pushing on to the east without taking Crimea first, as Crimea only offers resupply and reinforcement to the lands Ukraine would be cutting off Crimea from anyway were it to seal Crimea off from the north.

II.) The Geography of How

So, would Ukraine be able to neutralize Crimea as a base for Russia? Yes, for the simple and easy to understand reasons that hinge on understanding Crimea’s geography: there are only extremely limited ways to access the peninsula by land or road:

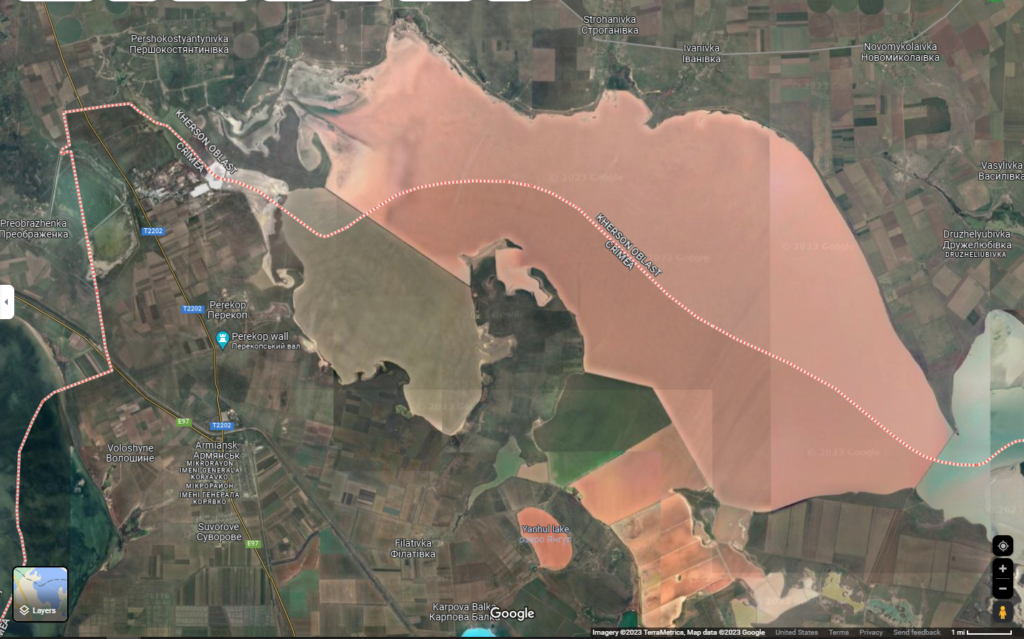

- In the west of northern Crimea, there are two major roads (those roads quickly merge into one on their way south) and a railway into the very narrow Isthmus of Perekop, Ukraine’s only natural land connection to its Crimean Peninsula and just a few miles wide at its narrowest point (the Isthmus is part of Crimea administratively). Near the northeast part of the Isthmus and administratively still in Kherson Oblast there is what appears to be a dirt path from a piece of land jutting east into the water; the path goes out into the water on what appears to be a very narrow (150 feet wide) earthen dam that cuts across the water for four miles before connecting to Crimea as part of the system of water and salinization management for the salt industry there that extracts the famous pink salt from The Sivash (the system of marshes and lagoons separating the Crimean Peninsula by water from the rest of Crimea save for the Isthmus of Perekop; more on this below). Any troop movement over this dam would be highly exposed with no cover on a very narrow path.

- Roughly a dozen or so miles to the east is what appears to be another earthen dam. The two dams keep the very pink saltwater water boxed in from west-to-east as part of the salt extraction industry. With this dam, there is a dirt path crossing 1.5 miles of water between the areas near the villages of Druzhelyubivka to the north in Kherson and Nadezhdynein to the south in Crimea; like its counterpart, this earthen dam path is also very exposed, very narrow (120 feet across), quite vulnerable, and should not be thought of a practical transit route for larger numbers of Russian troops, vehicles, and equipment.

- On the eastern side of Crimea, there is a pair of bridges side-by-side (one no longer even used) over the very narrow Chongar Strait into Crimea, by Chonhar village. The crossing is easily bottlenecked. There is also a nearby rail bridge to the west over the water that is not going to be of much use by the time Ukraine is on Chonhar’s doorstep (*UPDATE June 22: Ukraine has hit the Chongar Strait bridges near Chonhar village and also the rail bridge nearby, as I predicted!).

- East and north of the Chongar Strait, there is a bridge at Henichesk to the very long, narrow, and exposed Arabat Spit (essentially a giant sandbar that is not even fully pave-roaded), which would be impractical for moving large numbers of troops and equipment in a combat situation and could very easily be jammed up (a single brave Ukrainian defender named Vitaly Skakun blew himself up to blow the bridge early in the war, taking it out of commission for most of 2022 before the Russians repaired it: that’s the impact just one defender had). Ukraine has already recently repeatedly demonstrated the ability to hit that area with ease, including Russian military facilities in both Henichesk and on the Arabat Split just in the past few days. This Henichesk bridge is technically well inside Kherson Oblast as much of the northern part of the spit is administratively in that oblast, but it is still one of the only available ways into Crimea from the north. This is almost certainly why Russia has invested in repairing the bridge at Henichesk and expanding a paved road down the spit.

- Far further to the east and south, there is the much publicized Kerch Strait/Crimean Bridge, going from Russia into Crimea, the vulnerability of which I have discussed before and which the Ukrainians have already famously demonstrated this past October. They will likely be looking to hit the bridge again, and it has recently apparently started showing literal cracks even after repairs in response to the Ukrainian attack (it was actually a rush job by the Russians, another point suggesting its ripeness as a target).

- Apart from the Isthmus of Perekop, the rest of the space on Crimea’s northern border is the somewhat toxic set of aforementioned lakes known as The Sivash (or Syvash), which can be forded in some places, especially in the winter if the water freezes over, but such crossings would occur through water or on ice and would leave Russian units terribly exposed and vulnerable to heavy casualties from Ukrainian attacks, with Russian troops and vehicles either stuck moving slowly in marshes and lagoons or on ice that could easily be destroyed by Ukrainian forces, sucking Russian troops into ice-cold water. Let us just admit that the idea of any kind of competent Russian amphibious assault at this point in the war with what we have seen thus far is laughable.

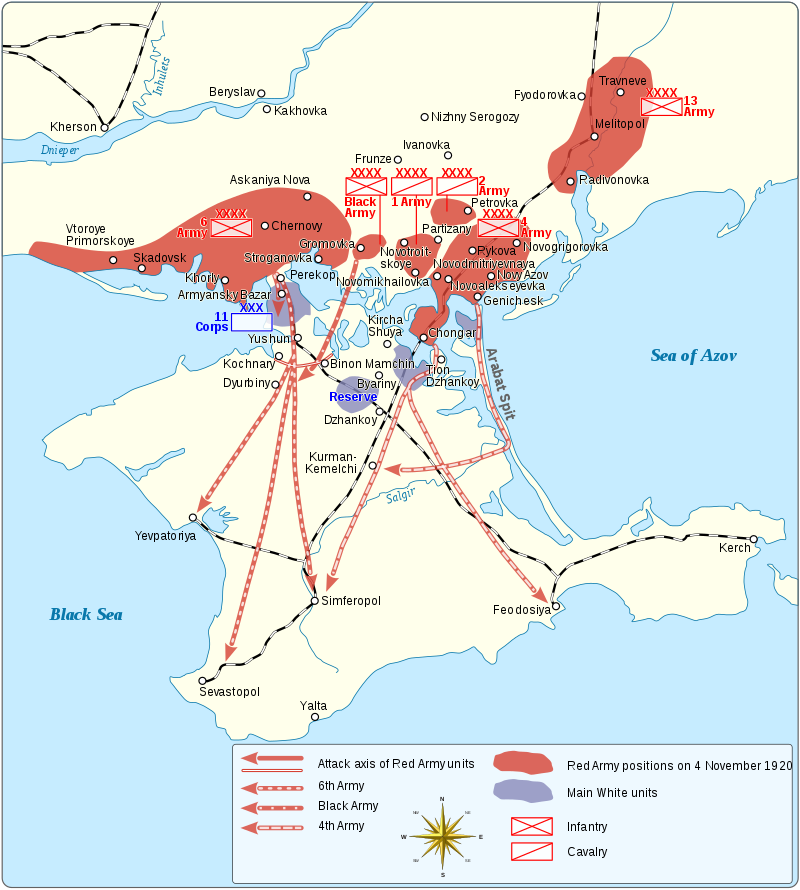

Other than from the routes overland through Perekop and the dam near it, that just leaves the four fairly small areas of roads, bridges, and an earthen dam from the north that can be easily sealed off by Ukrainian forces, and these four nodes into Crimea can likely be rendered inoperable by Ukraine without much effort. And while in the past, these routes, Perekop, and The Sivash have been used as military corridors for many centuries—including back-and-forth among Tatars fighting Cossacks or Russians and, more recently in the twentieth century, fought over between Bolshevik Reds, Whites, and Ukrainian nationalists during the Russian Civil War and between the Soviet and Nazi regimes during World War II—modern weapons and drone reconnaissance would make recreating the routes besides Perekop possibly suicidal when Ukraine is knocking on the area’s door with precision distance weapons like HIMARS, M777s, Caesars, and Storm Shadows.

The only other route into or out of Crimea is the Crimean/Kerch Strait Bridge southeast into Russia that can be rendered unusable one way or another, especially as Ukraine approaches Crimea from the north and more and more weapons systems in Ukraine’s possession come into range of hitting such a tempting target.

Russia, fearing an attack rather than being sealed off, might make the Ukrainians’ jobs easier for them as they approach from the north by destroying one or more of the four bridges aforementioned in the two locations—Chongar and Henichesk—that form the northeast routes into Crimea.

That leaves just the Isthmus of Perekop that would need to be the most heavily guarded spot, the only land entrance into Kherson Oblast that does not involve traversing something far more tenuous, hazardous, or easily destroyed.

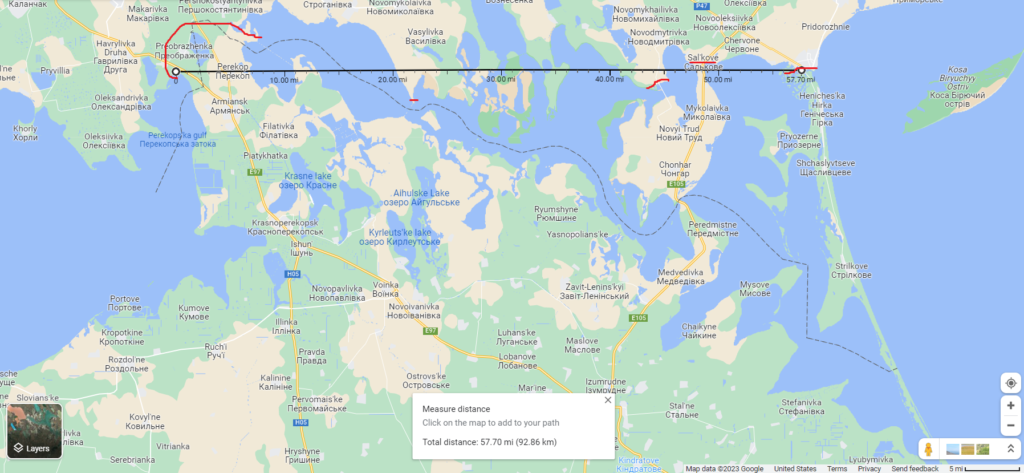

Overall, it would not be hard at all to guard against any attacks from or resupply efforts into Crimea, as the entirety of the distance from the western end of the Isthmus of Perekop to the bridge at Henichesk to the Arabat Spit is not even 58 miles in a straight line as the crow flies. Ukraine’s anti-ship missiles and air defenses have also already more or less sidelined the Russian Navy and Russian Air Force, respectively (and I discussed the naval aspect and predicted the eventual sinking of the Black Sea Fleet Flagship the Moskva just days before that historic embarrassment for Russia). With those weapons systems and others right on Crimea’s northern border, Russian air and naval forces will even easier targets, meaning there will be little Russia can do to effectively resupply Crimea from either land or sea.

III.) Sealing Off Crimea’s North and the Bigger Picture: Options

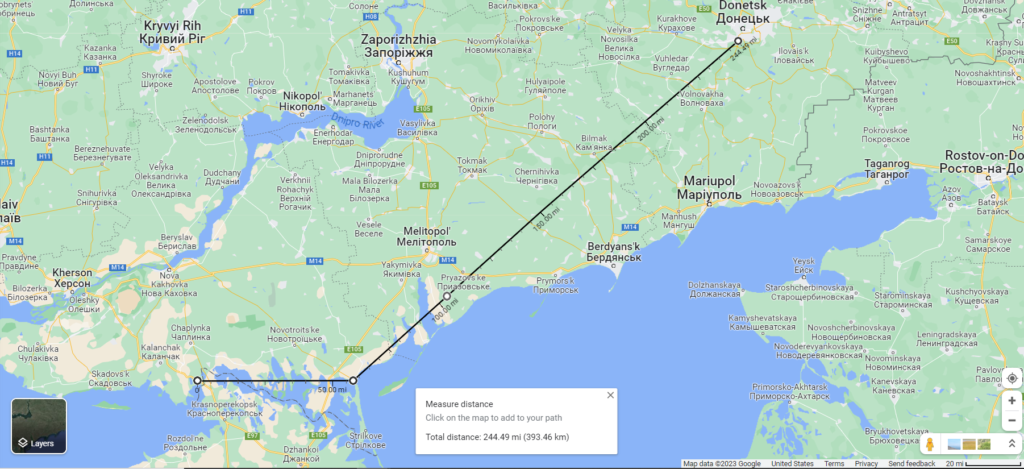

With Crimea sealed off from the north, it will be easy for Ukraine to put overwhelming pressure on Russian positions in Zaporizhzhia Oblast and Donetsk Oblast to its east. Looking ahead, Henichesk is not even 250 miles from the outskirts of Donetsk City, with mostly low-lying, hard to defend coastal plains in between, territory which has been increasingly subject to damaging Ukrainian shaping operations getting ready for Ukraine’s big counteroffensive, operations that have been going on for many, many months now and are still ongoing. Crimea itself has increasingly been subject to such shaping operations in recent months and weeks, too, including even just a few days ago. These shaping operations have been kicked into a higher gear now that Ukraine’s counteroffensive is officially underway.

Google Maps with edits from the author

It is hard to imagine Putin will just withdraw Russian troops from Crimea when they are under threat, and he will likely move to reinforce their positions from Russia via the bridge into Kerch, though such reinforcements will be of the generally inferior quality with generally inferior weapons, equipment, and leadership that has been evident with most of Russia’s reinforcements over the past year. That is because most of these troops are green and most of the best Russian equipment has been destroyed: the force that was the Russian Army on February 24, 2024, has been largely destroyed and shattered over many, many months of losing and losing badly. By the time any large numbers of reinforcements could make it to Crimea, Ukraine will be dug in on its northern border and will be able to turn the easily defended chokepoints out of Crimea into mini-Bakhmuts, graveyards for the Russian military, and even if Ukraine would have to pull back somewhat, it will still be easy to hem in Russian troops, who will be unable to hold any serious amounts of territory they might temporarily reoccupy in southern Zaporizhzhia, but it is more likely that Russia will fail to even do that and remain hemmed in inside Crimea.

As I have written repeatedly before, Crimea will begin to be a repeat of the situation from last summer and the beginning of last fall, when Ukraine, by destroying a number of key bridges, was able to box in a large number of Russian troops on the north/west bank of the Dnipro River near Kherson City; Ukraine even allowed Russia to reinforce their positions there before damaging the final bridges, allowed even more Russian troops to be trapped in a situation where they were cut off from supplies and ran out of ammunition and even food. After sustaining many casualties, the Russian survivors were humiliatingly pulled and driven out in terrible shape over pontoon bridges.

Once the northern border of Crimea has been sealed off and Ukraine dug in, setting up Crimea for a later conquest, the bulk of Ukrainian forces can continue through Zaporizhzhia, join the fight there if it is still going on so as to threaten Russian positions from the south and west even as the Russians face attacks from the north (Ukraine seems to be making impressive gains along that axis and also striking behind those lines even as I write this); things may go badly enough for the Russians in Zaporizhzhia that most of it falls before Ukrainian forces retake southern Kherson Oblast and reach Crimea—a real possibility given the issues posed by the recent man-made flooding in the area (more on that in a bit)—but regardless of whether there will still be a lot of fighting left in Zaporizhzhia Oblast at that time or not, the eventual goal for many of the troops in the area will be to move through Zaporizhzhia Oblast to join up with Ukrainian forces on the Donbas axis, perhaps even helping to outflank the main Russian line from Donetsk Oblast in the south. To focus on taking Crimea instead will mean depriving the Donbas front—the war’s bloodiest and most intense—of key Ukrainian reinforcements that could save a lot of Ukrainian lives by greatly strengthening Ukraine’s position there and decisively altering the balance of power quickly on the war’s main front, precipitating a possible collapse or at least a retreat of much of Russian’s main battle line there.

Keeping in mind our earlier principle of saving as many lives as possible while achieving your goals, the best situation will be for Ukraine with Crimea to take its time with shaping operations while the main fighting rages to the east, using its advanced weapons to soften up and destroy many targets and supplies in Crimea, which, apart from the Crimean Mountains on its southern coast, is nearly entirely exposed flat steppe plains offering little cover.

One of the main questions for Ukraine regarding Crimea, however, will be when or if to hit the Kerch Strait/Crimean Bridge to the point of rendering it inoperable (light strikes can cause more easily repairable damage while humiliating morale, causing panic among Russian colonists and sympathizers in Crimea so that they may flee to Russia). Putin funneling more troops into Crimea that will still likely be unable to break out of Crimea, let alone venture far into southern Kherson, means those troops will be unable to contribute to the fighting in the east, but he will likely do that, given Crimea’s symbolic importance and that Russia has held the region since 2014. Therefore, it might be in Ukraine’s interest to not take out the Kerch Strait/Crimean Bridge until Putin has wasted a lot of men and resources reinforcing troops in Crimea for a Ukrainian counterattack that will not come soon or for Russian counter-counterattacks very likely to fail (as mentioned, this type of approach allowed Ukraine to trap even more Russian troops on the north/west bank of the Dnipro last summer and fall).

Even if there is a decision to not take the bridge out for some time so as to allow Putin to wastefully send troops into Crimea, at some point, it will likely make sense to render the Kerch Strait/Crimean Bridge inoperable to cut off the only land supply route that would then be left for the peninsula and to do so well before any Ukrainian assaults into Crimea. Doing so in combination with precision strikes all throughout this period from Ukraine’s advanced weaponry will also greatly reduce Russia’s logistics and supplies so as to make sure Russian troops are weak, grossly undersupplied, and at their mental breaking point before any possible eventual Ukrainian assault into the peninsula.

Whatever forces Russians has in Crimea will have a hard time breaking out and being relevant in much of any way, with just a small number of key chokepoints of primary concerns for Ukrainian defenders wishing to keep those Russian forces stuck in the peninsula and irrelevant. The Russians will likely be focused on defending Crimea, anyway, although such is the stupidity of Russian command that they may very well engage in suicidal counterattacks, weakening whatever presence will be left if and when there is a Ukrainian assault into Crimea, as has been happening throughout the front lines even as Russia knew Ukraine was preparing to launch a major counteroffensive.

There will have to be some sort of balance struck between keeping the bridge open and letting Russia waste reinforcements it would send there on one hand and rendering the bridge inoperable so as to cut off supplies to all the troops in Crimea on the other. Ideally, the idea would be to keep the bridge open until Ukraine has more or less won in the east and established strong border defenses there, entrenching and creating a lethal buffer zone on the Russian side of the border and allowing it to free up some of its troops there to return to Crimea to take part in any final assault on it, with the war on Ukrainian soil likely ending there unless there is some sort of dramatic collapse of the entire Russian position in Crimea beforehand. Waiting to knock out the bridge as I have described would allow Putin to waste reinforcements there, thereby diverting troops from the east, keeping Russian force levels in the east lower than if the bridge were taken out and Russia was unable to reinforce there. This, in turns, accelerates Russia’s defeat in the east.

At the same time, destroying the bridge earlier could have a significant effect on Russian morale, both on the battlefield and among the Russian civilian population and bureaucratic officials in Russia, and could help spur more unrest, even a coup or revolution, faster.

The main point here is, after Ukraine seals off Crimea from the north, it will have multiple options to consider.

Sealed off and cut off from resupply and under constant bombardment, artillery, and missile strikes from Ukraine, if Russian forces in Crimea are watching their country get routed in the east and lose control of territory even in Russia proper—or even watching a revolution happen at home—they may even surrender or revolt en masse. Whatever they do, winning on the battlefield is their least likely outcome.

Before, I had thought it likely that Ukraine would reach the northern border of Crimea before it would have had a chance to clear out Zaporizhzhia Oblast. But now, with the historical war crime and humanitarian and ecological disaster (ecocide?) that is the recent destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and the resulting flooding of the lower Dnipro River region—and it is hard to reasonably imagine Russia is not the culprit here, with it since then destroying other dams in the area in an effort to blunt Ukraine’s counteroffensive—whenever this Siege of Crimea process could begin has inevitably been pushed back as a weaponized Mother Nature will take its course and many of Ukraine’s forces in the region will be assisting in rescue and recovery.

Still, even a flood of biblical proportions will not change the eventual outcome: Russia is already moving (has moved?) its best units in Kherson Oblast (perhaps its least-manned sector) over to neighboring Zaporizhzhia Oblast or further east, so when the floods subside and Ukraine eventually does push further south into Kherson Oblast, the Russians will be in an even worse defensive situation than they were before the flood, actually increasing the threat to Crimea.

IV: Conclusion: A Siege of Crimea Allows Ukraine to Prioritize the Donbas

Whatever direction the Ukrainian forces come from, the same Crimean geography, the same Russian deficiencies, and the same Ukrainian advantages will still exist. And all this means that it is, despite the flooding, well within Ukraine’s capabilities to seal Crimea off with a minimal number of troops and press on with the bulk of its force to the Donbas theater in the east. Such a patient approach with Crimea would bring about a much faster resolution to the far more intense and bloody combat in Ukraine’s east even while that time focusing on the east will make it easier to weaken Crimea’s sealed-off Russian defenders. Such a strategy is the most likely one to bring about the swiftest end to the war on Ukrainian soil and save the most Ukrainian lives.

That is, if Putin is not overthrown in the process and more reasonable Russians negotiate a true peace and a withdrawal of all Russian forces from all Ukrainian territory. Failing that, this might be the best strategy for winning the war available to Ukraine.

I have been wanting to go into detail on this subject and write this piece for some time, building on my earlier work, and I hope now that the reader will have come to understand why a Siege of Crimea freeing up many more troops to go fight in Ukraine’s east may be both the most likely and most reasonable course of action for Ukraine to take.

Brian’s Ukraine analysis has been praised by: Mykhailo Podolyak, a top advisor to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky; the Ukraine Territorial Defense Forces; Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, U.S. Army (Ret.), former commanding general, U.S. Army Europe; Scott Shane, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist formerly of The New York Times & Baltimore Sun (and featured in HBO’s The Wire, playing himself); Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL), one of the only Republicans to stand up to Trump and member of the January 6th Committee; and Orwell Prize-winning journalist Jenni Russell, among others. See all of Brian’s coverage of Russia’s war in Ukraine here.

© 2023 Brian E. Frydenborg all rights reserved, permission required for republication, attributed quotations welcome

Also see Brian’s eBook, A Song of Gas and Politics: How Ukraine Is at the Center of Trump-Russia, or, Ukrainegate: A “New” Phase in the Trump-Russia Saga Made from Recycled Materials, available for Amazon Kindle and Barnes & Noble Nook (preview here).

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here; because of YOU, Real Context News surpassed one million content views on January 1, 2023. Real Context News produces commissioned content for clients upon request at its discretion.

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, Threads, and Twitter. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!