Rather than signify any beginning of weaponizing foreign policy and national security in politics, the 9/11 attacks simply marked the next stage in the progression of Republicans breaking a general Cold War trend of bipartisanship and moderation when it came to the politics of such issues.

Originally published on LinkedIn Pulse September 15, 2016

By Brian E. Frydenborg (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter @bfry1981) September 15th, 2016

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

AMMAN — I’ve written repeatedly about 9/11 before: what it meant for me, what it should mean for Americans, how we have failed to properly honor the memory of the victims, how our nation has become worse, not better, since that fateful day, about all the missed opportunities. I think today it’s pretty clear that we as a nation still have not honored the memory of the victims through proper action, but what I could write about that now would be nothing new that I and others have not written before.

I’m not sure if it would make me feel better or worse to be able to write an article saying “9/11 helped to ruin us by starting a new style of politics that is ruining us.” In any case, I can’t, for while in many ways 9/11 must still clearly be regarded as a watershed, cataclysmic event in world history, let alone American politics and history, that sad truth is that the disgusting political gamesmanship of sucking in foreign policy and national security issues into the partisan maelstrom in the same manner as any other issue is not something that began (or ended) with 9/11, with the politics of 9/11 marking more continuity than change, just a larger example of growing partisanship amidst a rising tide of partisanship in post-Cold War America.

The big move towards consistent politicization in any significant way started almost exclusively with the Republican Party just a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the USSR, beginning with its withering partisan criticism of Bill Clinton’s efforts in Somalia in 1993, criticism that was wildly inconsistent and undermined U.S. policy. When Republicans began using 9/11 as a partisan wedge issue in the run-up to the Iraq invasion of 2003 and in the 2004 presidential election, this was merely a continuation of the post-Cold War modus operandi of the Republican Party, which is only more extreme today. It is worth going through some of this history to better understand this dynamic besetting America today.

Bipartisanship During the Cold War, But Not For Bill Clinton

Somalia

In 1991, Somalia’s longstanding dictator, short of international support when he was no longer “needed” after the Cold War had drawn to a close, was overthrown, and the country fell into anarchy and warlordism. The political and security situation combined with a famine into one of the first great humanitarian disasters of the post-Cold War era. With the UN Security Council supporting a relief mission, and the Democratic-led U.S. Congress, including Republicans, urging support for such a mission, Republican President George H. W. Bush, though he had just lost re-election nearly two months earlier, announced on Dec. 4th, 1992, that he would send 28,000 U.S. troops as part of a peacekeeping force intended to ensure the distribution of food to hundreds of thousands of Somalis on the verge of starvation, a move supported by President-Elect Clinton.

Not long after Clinton became president, though, Republicans especially began voicing strong criticism of Clinton’s efforts to sustain the mission, contradicting their earlier support for the mission under George H. W. Bush; while criticism was by no means coming from Republicans alone, they were generally particularly vocal and harsh in their criticism, exaggerating and distorting what was going on and using hyperbolic language to criticize a mission they were perfectly happy to support when commanded by a Republican president only a few months earlier. The mixed support of WWII veteran (and soon-to-be-Republican presidential nominee in 1996) Bob Dole was more the exception, rather than the rule, as Republicans were generally unified in opposing Clinton and succeeded in undermining public support and confidence in the mission, calling for an end to the mission and constantly threatening to cut off funding for the mission even while U.S. troops in the field were carrying it out, a mission that was far from a disaster and hardly a failure. Even when President Clinton announced a withdrawal date after the unfortunate October 1993 “black hawk down” incident, in which U.S. forces tangled with warlord forces and incurred relatively substantial casualties, many Republicans, rather than accept the withdrawal announcement as a sufficient political victory, pushed for a faster withdrawal than the one Clinton had called for; whatever Clinton did, these Republicans were sure to meet it with scorn and criticism.

In the end, hundreds of thousands of Somali lives were saved by the mission, for all its faults. But Republicans seemed to be in lock-step with Osama bin Laden as viewing the mission as an American failure (even before the “black hawk down” incident), and sure helped to move public opinion in that direction despite the significant achievements of the mission. Perhaps even more hauntingly, the experience was a major influence on Clinton’s decision not to intervene during the Rwandan genocide that occurred only months later, in the spring of 1994.

Bosnia

Clinton was already clashing with Congress over the war in the disintegrating Yugoslavia in 1993, as well, as more and more reports of Serbs committing atrocities against Bosnian Muslims dominated the headlines. It was an odd mixture of Republicans and Democrats who said the Clinton Administration was doing too little, and Republicans and Democrats who argued the Administration was doing too much. Such wide-ranging bi-partisan criticism reflected how complex and difficult the situation was in the Balkans as Europe’s first real test of the post-Cold War era unfolded; against a backdrop of confused and divided U.S. lawmakers, European governments were nervous that any aggressive U.S. action would endanger their peacekeeping forces, already on the ground in the Balkans. In other words, there were no easy solutions and no single plan had widespread, bipartisan support or even strong agreement within one party. As president, Bill Clinton was in an unwelcome and lonely position in trying to craft a position on the conflict. This situation more or less continued through 1994, though after the November midterm elections, at least the leadership of the victorious Republicans signaled a desire for more forceful action.

But somewhat conflictingly, even as Republicans seemed to want to end the arms embargo to help arm the Bosnians (unwise for multiple reasons, e.g., that escalation could have prompted Russia to arm their Serbian friends, could have weakened the NATO alliance and prompted the UK and France to withdraw their forces from the region and force America’s hand in filling the void, measures that nonetheless also had some significant support from some Democrats; still, Clinton correctly noted that “…unilaterally lifting the arms embargo will have the opposite effects of what its supporters intend. It would intensify the fighting, jeopardize diplomacy and make the outcome of the war in Bosnia an American responsibility” and increased air strikes against the Serbs. But Republicans mostly balked when Clinton publicly weighed the idea of U.S. ground forces either assisting beleaguered UN peacekeepers or helping to enforce an eventual peace; thus, Republicans slammed him for not doing enough even while slamming him for raising the possibility of what would likely help the most. They also later balked at Clinton’s efforts to help support a new UN plan to create a rapid-reaction force of European troops to help the thinly-spread peacekeeping forces already on the ground.

When a cease-fire was finally negotiated in October 1995, and the U.S. held talks in November, a more partisan nature to opposing the president came into being, just when it was most crucial to achieve peace in the Balkans for Congress to support a long-term peace plan. Nearly every Republicans in the Senate but only one Democrat sent a letter to Clinton asking him to ask Congress for approval before committing any U.S. troops to a peacekeeping force; this was done just days before formal peace talks were to begin in the U.S., undercutting the president’s team’s negotiating authority at a crucial moment. Next, nearly the entire House Republican caucus voted on a successfully-passed (non-binding) resolution that spurned and disavowed Clinton’s promise to provide 20,000 troops as part of an eventual peacekeeping force, undermining the prospects of an agreement and an end to the war, but a majority of Democrats opposed this resolution even as a substantial minority voted with the Republicans.

With negotiations between the warring parties underway on U.S. soil, House Republicans voted to prevent the deployment of U.S. troops without Congress specifically authorizing money to do so in what was largely a partisan vote, and even after the peace treaty was signed, House Republicans only narrowly failed in a bid to cut off funding for the mission (210-218) and Senate Republicans barely failed to pass a vote condemning the mission but “supporting” the troops (47-52). Another partisan vote passed just before the peace treaty was signed condemned Clinton’s decision to deploy troops, and another vote that would have offered language supporting the troops but not criticizing Clinton’s plan failed to pass pretty much along party lines the very day the treaty was signed. And in 1996, many Republicans rather myopically criticized both Clinton’s decision to provide substantial reconstruction aid for Bosnia and an extension of the peacekeeping mission. Despite Republican opposition, U.S. forces in Bosnia undoubtedly played a key and decisive role in forging and maintaining peace and stability in Bosnia and, in a larger sense, the Balkans and southeastern Europe.

Kosovo

Just a few years later, Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic was again threatening massive numbers of civilians, this time the mainly Muslim Kosovar Albanians in Serbia’s province of Kosovo. In response to a massive campaign of ethnic cleansing, NATO launched airstrikes against Serb forces threatening Kosovar Albanians. House Republicans, in particular, engaged in behavior that could reasonably (certainly) be said to have undermined the Clinton Administration’s efforts during the crisis. Not long before NATO began its airstrikes, a substantially large majority of Republicans in the Republican-dominated House voted to bar the use of American ground troops: “American soldiers have been trained to be warriors, not baby sitters,” was how House Majority Whip and Republican Tom DeLay put it. The measure was defeated by nearly every Democrat and a minority of Republicans teaming up to vote down the amendment. Even after the airstrikes began, a tie vote in the House failed to give public backing to the airstrikes. While Republican leaders tended to prevent direct challenges to the president in these cases, especially in the Senate, it was clear that many rank-and-file congressional Republicans, including a clear majority in the House, felt differently. Thus, when George W. Bush ran for president in 2000 and campaigned on pulling out of the peacekeeping efforts in the Balkans—making it clear how much value he placed on the missions in Bosnia and Kosovo—that position was not terribly surprising.

Of course, after 9/11, the Balkans receded greatly in importance in America…

9/11: More Continuity Than Change

Most people would have missed the fact that The 9/11 Commission Report, while produced ostensibly at a time when the nation was trying to heal and explicitly avoiding leveling particular blame with one administration or political party, nevertheless does make it clear how lax, unmotivated, and ill-prepared George W. Bush and his Administration were to deal with the crisis, and a careful reading (one which the general public did not even attempt or would even have been capable of attempting) showed that, while the Clinton Administration had not done everything it possibly could have done to go after bin Laden (after years of partisan Republican criticism whenever it had tried to act forcefully elsewhere!), it had increasingly focused on bin Laden as a threat over time and stridently recommended to Bush’s team during the 2000-2001 presidential transition to make bin Laden a top priority, advice which Bush’s people just as stridently refused to accept. Here is just one glaring example that exemplified both the Commission’s unwillingness to point fingers but willingness to still lay the clear picture there for those intelligent enough to follow the evidence:

“In May, President Bush announced that Vice President Cheney would himself lead an effort looking at preparations for managing a possible attack by weapons of mass destruction and at more general problems of national preparedness. The next few months were mainly spent organizing the effort and bringing an admiral from the Sixth Fleet back to Washington to manage it. The Vice President’s task force was just getting under way when the 9/11 attack occurred.” (6.5 The New Administration’s Approach)

Specifically, President Bush’s announcement that Cheney’s task force would be coming came May 8th, but presumably some thought and groundwork had occurred prior to this date. Then from May 8th until September 11th—more than four full months after Bush’s announcement—Cheney’s group had, famously, not met once; “The Vice President’s task force was just getting under way when the 9/11 attack occurred” is about as polite and diplomatic a way as possible to say that next-to-nothing had been done in those four months. One finds such an understated approach throughout the report, and an ability to look past it makes it clear a partisan gap, not in favor of senior Republican officials, in regards to the attention paid to bin Laden and al-Qaeda.

Much like after the terrorist attacks in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1983, that killed 258 Americans (among others), after 9/11 Democrats supported the Republican president—tending to give President Bush the benefit of the doubt, including then-Sen. Hillary Clinton—and conspicuously avoided playing a partisan political blame-game in the wake of a major attack against Americans even though the way both Presidents Reagan and his administration and Bush and his administration handled the events leading up to and surrounding the respective attacks in 1983 and 2001 were objectively ripe for criticism.

Of course, none of this mattered to Republicans in general, who were quick to blame 9/11 on Bill Clinton, continued to do so for years and still do so today, and who were also quick to politically weaponize foreign policy and national security as a partisan club with which to beat down Democrats into submission and defeat. Especially as debate on potential and then actual war in Iraq intensified, those who raised questions, doubts, or criticism about the decision to go to war or even how the war was being prosecuted were loudly shouted down as “unpatriotic” and/or “not supporting the troops” (I had a reputation as one of the few liberals on my small conservative college campus back in the day, and late one night at a party in 2003 one drunken Republican angrily asked me “Why do you hate the troops?”). This happened in spite of the fact that the decision to invade Iraq in 2003 and the prosecution of the Iraq war were far more deficient and problematic than the H. W. Bush/Clinton Somalia intervention and Clinton’s two Balkan interventions. Democrats also did not really intensify their opposition until it was quite clear that Iraq was going from bad to worse and the promised WMDs that were the main ostensible pretext for the invasion never materialized.

The rancor of the debate in 2002 and 2003 was just a warmup for the 2004 general election campaign between Democratic Senator John Kerry, a decorated Vietnam war veteran who was wounded twice in action, and incumbent President George W. Bush, whose stateside service in the Texas Air National Guard was largely understood as a way to keep him out of having to serve in Vietnam. A group calling itself “Swift Boat Veterans for Truth” attacked Kerry on his very Vietnam record, disputing his heroism, his accounts of what happened during his service, and his worthiness of receiving any of the medals he did receive with a bevy of shamefully false and misleading accusations, most notably displayed on prominent television ads and myopic media coverage that damaged Kerry’s candidacy greatly with various segments of the public and maybe was the greatest single factor contributing to his defeat at the hands of Bush that November. Lies, not truth, prevailed in 2004. Some of the impetus behind those attacks on Kerry had to do with the fact that Kerry, then as a recently decorated combat veteran, famously and prominently came out against the Vietnam War just after he had served in it and while that war was still very much ongoing. Even years after the election, Kerry found that he was still having to defend his reputation against those 2004 lies about his service in Vietnam. The attacks were so damaging that the term “swift boat” came to be a phrase commonly used to describe extreme and false political attacks.

This was just another chapter in the right’s attempts to both “own” national security as an issue to the exclusion of Democrats and serving up caricatures of liberals as haters-of-the-military and extremist hippies, caricatures that served as straw-man phantoms and that bore little resemblance to reality. Other recent chapters had been 1992’s and 1996’s attempts by the Republicans to portray Bill Clinton as a raging antiwar pot-smoking draft-dodging hippie unfit to be Commander-in-Chief.

Recently, It’s Just Getting Worse

Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

While the rise of Obama occurring hand-in-hand with an increasing, newly dominant anti-war feeling in America meant such fault-lines, concerns, and lines of attack would recede as they became increasingly ineffective (especially after the Obama Administration successfully took out Osama bin Laden; Mitt Romney barely mentioned, or challenged Obama on, foreign policy during the campaign homestretch in 2012), when the Arab Spring really turned for the dramatically worse and ISIS burst into view, Republicans, once again, found effective returns from investing in familiar tactics.

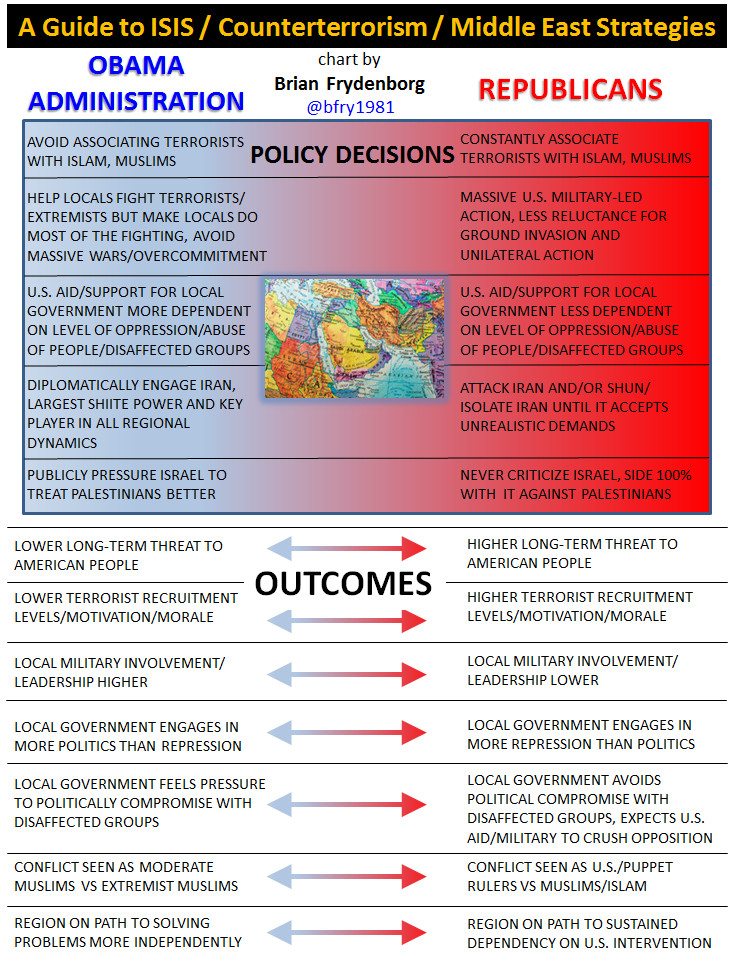

Yes, back were the days of Republicans using national security and foreign policy in hyperpartisan politicized attacks during Obama’s second term. The baseless, repeatedly-proven-to-be-false accusations trying to pin the blame on Hillary Clinton for the Benghazi attacks that killed four Americans in Benghazi, Libya—including our then-Ambassador to Libya, Chris Stevens—is perhaps the best example of this shameful disgrace of abuse of the concepts of oversight and political discourse (especially when contrasted with how Democrats responded to the 1983 Beirut and 2001 9/11 attacks, as discussed above). Other great recent examples of Republican weaponization of foreign policy and national security politics include trying to blame Obama for both the rise and success of ISIS, both accusations being quite factually incorrect, as well as pretty much the entire Republican/Trumpian critique on immigration and the despicable demonization of Obama’s and Hillary Clinton’s refugee policies (and refugees, for that matter; the previous five links are to my own detailed rebuttals of each criticism). The irony is lost on Republicans, too, as they criticize Obama both for being feckless on Syria but for doing too much on Libya, when criticism of one of those policies begs the very response of the one they are criticizing in the other, take your pick; the same can be said when they try to blame Obama for Ukraine’s crisis, even though Russia’s Putin also invaded and annexed parts of Georgia under W. Bush’s watch. The irony in their criticism is also lost on Republicans because they themselves either have terrible alternative “policies,” if they have any at all, a reality simply augmented terribly by their terrible candidate for the presidency but a reality that is very much the status quo in today’s Republican Party even without Trump.

Conclusion

Linda Davidson/The Washington Post

One thing that is certain is that the trend of Republicans hyperpartisanizing and politicizing national security issues as a party began under Clinton in the 1990s with Somalia, not with 9/11. To a very large extent, national security and foreign policy were bipartisan issues during the Cold War, but that did practice not survive after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Ancient republican (small “R!”) Roman historian Sallust hits the nail right on the head with the hammer describing this dynamic some 2,000 years ago in his Roman Republic:

“…the pattern of routine partisanship and factionalism, and, as a result, of all other vicious practices had arisen in Rome… It was the result of peace and an abundance of those things that mortals consider most important. I say this, because, before the destruction of Carthage, mutual consideration and restraint between the people and the Roman Senate characterized the government. Among the citizens, there was no struggle for glory or domination. Fear of a foreign enemy preserved good political practices. But when that fear was no longer on their minds, self-indulgence and arrogance, attitudes that prosperity loves, took over. As a result the tranquility they had longed for in difficult times proved, when they got it, to be more cruel and bitter than adversity…In this way all political life was torn apart between two parties, and the Republic, which had been our common ground, was mutilated.” ( The Jurgurthine War 41.1-5)

With the U.S., we can simply replace Rome with ourselves and Carthage with the Soviet Union, and that’s pretty much where we are today. While we faced the more-or-less existential threat of the Soviet Union, bipartisanship governed much (though hardly all) of our politics when it came to foreign policy and national security, and American victory in the Cold War was largely the result of decades of bipartisan policy and internal Soviet dynamics, hardly just because of the efforts of one man named Reagan, as many conservatives would have you believe. Since then, largely because of the Republican Party (at least until the rise of the Bernie Sanders crowd), good practices are very much on the decline, not least of all in terms of how politics and issues of both foreign policy and national security have become toxically mixed, and we can’t blame this on 9/11, for it was a disease already growing in our body politic years before.

Today, there is hardly anybody left in a Republican leadership position who is someone like Bob Dole, who, though often opposing Clinton, put American interests and productive outcomes in foreign affairs ahead of partisanship and political gain, often acting to reign in his unruly Party members. There does not seem to be any new blood among Republicans who are capable of leading and cooperating like Dole, which means this untenable status quo of today is something with which we will be stuck for some time to come.

If you appreciate Brian’s unique content, you can support him and his work by donating here.

Feel free to share and repost this article on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter (you can follow him there at @bfry1981), and here are many more articles by Brian E. Frydenborg. If you think your site or another would be a good place for this content, or would like to have Brian generate content for you, your site, or your organization, please do not hesitate to reach out to him!